The ‘total texture’ of democracy exists, and we can observe it, argues Alex Prior. This is possible through a conceptualisation of this ‘texture’ as fractal: being complex and self-referential at every scale. Through this perspective, we can problematise long-standing – but nevertheless incomplete – analogies of democracy and democratisation

'The most promising way of approaching the total texture of democracy is through words, and the publications in which they appear'. With this argument – put forward in July last year – Jean-Paul Gagnon illustrated the potential value of a ‘lexicon of democracy’. Since then, ‘total texture’, originally conceptualised by Isaiah Berlin as a complex ‘web of experiences’, has been a frequent point of reference throughout this Science of Democracy series.

It has also proved controversial, with Martyn Hammersley claiming there to be no such thing as 'a single "total texture", in the way that Jean-Paul assumes'. For many others, it has proved to be elusive, ever-changing, or even a distraction. Berlin himself conceptualised this ‘texture’ as infinitely complex and therefore essentially unobservable.

Nevertheless, I’d like to engage with this concept of ‘total texture’. I will do so more directly, more literally, than has been done so far in the series, for two reasons:

What unites both of these – from my perspective – is a conceptualisation of democratic ‘texture’ as fractal.

In the Science of Democracy series, ‘total texture’ is portrayed as a complex notion, to say the least. Leonardo Morlino argues that democracy’s ‘total texture’ has changed not only across space, but also 'in time; for example, from one decade to another'. Marcin Kaim notes that it is 'impossible to capture the total texture of democracy, which is fluid, complex, and difficult to observe in its totality.'

Invoking Berlin once again, Luke Temple observes that:

such a thick texture is inevitably: ‘of criss-crossing, constantly changing and melting conscious and unconscious beliefs and assumptions some of which it is impossible and all of which it is difficult to formulate’. This does not feel mountain-like

luke temple, Wikis and music, not mountains and butterflies

But do any of these points make a search for ‘total texture’ invalid or – dare I ask – particularly difficult? Fluidity, complexity, change (across space and time): these are common enough in the things we observe every day. I concur that the ‘total texture’ of democracy doesn’t feel mountain-like; to me, it feels fractal.

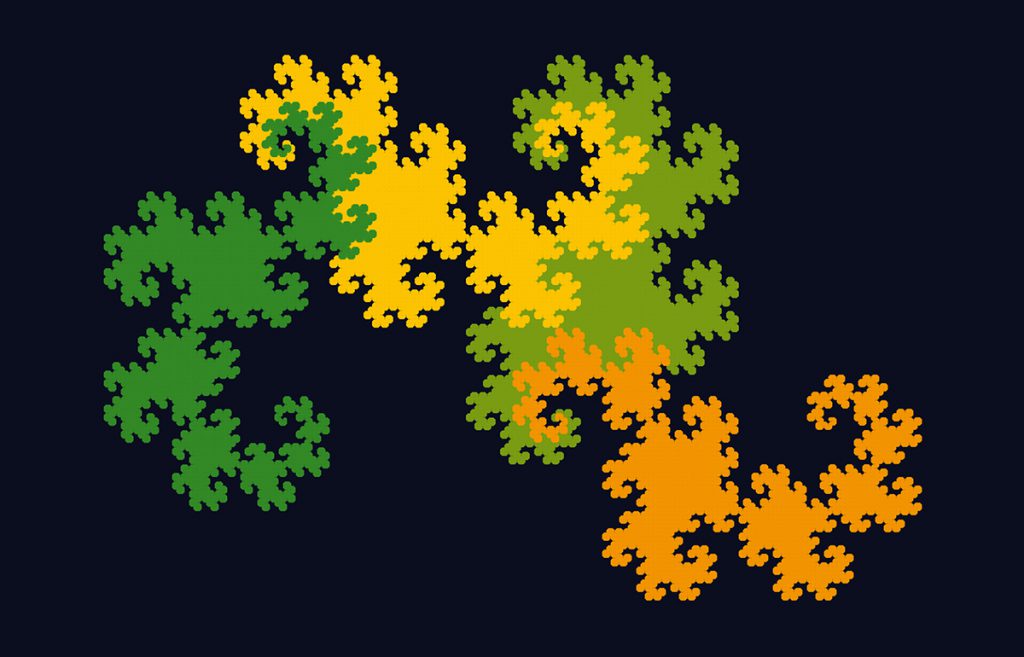

Fractals are characterised by, and composed of, repeating patterns that resemble themselves at every scale. I give an example below:

This type of fractal is called a dragon curve. It shows that even a limited range of inputs (i.e., folding either one way or another) inevitably tends toward complexity over time and across space. The crucial point here is that this complexity – the same complexity used to de-legitimise ‘total texture’ as a pursuit, even as a term – is possible, even easy, to represent.

Let us imagine the iterations of the dragon curve (i.e., each greater stage of complexity) to represent the increased complexity of democratic practice across time. In doing so, we can analogise what Lucy J Parry describes as 'the messy reality of democratic innovations'. The ‘messy reality’ is that even with limited inputs (democratic institutions, for example) we cannot count on predictable democratic outcomes.

Peter Sloterdijk’s 'pneumatic parliament', 'an imaginary inflatable outpost of Western democracy', provides a satirical illustration of this. As Sloterdijk illustrates, we cannot simply airdrop a democratic institution and expect a democratic outcome, because the institution inevitably ‘lands’ on an already established context. Fractals (like the dragon curves above) perfectly analogise the messiness of this context and its outcomes.

We cannot simply airdrop a democratic institution and expect a democratic outcome, because the institution inevitably ‘lands’ on an already established context

Discussing the ‘total texture’ of democracy as fractal is useful in its own right. However, it also allows us to cast a critical eye on other analogies of democracy and their progress. One in particular deserves our attention; we will discuss it below.

There is another blog series on The Loop that focuses on democracy. The series in question focuses on the 🌊 illiberal wave sweeping world politics. The analogy of the ‘wave’ has a long-standing appeal within these discussions. For scholars like Samuel Huntington, waves have perfectly encapsulated the surges and recessions in global democratic trends.

Appropriately enough, the icon 🌊 for the aforementioned series in The Loop is based on The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Hokusai:

I draw attention to this picture because the ‘wave’ is the wrong analogy. Below the surface (as it were), waves do not tell us much about democracy. The analogy does not hold up. Perhaps in awareness of this, Huntington shows remarkable disinclination to engage with his own analogy. Take the following question: if democratisation is a ‘wave’, what is the ‘ocean’ below it? What is the ‘moon’ that drives it?

The analogy of democratisation as a ‘wave’ is insufficient – what is the ‘ocean’ below it? What is the ‘moon’ that drives it?

You may consider these questions to be irrelevant. But the stakes could not be higher. The future of human civilisation depends on the foundations, and the drivers, of social forces. If we cannot describe them, we cannot understand them. If we cannot understand them, we cannot use them.

Democratisation, like a dragon curve, can be characterised by complex patterns that, at every scale, refer to a structural context. New parliamentary democracies constantly refer – at all ‘scales’ of decision making – to traditions of parliamentary democracy and to political context. These are structures and drivers: what might resemble a wave is a recursion, breaking away from, but nevertheless referring back to, democracy’s ‘total (fractal) texture’.

In sum, we need to rethink the way we analogise (and thereby understand) broader democratic trends. Democracy’s ‘total texture’ can be conceptualised, and it can be illustrated. In doing so, we can see how a new input interacts with a complex web of democratic experiences. Rather like weather forecasting, outcomes are finite and observable, but impossible to predict in their complexity. This is fractal logic.

No.76 in a Loop thread on the science of democracy. Look out for the 🦋 to read more in our series