By the time Italians went to the polls in September, the victory of Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party was a foregone conclusion. Dario Mazzola articulates the factors that led to the formation of the most right-wing government in the history of the Italian Republic

Since Giorgia Meloni’s victory in the Italian election, much media coverage has focused on her party’s neofascist heritage, and whether the government she has formed constitutes a threat to democracy. Yet we should not overlook the factors that produced this widely anticipated victory in the first place.

Reconstitution of a fascist party was made illegal under the 1952 Scelba law. After founding her party in 2012, Meloni defined it as ‘Christian, identitarian, patriotic’ and even ‘liberal’ in the sense of classical liberalism.

Historian Emilio Gentile, the leading authority on fascism in Italy, and the Resistance leader Giorgio Amendola, both deplored the use of the term ‘fascist’ for ideologies like Meloni’s. Most journalists and commentators agree that Meloni does not pose a fascist threat. These include Corriere della Sera’s Paolo Mieli, who is proud of his Jewish origins.

But casual statements about Italy's fascist leader Benito Mussolini in this brief French-language interview with a 19-year-old Meloni appear to contradict this view:

In her election campaign, Meloni cultivated the image of a moderate, reassuring leader. The central word in her victory speech was 'responsibility'.

Meloni appealed beyond the core base of militants to the average Italian, and managed to mobilise some previous non-voters. She vowed not to legislate on abortion and same-sex couples. She even turned contestation to her advantage; for instance, by inviting a round of applause for an LGBTQ+ militant ‘because I admire those who are ready to defend their ideals'. The activist later thanked her publicly on social media.

Meloni opposed Draghi’s government, but did not adopt an anti-establishment stance. Ultimately, she disappointed both Russophiles and anti-vaxxers. Commentators even speculated she could have formed a government with Democratic Party leader Enrico Letta, or a pact with Mario Draghi. She vocally denied both scenarios, but the mutual respect between Meloni, Draghi, and Letta was clear.

An energetic leader, Meloni avoided the trap of engaging in personal insults. She was all too aware the public response would be unfavourable. After all, a politician like Berlusconi had been exploiting his adversaries’ contempt for decades. ‘Poor they: they are haters, unable to love,’ he used to retort, while smiling, shaking hands, and telling jokes. We couldn't say that about Meloni.

At 45, Meloni was the youngest candidate in the Italian election. Indeed, she had been Italy's youngest minister in the 2008–11 Berlusconi government. Yet after Japan, Italy is the nation with the largest proportion of elderly people. Political renewal and change are thus difficult to achieve, although many Italians aspire to them. The Brothers of Italy party was relatively new and untested, and had never participated in government. Meloni was therefore a novelty.

Former Foreign Minister and Italian ambassador to Israel and the US, Giulio Terzi Sant’Agata, helped Meloni develop a more reassuring image abroad. This included delivering addresses and interviews in English on CPAC 2022 and Fox News, and becoming the leader of the Eurosceptic, anti-federalist European Conservatives and Reformists group.

Atlanticism was also decisive. Unlike Salvini and Berlusconi (‘Putin’s best friend’), Meloni never suggested compromising with Russia after the Ukraine invasion. She also delivered an exclusive interview to the Taiwan Central News Agency laying out her thoughts on Italy's relationship with Taiwan. The Chinese government's first tweet after Meloni's victory, meanwhile, recommended a ‘pragmatic China policy’.

The Brothers of Italy is one of the few parties that, by staying in opposition, managed to avoid the twists and turns in strategy and tactics that have characterised other Italian parties including the League, Five Star and the Democratic Party. Throughout the campaign, Meloni’s position appeared more linear and predictable than those of the other parties.

Social media tends to reward young, creative leaders. In an age dominated by such media, television tycoon Berlusconi was doomed to lose influence. On Facebook and Instagram, Meloni showcased her personality above her politics, helping voters relate to her, and feel reassured. Often alongside Meloni on her electoral campaign were her young daughter Ginevra, and partner Andrea Giambruno, a journalist.

Finally, what condemned the centrist and leftist parties to failure was their division. Even before their electoral defeat, some Democratic Party representatives had already turned on leader Enrico Letta. In contrast, the quarrelsome right-wing coalition managed to retain a semblance of unity during the campaign, while Meloni’s party gave her its consistent support.

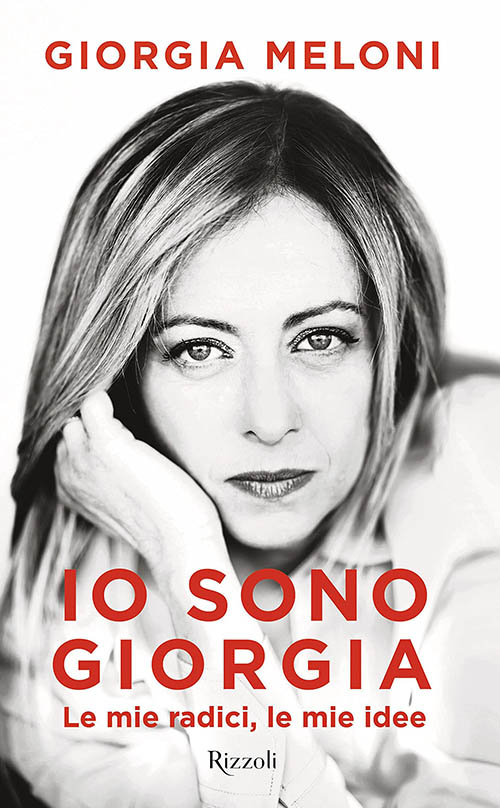

Raised by a single mother, Meloni, too, is an unmarried parent. Her political refrain 'I am Giorgia, I am a woman…' matches the title of her autobiography I Am Giorgia. In putting her persona up front, she has emphasised her gender. Meloni has declared in the past that being both female and short, she needs to shout to be respected. She has often rejected attacks against her as misogynous. In return, Meloni has elicited expressions of solidarity – even from leaders of the left.

Meloni’s bestselling autobiography: I am Giorgia: My Roots, My Ideas is packed with inspirational quotes from celebrities and pop musicians, including Ed Sheeran. In the book, the author focuses more on her private circle of 'little women' than she does her political ideologies

In the decade since 2013, the Italian electorate has shown enormous volatility. Vote share has shifted wildly between Renzi’s Democratic Party, the Five Star Movement, the League and now the Brothers of Italy. The leaders and former leaders of these parties – Matteo Renzi, Matteo Salvini, Luigi di Maio and Giorgia Meloni – may differ ideologically. However, they are relatively young, they engage in populist rhetoric and policies and, crucially, they all promise change.

The Italian electorate is experimenting with one proposal after another. And the proportion of non-voters in Italy continues to grow. Major parties retain a consistent 5–10% bedrock of the vote share. Yet some 20–30% of politically active Italian voters change their preferences from one election to another. In this latest Italian election, Meloni was the beneficiary of voters' willingness to change their minds.

Even if there were deeper factors at work (Anthony J. Constantini, for example, links Italy’s national dynamic to the supranational populist trend), the abovementioned factors combined to facilitate Meloni’s victory. However, winning an election is one thing, governing successfully quite another.

Significant challenges confront Italy's new government. In the months and years ahead, these challenges will be a true test of the new Prime Minister’s credentials and skills.