A second term of office for Emmanuel Macron remains the most probable outcome of the French presidential election, but it is no longer a foregone conclusion. The race with Marine Le Pen now looks more competitive than ever, says Giovanni Capoccia

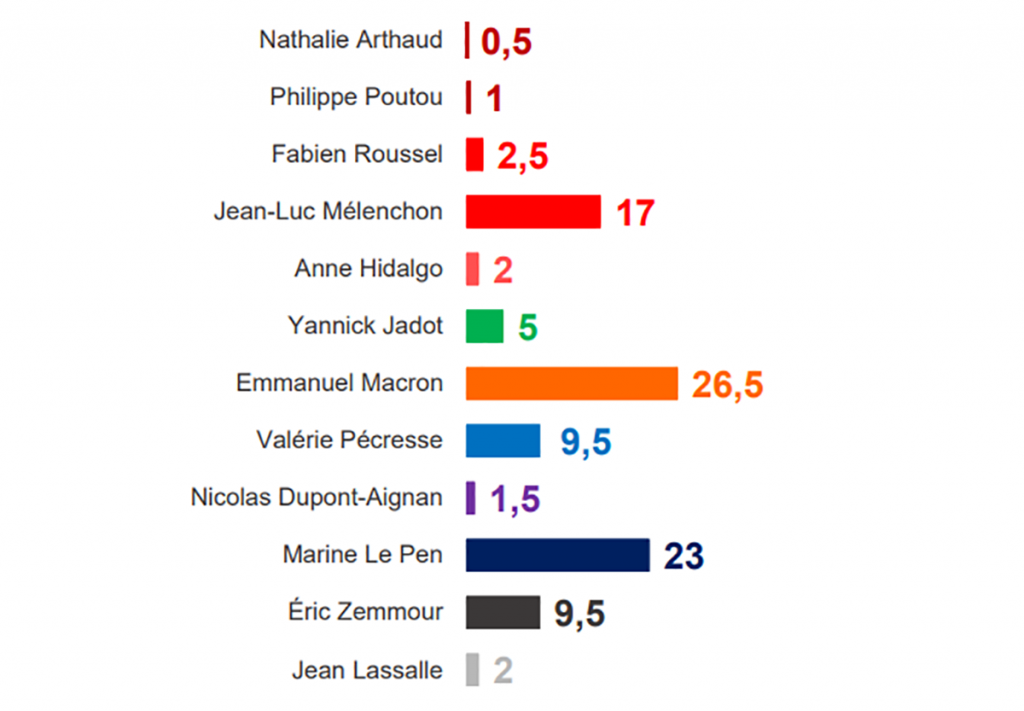

The first round of the French presidential elections is only a few days away. Incumbent Emmanuel Macron (La République en Marche) continues to lead the polls with 26.5% of the vote, followed by Marine Le Pen (Rassemblement National) at 23% and with Jean-Luc Mélenchon (La France Insoumise) in third place at 17%.

All the other candidates look to be out of the race. Even those once regarded as possible contenders, in particular Éric Zemmour (Reconquête) and Valérie Pécresse (Les Républicains), trail at less than 10%. They have little chance of qualifying for the second round.

Last autumn, many considered a repeat of the 2017 Macron-Le Pen duel in the second round the most likely scenario. The implication, supported by the polls, was that the French President would again defeat the Rassemblement National candidate with ease. But the situation that has emerged after a six-month campaign is quite different. The gap between the two candidates has narrowed significantly. A Macron victory, although still the more likely outcome, is no longer a foregone conclusion.

The invasion of Ukraine initially appeared to bolster Macron’s chances of an easy victory. Macron has been able to cast himself as a 'war President', rallying support for Ukraine while at the same time engaging in peace diplomacy. This had a strong positive effect on Macron's polling figures, and damaged support in the polls for Le Pen, Mélenchon, and Zemmour. All three have, in the recent past, expressed positive views of Vladimir Putin.

The Ukraine effect, however, is beginning to fade. Strategic voting now seems to be taking its place. Rather than vote for their preferred candidate, voters seem inclined to settle for the 'least worst' option, if that candidate looks likelier to win.

Strategic voting has likely contributed to the improvement in poll numbers for Le Pen and Mélenchon over the past 10–14 days. Le Pen has probably attracted many who would otherwise have voted for Zemmour, whose numbers have dropped considerably. This tendency is likely to increase as Mélenchon rises in the polls. Many Zemmour supporters (and some Pécresse supporters, too) would rather cast a vote for Le Pen than face a second round between Macron and Mélenchon.

Yet a renewed Macron-Le Pen duel is not likely to be a mere repeat of 2017. With the growth of the extreme right, Zemmour supporters constitute a large potential reservoir of votes for Le Pen. Zemmour has been the great surprise of this campaign; at one point, there was a real possibility he might reach the second round. Zemmour's radical language, along with his background as a non-professional politician, have attracted many who might otherwise have not bothered voting. At the same time, he makes Le Pen look less extreme.

Le Pen has focused her campaign on socioeconomic themes, in particular on 'purchasing power'. This has been the main preoccupation of voters throughout the campaign. At the same time, she remains a credible choice for people concerned about immigration and security, the main themes of Zemmour's campaign. Polls show that nearly 80% of Zemmour's current supporters would vote for Le Pen in the second round.

In 2002, when Marine Le Pen’s father, Jean-Marie, unexpectedly qualified for the second round of that year’s presidential election, the leaders of almost all other parties united against him. They encouraged the electorate to support instead Le Pen's mainstream rival, incumbent President Jacques Chirac, to prevent the Front National (a predecessor of the Rassemblement National) from winning the Presidency.

However, this logic of 'blocking the extreme right at all costs' wouldn't work so effectively today. It remains likely that leaders of some smaller parties, particularly on the left, will invite their supporters to vote Macron. But the same cannot be said of the larger parties excluded from the second round.

The logic of 'blocking the extreme right at all costs' is much weaker today than it was in 2002

Mainstream right party Les Républicains are divided. Their candidate Valérie Pécresse’s main competition in the primaries last December was Eric Ciotti, supported by about 40% of the party. Ciotti has explicitly expressed his aversion for Macron, for whom he pointedly did not vote in 2017.

Similarly, Mélenchon's party La France Insoumise advocates that 'no vote should go to the extreme right'. Yet it will not encourage its supporters to vote for Macron against Le Pen. Thus, they will likely be free to choose. Polls show that a slightly higher percentage of Mélenchon supporters would vote for Le Pen than for Macron (31% vs. 28%), and most of them (41%) would abstain.

The French electorate is polarised between three ideologically distant political camps – the extreme right (Le Pen/Zemmour), the centre (Macron), and the extreme left (Mélenchon). This is likely to lead to a higher-than-usual abstention rate in the second round.

Very few are likely to transfer their vote among the three camps of the polarised French electorate

By admitting only the top two candidates in the second round, the French electoral system shoehorns this three-way competition into a two-way logic. Le Pen, Macron and Mélenchon are all likely to attract votes from smaller parties within their respective political camps. However, vote transfer between camps is likely to be limited. Hence, abstentions, expected to reach 30% (high for French presidential elections), are likely to play a disproportionate role. The second round will, therefore, be harder to call.

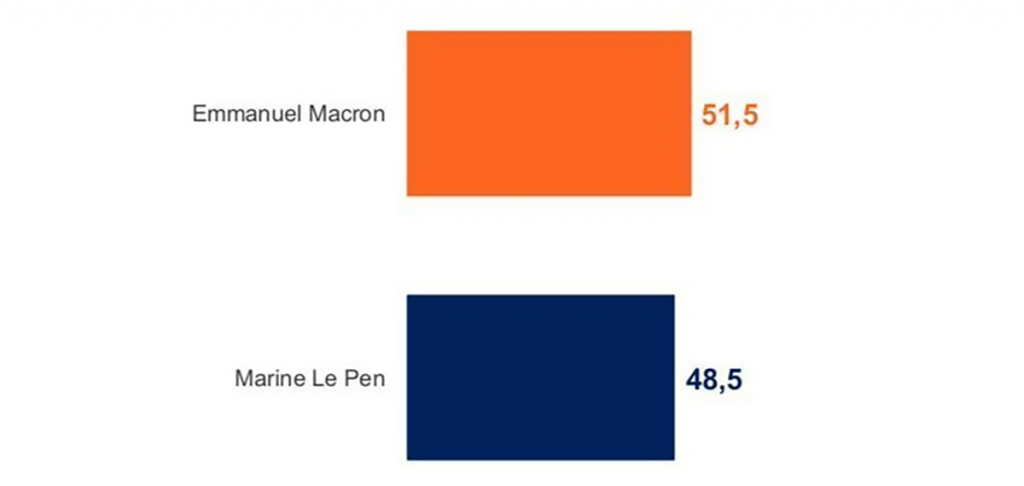

The latest polls credit Macron with a narrow lead of 51.5% against 48.5% for Le Pen. This is within statistical error. Back in September, the distance between the two candidates was 15–20%. Second-round polls fielded before the first round has taken place are often unreliable. However, it seems clear that Macron, against all expectations, will have to make considerable effort to mobilise voters between now and 24 April if he is to win a second term. Even Macron’s ex-Prime Minister Édouard Philippe recently issued the stark warning: 'Marine Le Pen can win this election'.

Thank you for sharing your analysis. It seems this election will probably be decided by two elements:

1) How quickly will the inflation escalate between 1st and 2nd rounds?

1) Whom will Melechon's voters align with in the second round? Given the high expected abstention rate, if 1/3 of Melechon's supporters turn to support Le Pen, they may push her to victory.