We know that voters stereotype Muslim politicians as homophobic. However, voters also project their own ideas about LGBTQ+ rights onto politicians. Sanne van Oosten examines which of these voter tendencies are likely to prevail with which voters, and argues that both strength and type of opinion matter

People's opinions about LGBTQ+ rights are becoming more important in how they see themselves and their societies. At the same time, some use LGBTQ+ rights as a way to criticise and attack other cultures, especially Muslims. Jasbir Puar calls this phenomenon 'homonationalism'.

In this climate, political party gatekeepers struggle with inclusion of Muslims in political parties because they fear criticism from voters. In a recently published article I examine which voters tend to stereotype Muslim politicians as homophobic.

Academics have written countless books and articles on the concept of homonationalism. This tactic uses LGBTQ+ rights to promote nationalist agendas and create divisions between western societies and 'others', particularly Muslim-majority countries. Nationalist political actors invoke LGBTQ+ rights to portray the West as progressive and civilised. They contrast this with societies which are regressive and uncivilised. Homonationalism is a powerful narrative, in particular because criticising it can be interpreted as betraying LGBTQ+ rights.

Homonationalism is a powerful narrative, especially because criticising it can be interpreted as betraying LGBTQ+ rights

Homonationalism also plays a significant role in discussions about diversity in politics. Members of selection committees, particularly those of left-wing political parties, often struggle with the inclusion of Muslims on their party's list. They fear that voters with an egalitarian worldview will stereotype Muslims as homophobic.

But is that the case? Do voters actually do this? Or are voters inclined to project their own ideas onto politicians, regardless of whether they are Muslim or non-religious?

I investigated these questions by looking at voters in France, Germany, and the Netherlands. The Netherlands was one of the first countries where LGBTQ+ rights became part of the national identity. Others followed, including France and Germany.

I presented a sample of over 3,000 respondents with experimental profiles of fictional politicians. The religion, gender, and migration background of these politicians varied. I asked respondents whether they expected the politician presented to be in favour of or against adoption by same-sex couples.

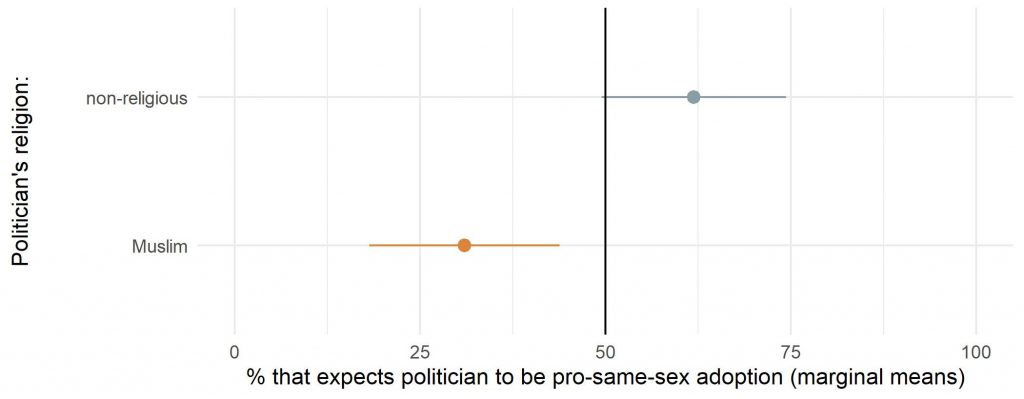

The findings show that voters do indeed stereotype Muslim politicians as homophobic, as depicted in the figure below. Only 31% of the voters expect Muslim politicians to support LGBTQ+ rights regarding adoption. This is significantly lower than expectations for non-religious politicians.

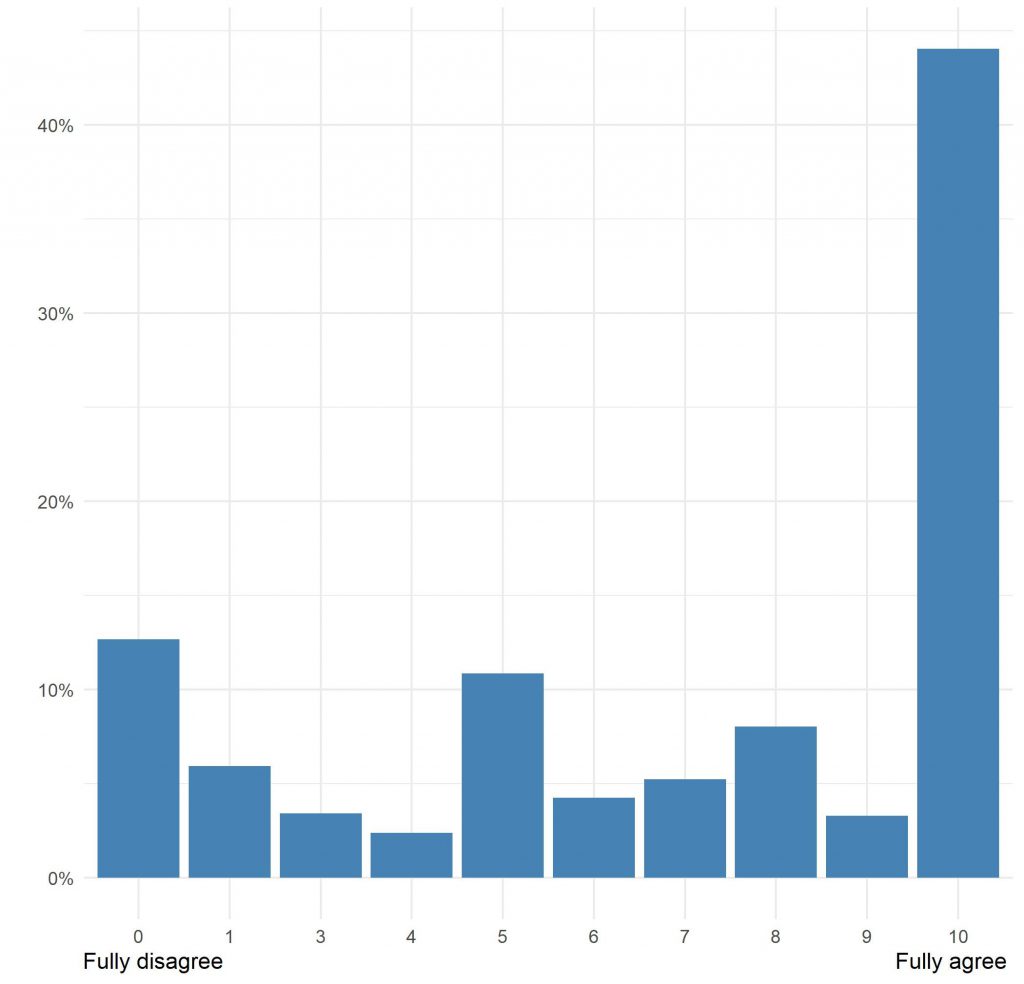

I also asked respondents to report their view on adoption by same-sex couples on a scale of 0 to 10. The bar chart below shows that 44% of the respondents fully agree with it. Meanwhile, 13% of the respondents strongly disagree, answering 0. I refer to those who answered either 0 or 10 as 'flankers'. The remaining respondents provided answers between 1 and 9, and I refer to them as 'moderates'. As a result, I divided the respondents into anti-flankers, moderates, and pro-flankers.

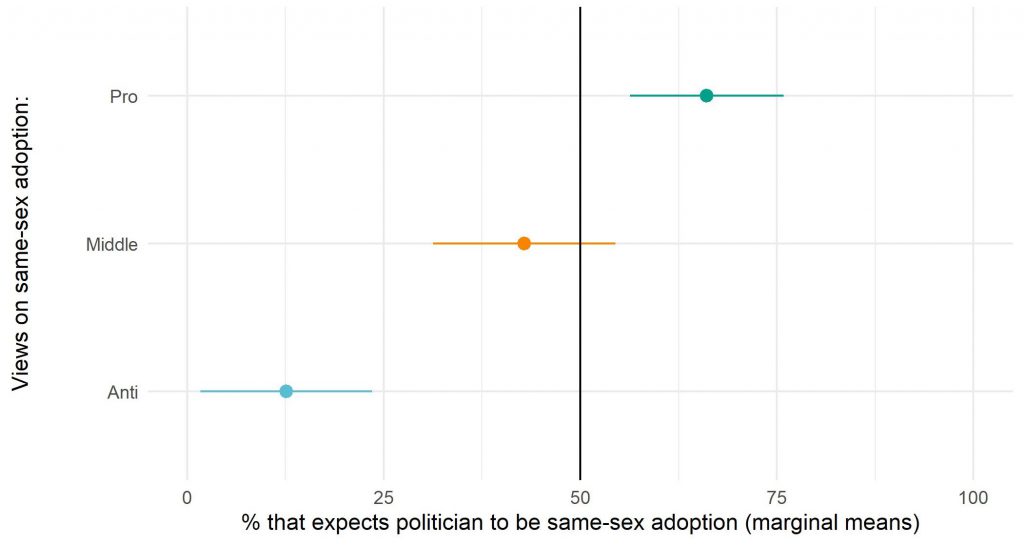

Then I examined whether voters project their own ideas onto politicians, regardless of the politicians' religious affiliation. In the figure below it becomes clear that voters also project their own ideas about LGBTQ+ rights onto politicians.

Anti-flankers expect politicians to be in favour of LGBTQ+ rights significantly less than half of the time, while pro-flankers expect politicians to be in favour of LGBTQ+ rights significantly more often. Moderates fall in-between.

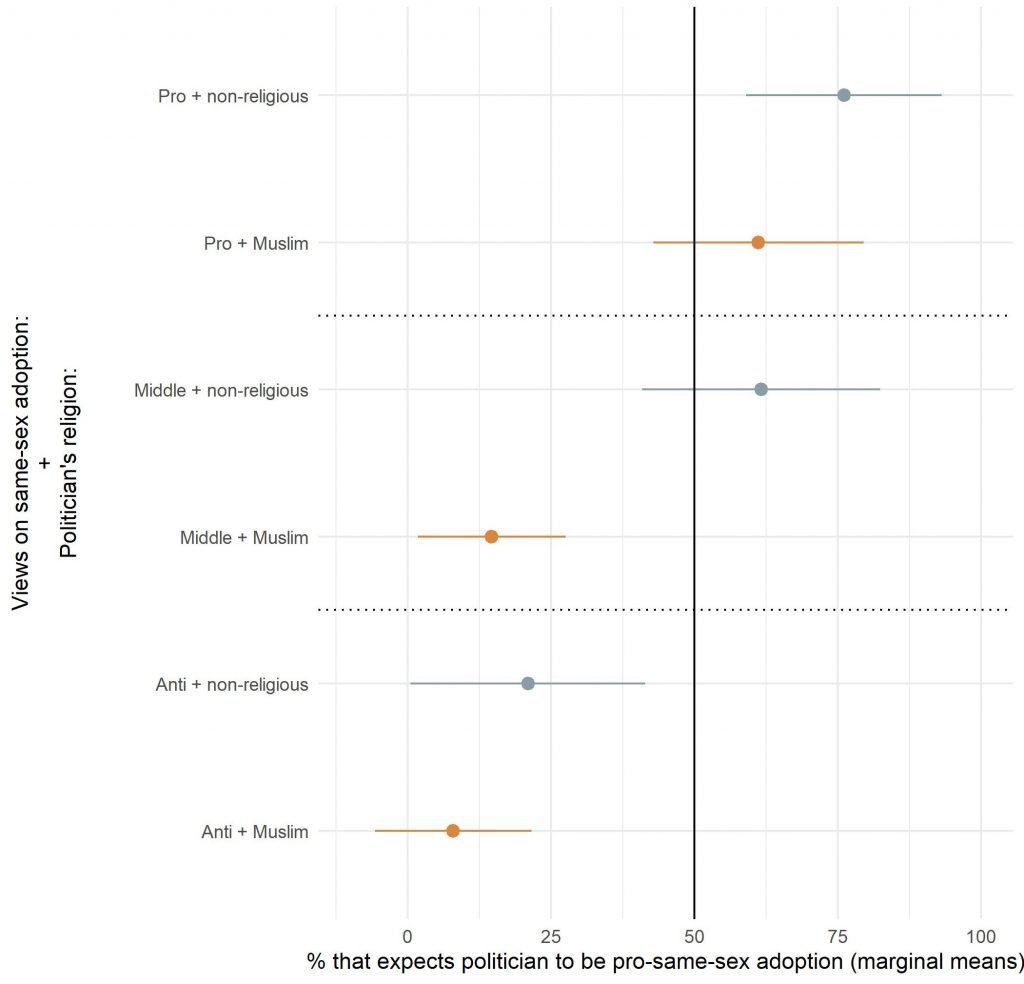

We now know that voters both stereotype and project their own ideas. But which factor is more important: stereotyping or projection? I demonstrate this in the figure below, examining how flankers and moderates perceive Muslim politicians within each group.

Pro-flankers and anti-flankers do not have significantly different expectations of Muslim politicians versus their expectations of non-religious politicians. Therefore, they do not stereotype Muslim politicians. Instead, they project their own ideas onto politicians, regardless of whether they are Muslim or non-religious.

On the other hand, moderates do have significantly different expectations of Muslim and non-religious politicians.

Flankers tend to project their own ideas, while moderates engage in stereotyping. Specifically, it is voters with lukewarm feelings about LGBTQ+ rights who tend to stereotype Muslims as homophobic. Meanwhile, the largest group of voters does not stereotype Muslims as such. Why is this so?

It appears to be related to their perceived distance from Muslims. The voters who are most supportive of LGBTQ+ rights also feel the least different from Muslims. The less they perceive themselves as being different from Muslims, the more inclined they are to project their own ideas about LGBTQ+ rights onto Muslim politicians.

Voters with lukewarm feelings about LGBTQ+ rights are inclined to stereotype Muslims as homophobic, while voters with strong feelings about LGBTQ+ rights are not inclined to do so. But those who emphasise LGBTQ+ rights in discussions about Muslims may not necessarily be the ones who are most supportive of LGBTQ+ individuals. They may instead be those who have stronger negative attitudes towards Muslims.

Those who emphasise LGBTQ+ rights in discussions about Muslims may in fact be those who have stronger negative attitudes towards Muslims

In a situation where homonationalist and populist/radical-right ideas are prevalent, people in charge of political parties believe that voters have negative views of Muslims based on stereotypes. However, the findings of this study show that isn't always true. While there is often discursive backlash against Muslim politicians, this doesn't always result in electoral backlash. Political parties that promote equality will gain electoral advantages by including Muslim politicians and strongly countering homonationalist ideas.

I think that muslims and ortodox jews are most hateful religious groups toward homosexuals. In vast majority they deny people born nonhetero basic rights to marriage in civil registry which discrimination is awful. Jews and muslims demands acceptation and priviledges for their views but their often hard discriminate people born lgb, christians and women.

It is not a stereotype but a reality. For example, Labour MPs Zarah Sultana and Apsana Begum in the UK abstained from votes supporting LGBTQ-inclusive education. In Canada, Liberal MP Salma Zahid initially opposed aspects of LGBTQ curriculum in Ontario schools. In France, some Muslim local politicians have voiced opposition to pride parades or LGBTQ education initiatives. The First Minister of Scotland, Humza Yousa, in February 2014, during the final Stage 3 vote on the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2014—which legalized same-sex marriage was notably absent and did not cast a vote. Islamic homophobia is an existential threat to LGBT community.