James F. Downes argues that elections to the European Parliament will likely lead to record representation for populist far-right parties. Lack of unity and ideological divisions, however, will make it difficult for them to wield any real power

Elections for the European Parliament (EP) in June 2024 could be the most important in EU history. The EP has legislative, budgetary and supervisory powers. No EU laws can be passed without the approval of Parliament, which also acts as a check on the EU Commission, currently led by Ursula von der Leyen. So, EP election outcomes matter.

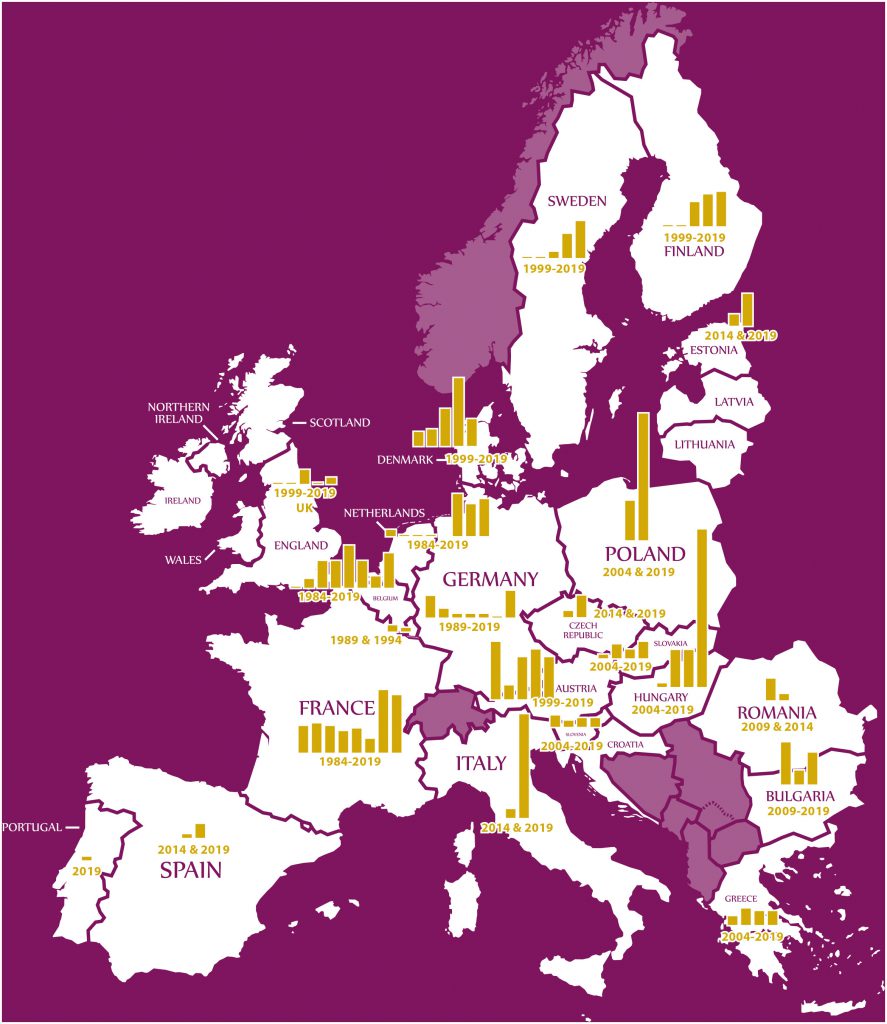

As the map below shows, in the last two EP elections, far-right and Eurosceptic parties significantly increased their vote and seat shares.

If current opinion polling forecasts are correct, this trend will continue in the 2024 elections. Far-right parties are expected to make considerable gains in countries including Austria, Belgium, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Slovenia. As the table below shows, this will result in an even larger number of Eurosceptic far-right parties enjoying EP representation.

Far-right parties are expected to make considerable gains in Austria, Belgium, France, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland and Slovenia

There are two main far-right party blocs: ID and ECR. The ID group is projected to gain 27 additional seats; ECR a further four. Predictions are that support for established centre-right parties will decline. The centre-right European People's Party (EPP), for example, is projected to lose seats. A more modest gain of two seats is expected for the centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D).

Though the EPP would still probably be the largest party grouping inside the EP, it remains likely to face difficulties in getting its policies through during the next Parliament.

| Party grouping | Ideology | Current number of seats held | Projected number of seats, according to Politico |

| European People's Party (EPP) | centre right | 178 | 175 |

| Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) | centre left | 141 | 143 |

| Renew Europe (RE) | centre | 101 | 83 |

| Greens/European Free Alliance (EFA) | centre left | 71 | 41 |

| European Conservatives & Reformists (ECR) | centre right and far right | 67 | 71 |

| Identity & Democracy (ID) | far right | 57* | 84* |

| The Left (GUE/NGL) | far left | 38 | 32 |

| Non-Attached (NI) | n/a | 52 | 41 |

| New Unaffiliated (NU) | n/a | n/a | 50 |

While mainstream parties have their own challenges, the main obstacle for the populist far right in the EP is that no single ideological bloc is acting together.

Instead, the far right is split into two main ideological groups. The ECR grouping includes national conservative and far-right parties such as Poland’s Law and Justice Party and Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d'Italia. This grouping, the fifth-largest in the EP, with representation from 17 countries, currently holds 67 of the 705 seats.

The main obstacle for the populist far right in the EP is that no single ideological bloc is acting together

The newer ID ideological grouping was founded in 2014. It features a wide range of populist far-right parties, including Rassemblement National of France, Italy’s Lega, and Geert Wilders' Freedom Party, the biggest party in the November 2023 Dutch national parliamentary elections. ID, the sixth-largest grouping in the EP, with representation from nine countries, currently holds 57 EP seats.

Exacerbating the fragmentation of the far right in the EP is the fact that prominent far-right parties such as Hungary's Fidesz, which currently holds 12 seats, are non-inscrits or non-attached members.

Far-right parties tend to be united in supporting tougher border restrictions and anti-immigration policies. Yet the ECR/ID division is visible in other policy areas.

First, the two ideological blocs are divided over whether to remain in the EU. Some far-right actors are Eurosceptic reformists; others support outright withdrawal from the EU.

Some far-right actors are Eurosceptic reformists; others support outright withdrawal from the EU

Rassemblement National used to advocate for leaving the EU. In recent years, however, in a bid for broader appeal, Marine Le Pen’s party has changed its tune. In the Netherlands, the Freedom Party is adopting a similar strategy. Fratelli d'Italia and the Hungarian party Fidesz, too, both now believe they can reform the EU from the inside. Their parties emphasise national sovereignty and oppose further EU integration or centralisation of power. Germany's Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and the Freedom Party of Austria, by contrast, still seek a hard Brexit-style EU withdrawal.

Second, there are differences on foreign policy issues. For example, some far-right leaders, including Hungary's Viktor Orbán, are sympathetic towards Russia and Vladimir Putin. Others, such as Giorgia Meloni, have condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Third, tensions recently emerged between Rassemblement National and AfD, after some AfD members discussed the 'remigration' of foreign-born Germans. This angered Marine Le Pen because it went against her continued efforts to de-radicalise and mainstream her party’s image.

Most significantly, the ID group in the European Parliament recently expelled AfD, accusing the party of ideological extremism and connections to China and Russia.

Some on the left fear that climate change-denying populist far-right parties could kill off Commission President Von der Leyen’s Green New Deal in the new parliament. My analysis suggests the risk is not so great. The far right is ideologically divided, and lacking in unity. Even if it manages to increase its EP representation substantially, it is unlikely to trigger a political earthquake.

The populist far right may well emerge stronger after these elections. Deep-seated divisions, however, will make it extremely difficult for it to wield any real influence.

Derived from a Special Guest Lecture delivered by the author for the University of Hong Kong (HKU) 2024 MOOC, Europe Without Borders