The fight against corruption has been at the heart of recent mass protests across the world. But does corruption drive political participation, and if so, who is it mobilising? Research by Martín Portos and Raffaele Bazurli suggests – counterintuitively – that people with less education are the most likely to rise up

The moral redemption of power is a common aspiration for many social movements of the modern era. Exactly ten years ago the 15M / Indignados began occupying city squares throughout Spain, shaking up domestic politics. As the manifesto of its organising platform Democracia Real, ¡YA! put it:

Some of us consider ourselves progressive, others conservative. Some of us are believers, some not. Some of us have clearly defined ideologies, others are apolitical, but we are all concerned and angry about the political, economic, and social outlook which we see around us: corruption among politicians, businessmen, bankers, leaving us helpless, without a voice.

In the face of the crisis of neoliberalism, progressive social movements have expanded the notion of corruption. Such movements frame it as a broader crisis of democratic legitimacy driven by collusion between public and private interests.

However, demands for ‘clean governments’ are not the exclusive preserve of left-wing milieus. Anti-corruption protests, for example, have been crucial to undermining the hegemony of the Brazilian left. In 2018, such protests also helped secure electoral victory for the far-right populist Jair Bolsonaro.

Political elites are targeted for occupying and using state power in their own interest. Thus, they reveal a growing inability and unwillingness to respond to popular demands.

Citizens can voice discontent about corruption — and seek to mitigate it — by taking part in anti-corruption campaigns and social movements more broadly. Scholars of corruption, as well as some recent ongoing initiatives, stress the ability of citizens, movements, and the media to fight corruption from below through collective action.

scholars stress citizens' ability to fight corruption from below, through collective action

Yet the association between belief in extensive corruption and broader non-electoral participation has received little attention. Empirical evidence, too, is inconclusive. So when citizens in a polity believe corruption is widespread, we do not know how far this deters or invites political mobilisation outside the polling station.

Our recent International Political Science Review article draws on the International Social Survey Programme’s Citizenship 2014 module. This module contains empirical evidence from 34 countries across the world. Our research studies the nexus between belief in extensive corruption, and non-electoral participation.

We understand non-electoral participation as engagement in political behaviour other than voting. Our scale measures information on prior records of involvement in several political repertoires of action. These include signing a petition, participating in a boycott, attending a political meeting or rally, contacting a politician, contacting the media, and donating money or raising funds for a political cause. We came to three conclusions:

Corruption (or, rather, believing corruption is widespread) does fuel political participation. We show that people tend to engage more in non-electoral mobilisation when they think institutions are controlled by vested interests.

Electoral studies have shown that corruption has a 'dispiriting effect' on potential voters. These voters are thus more likely to stay at home on election day. Sometimes, conventional channels of mobilisation are not credible in the eyes of citizens. In such instances, citizens may embrace contentious politics to express political discontent.

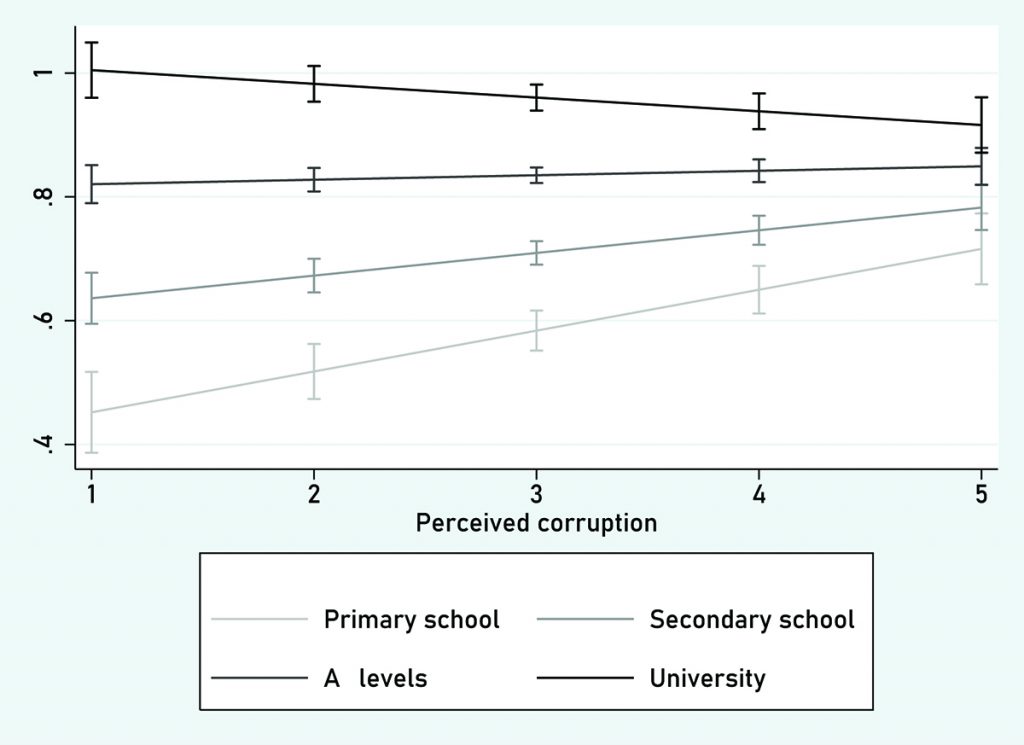

The extent to which non-electoral participation is influenced by the perception of extensive corruption is uneven across the population. The association between perceiving widespread corruption and non-electoral political participation is not purely additive. Rather, it is contingent upon factors related to the individual’s political interest and education.

Theories of societal accountability posit that the most educated and politically interested citizens are the societal driving force against corruption. We find, however, that perceiving endemic corruption is likely to breed resignation — rather than indignation — across this section of the population.

Conversely, identifying widespread corruption is likely to foster moral outrage among citizens who are less educated and have less interest in politics. These citizens are thus keener to embrace anti-elitist arguments and, ultimately, to engage in extra-institutional behaviour.

So, are politically sophisticated citizens really spearheading the battle against corruption? The findings above suggest that this is more a normative assumption than data based on empirical evidence.

Corruption, then, matters for non-electoral participation, but not in the way often assumed. Believing that corruption is widespread leads to resignation rather than indignation among the most educated and politically interested citizens. Those who are less educated and politically interested are more likely to take to the streets when they think the system is rigged.

Those who are less educated and politically interested are more likely to take to the streets when they think the system is rigged

This result echoes studies on the ‘demand side’ of populism. These studies find that populist attitudes (and anti-elitism as one of their defining components) can reduce education-based gaps, and even reverse income-based inequalities in political participation.

Our findings are not important only for scholars of political behaviour, who should incorporate perceived corruption into their theoretical and empirical models.

The findings also have implications for anti-corruption campaigners and policy-makers, who must appeal to less sophisticated citizens if they want to ensure their demands are met.