President Jair Bolsonaro faces criticism from the media and civil society for his disastrous response to the pandemic. Reviving National Security Law to intimidate his critics is more than a nod to Brazil's authoritarian past, writes Eduardo Burkle

Victory for Bolsonaro in the 2018 election marked another chapter in the success for far-right populists over the past decade. A former member of the armed forces, Bolsonaro famously praised the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil with violence from 1964 to 1985. He is also well-known for his anti-human rights rhetoric.

Bolsonaro's victory meant the military’s return to centre stage of Brazilian politics, now through democratic elections rather than a coup d’état. Bolsonaro has, in his own words, a 'completely militarised' cabinet. In March 2021, 7 out of 22 ministers are from the armed forces.

7 out of 22 ministers in Bolsonaro's government are from the armed forces

The relation between Bolsonaro and the military is in crisis after the sudden sacking of Brazil’s defence minister General Fernando Azevedo e Silva. In retaliation, the heads of all three military branches resigned.

While the military's role in the future of the Bolsonaro government might now be unclear, it still forms the backbone of Bolsonaro's political base. Brazil has refused to reckon with its dictatorial past. The military has therefore remained a credible institution capable of interfering in politics – and its support has made Bolsonaro presidential. Bolsonaro's discourse, aligned with the armed forces, also portrayed him as a patriotic hero.

The success of far-right populism, and its effects on democracy and human rights in Brazil, is closely tied with the military and the legacy of dictatorship. A lack of transitional justice measures is at the heart of Bolsonaro’s populist success, and the military's role in his government.

A slow, controlled transition of power from the military to civilians characterised democratisation in Brazil. This meant, in practice, collective amnesia towards the human rights violations perpetrated under 21 years of military rule. Unlike other countries, including its southern-cone neighbours, Brazil’s transition to democracy occurred without significant transitional justice measures.

Part of the dictatorship's legal framework remains valid in Brazil’s legal system

Over the years, the government put only sparse transitional justice initiatives into practice. These focused mostly on reparations to victims and their families. From 2003–2016, the Worker’s Party was in power. During this time, Brazil seemed more willing to reckon with its authoritarian past, developing memory- and truth-oriented projects.

This process culminated in the creation of the National Truth Commission, active between 2012 and 2014. In its final report, the Commission named 377 perpetrators of human rights violations during the military regime. It also presented an official account of 434 victims of the dictatorship.

While there have been some advances, transitional justice falls short in Brazil. Human rights trials of state agents involved in torture or forced disappearances have not taken place. Parts of the dictatorship's legal framework remain valid in Brazil’s legal system.

The National Security Law, which defines crimes against national security and political and social order, was part of the dictatorship’s structure. It aimed to silence dissent through political repression and the limitation of individual rights. This law, a symbol of the military regime, is now being used against critics of the Bolsonaro government.

As of March, Brazil counts 300,000 deaths from Covid-19. Fundação FIOCRUZ says it represents ‘the largest public health and hospital collapse in the history of Brazil’. Bolsonaro adopted a populist approach in dealing with the pandemic. He downplayed the virus, politicising vaccination, mask-wearing and the adoption of lockdown measures.

The Bolsonaro government's covid response is, according to the Lowry Institute, the worst performance by any government worldwide. Its poor handling of the pandemic has sparked strong criticism from the opposition, civil society and the media. An investigation led by the NGO Conectas and São Paulo University claims Bolsonaro had an 'institutional strategy' to spread the virus.

Bolsonaro’s far-right populism is not only dictatorship nostalgia but, arguably, a successor to the military regime

Among his critics is the digital influencer Felipe Neto, who has more than 40 million subscribers to his YouTube channel. After calling the president ‘genocidal’, Neto was accused of threatening national security by Carlos Bolsonaro, councilman of Rio de Janeiro and son of the president, and investigated and summoned by the Federal Police. After a court decision, the investigation is currently suspended. In the same week, five protesters were detained in the country’s capital for holding a sign saying 'Bolsonaro Genocida'. In both cases, the Federal Police used National Security Law as the legal basis to justify their actions.

Regardless of whether Bolsonaro’s actions can be defined as a genocide, there is clear violation of his critics’ rights to free expression. While democracy and human rights fade in Brazil, the use of a dictatorship-era law to silence dissident views is symptomatic of a process of autocratisation. Bolsonaro’s far-right populism is not only dictatorship nostalgia but, arguably, a successor to the military regime.

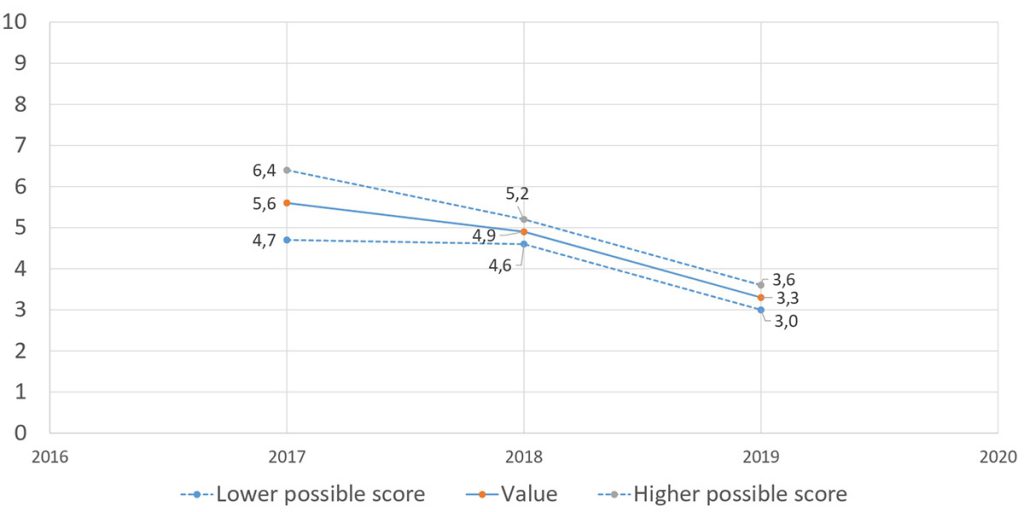

Democracy indexes show an overall decline of democratic traits in Brazil. Human Rights Measurement Initiative data is a powerful tool for tracking countries' human rights performance. Such data is also a barometer of how quickly autocratisation processes impact on those rights.

Looking at data trends over time, the effects of autocratisation under Bolsonaro stand out. From 2017 to 2019, and especially since 2018 when Bolsonaro took office, we see significant decline in Brazil's respect for the right to opinion and expression.

Government critics such as Felipe Neto have created an initiative guaranteeing legal assistance to people whose right to free speech has been violated for criticising Bolsonaro. On the other hand, while coronavirus death tolls break records in Brazil, the government commemorates a decision by a Federal Court allowing the 1964 coup to be celebrated as a ‘landmark of democracy’.

The lack of implementation of transitional justice measures during Brazil's democratisation helps explain how Bolsonaro got into power. It's also why democracy and human rights are now fading in Brazil.

By not dealing with its past, Brazil has revived authoritarianism – this time through a far-right populist leader.