Who benefits from feminism, and who loses from it? Marco Improta and Elisabetta Mannoni reveal an ideological gap between young men and women across Europe. This gap – strong in the UK, but absent in Norway – may relate to perceptions of the 'winners and losers' of feminism

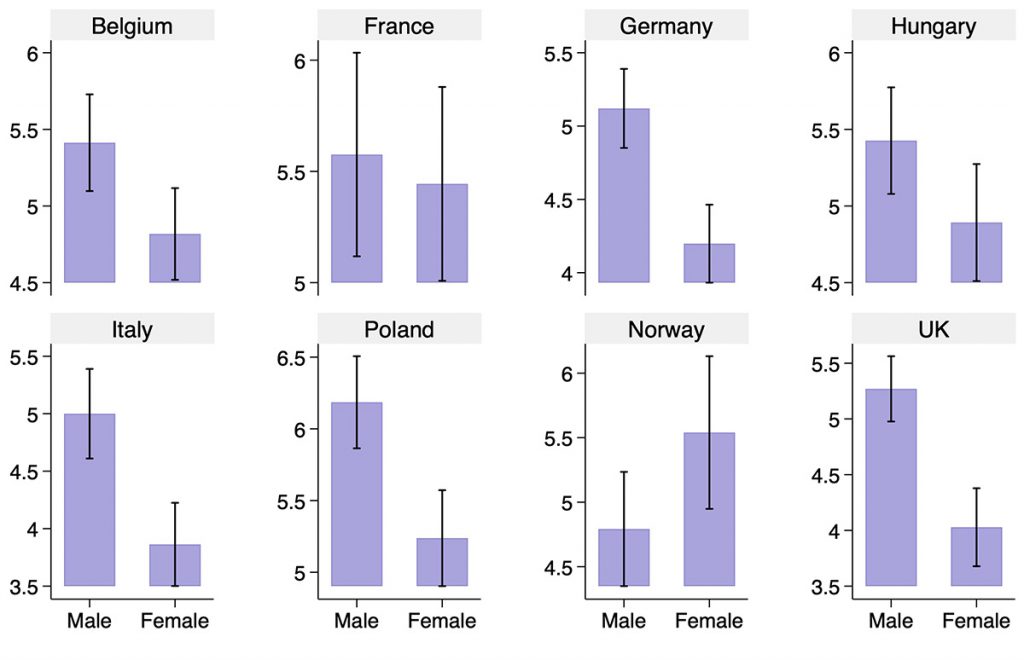

Across Europe, the political values of young people are diverging along gender lines. Our new data from the REDIRECT survey, covering eight European countries, shows that men aged 18–34 quite consistently place themselves further to the right than their female peers. This gender gap is particularly wide in Poland, Italy, Germany, and the UK. The trend holds even after accounting for education, class, or religiosity.

What’s driving this gap? We propose that part of the answer lies in the politics of gender, the increased salience of feminism, and the perception of who wins and loses because of feminism.

In many countries, feminist ideas have become central to mainstream left-wing platforms. From abortion rights and gender quotas to tackling the gender pay gap, progressive parties increasingly make gender equality a key part of their political identity. It may seem unsurprising, then, to see women on the left-side of the political spectrum. As feminism offers tangible improvements to their lives, many young women won’t settle for anything less than equal rights.

To some young men, though, feminism may feel like a threat; a path leading to someone gaining at their expense. Some may not see it as a move towards equality, but as a zero-sum game. This dynamic fuels a political divide: not between men and women per se, but between those who feel they are gaining from social change, and those who feel they are bound to lose.

To some young men, feminism may feel like a threat; a path leading to someone gaining at their expense

Research has long shown that gender backlash can influence political preferences. What we are now seeing is that this backlash is increasingly generational. Many younger men are drawn to narratives defending a more traditional social order. In such a world, masculinity is not questioned, and feminism is mocked as 'political correctness gone mad' – or just another extremism to resist as fervently as sexism.

Certain traditionalist or anti-feminist narratives offer a sense of belonging to those who feel left behind by social change. The appeal of such narratives is not only about ideas, but about identity – and that may be where their power lies.

Of all the countries we surveyed, the United Kingdom stands out for having the sharpest ideological divide between young men and young women. While young British women cluster around the centre-left, their male counterparts veer sharply to the right.

This isn’t happening in a vacuum. In recent years, the UK has become a cultural flashpoint in the debate about gender, youth, and identity. The central character in critically acclaimed TV series Adolescence represented a generation of teenage boys struggling to navigate questions of masculinity and purpose in a world of feminist progress.

This cultural conversation, then, is deeply political. Some young men find refuge in online manosphere influencers. They seek content filled with anti-feminist rhetoric that promises to 'restore order' and adamantly rejects the language of inclusion. UK educators report a surge in misogynistic behaviour, such as boys refusing to engage with female teachers, that is linked explicitly to the Andrew Tate phenomenon.

The culture war might be influencing how some young voters align politically, and how they approach daily social interactions

As a result, gender appears to be an increasingly important factor shaping political preferences among young people in Britain. Beyond media and education, the culture war might also be influencing how some young voters align politically, and how they approach daily social interactions.

Yet the story isn’t the same everywhere. In Norway, the pattern is the opposite: young men appear slightly more leftist. One explanation is that, unlike in more polarised contexts, Norway has long adopted progressive gender-equality measures – such as shared parental leave, subsidised childcare, and gender quotas – which show how more gender-equal societies can benefit men alongside women.

These are not policies that one part of the population demands while others resist with scepticism or hostility. Rather, they are widely accepted and successfully implemented policies that women and men have been enjoying for some time now. A collective win, rather than a culture war.

As Luca Verzichelli suggests in his foundational blog piece for this series, democratic disconnect today is not a single crisis but a constellation of them, cutting across institutions, identities, and the very ecology of representation. Our contribution zooms in on one of these emerging lines: the widening gendered division among young Europeans. The split illustrates how cultural change, perceived status loss and competing narratives of inclusion are generating new forms of affective and social disconnect.

Cultural change, perceived status loss and competing narratives of inclusion are generating new forms of affective and social disconnect

What lies behind this divide is not yet clear, but some leads are worth exploring. We hypothesise the contrast may reflect growing resentment and perceived status loss among some young men. This is a dynamic often amplified by misinformation and anti-feminist rhetoric that circulates rapidly in online spaces, where content creators frame backlash against feminism as a defence of common sense, traditional values, and masculine identity. If political elites overlook this divide, this ideological gap risks deepening, and could harden into a generational cleavage.

To prevent this, gender equality must go beyond abstract appeals and become visible in people’s lived experience. We must enact it through policies such as shared parental leave, accessible childcare, and anti-discrimination protections in education and the workplace.

Over time, these measures should evolve into valence issues, not positional ones: a shared democratic good, rather than a cultural battleground. They should also be backed by communication strategies that are as targeted and effective as the narratives they aim to counter – directly addressing public scepticism, pushing back against zero-sum framings, and demonstrating how such reforms benefit not just women, but society.

The next generation is watching. What they see will shape the politics of tomorrow.

The childhood seems to matter, when it comes to misogyny and antifeminism. That is the theory of Franz Jedlicka ("Misogynization" ebook).

Dorothy