The Italian Five Star Movement – Movimento 5 Stelle – has undergone a formidable split. This, and declining popularity in opinion polls, marks the twilight of Five Star’s decade-long success – and possibly the end of populist politics in Italy, writes Martin Bull

The Italian Five Star Movement today is in a sorry state. Observers must, as a result, wonder what happened to the shining new star of the Italian party system since it shot to fame in the 2013 national elections, breaking up the existing political geometry.

But the party has now endured a damaging split of immense proportions. Minister of Foreign Affairs and former Five Star Leader, Luigi di Maio, has broken away. Together with 60 parliamentarians (and a few Ministers), he has formed a new political party, Insieme per il futuro, Together for the Future.

True, splits in Italian parties, and the formation of new ones, are not unusual in Italian politics. But the sheer scale of this implosion, and its implications for the future of populism in Italy, make it worthy of attention.

The Italian Five Star Movement was, in many ways, the beacon of European populism. It was an anti-establishment movement founded not by a politician but by a comedian (Beppe Grillo) in opposition to the corruption of the mainstream Italian political parties. It was a party, it claimed, ‘neither of the left or right, but above both’.

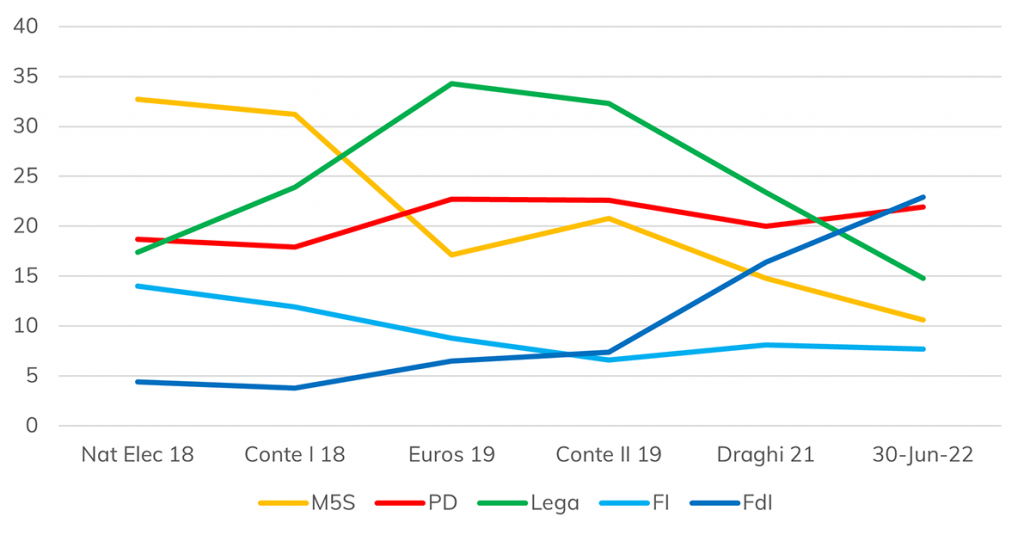

In the 2013 national elections Five Star secured an astonishing 25.6% of the vote in the Chamber of Deputies. Thus, it became the second largest party in Italy. But, true to its identity as a protest party, it refused to join a coalition with the centre-left Democrats. However, on becoming the largest party in Italy in the 2018 national elections, it could no longer resist. With 32.7% of the vote (and 227 seats in the Chamber of Deputies), Five Star formed a government in June 2018. It was joined by Matteo Salvini's right-wing Lega, under lawyer and professor Giuseppe Conte as Prime Minister.

Italy's Five Star Movement was, in many ways, the beacon of European populism. It opposed the corruption of mainstream Italian political parties, claiming to be ‘neither of the left or right, but above both’

When Salvini pulled the plug on Conte a year later, Five Star kept Conte in office. They formed a governing alliance with the Democrats in September 2019. And when Conte’s majority finally fell apart in January 2021, Five Star was instrumental in helping former banker Mario Draghi form a government of national unity. Only the far-right Fratelli d'Italia refused to join. Five Star spent the early period of its existence as a form of protest movement against the establishment. Since 2018, however, it has become a mainstay of that establishment.

And it has paid a huge price. Indeed, the 2018 election marked the high-water mark for Five Star, when it attracted 32.7% of the vote. Opinion polls since have recorded an almost consistent decline, to a mere 10.6% today. Five Star was overtaken in the polls by the Lega in August 2018, by the Democrats in May 2019, and by Fratelli d'Italia in October 2020. It now hovers only 4% above Berlusconi’s depleted Forza Italia. It is even about 4% below the Lega, despite that party’s own precipitous decline. Poor local election showings in June confirmed Five Star could be heading for wipeout in the next national elections.

Those elections are due in spring 2023. However, they might happen earlier (in October, for example) if the split causes Five Star to withdraw its support for Draghi. The Five Star split was ostensibly about the ambivalent position adopted by the President of the Party, Giuseppe Conte, and his allies over the government’s Ukraine policy.

Conte has consistently been a vocal supporter of a ‘diplomatic solution’ to the Ukraine war. He and his supporters have questioned the government’s policy of providing armaments to Ukraine. Di Maio, in contrast, has been a firm supporter of the Draghi government’s policy. He views it as imperative that, in the face of continued Russian aggression, the party line be clear and unequivocal. For that reason, he argued, he had to leave.

The Five Star split was in some ways about Conte's ambivalent position over the government’s Ukraine policy – but it also reflects an internal power struggle

Yet, if truth be known, the split also reflects an ongoing internal power struggle between the two men. It is one that Di Maio could see the prospect of losing. Some Five Star MPs are talking about withdrawing from the government and offering ‘external support’ to allow Draghi to stay in office. Draghi is having none of it. He declared that either Five Star is in the government or there is no government – meaning early elections, which nobody, Five Star especially, wants. This threat should be enough to keep Five Star on board.

Yet, for Five Star, a much bigger question looms. How and why did it manage to waste its opportunity to revitalise Italian politics over the past decade? Ultimately, its problems derive from a fundamental ambiguity about its identity. A policy of ‘neither left nor right’ had the power of attraction for a party of protest. But it left Five Star ill-equipped for office.

Movimento 5 Stelle has never been able to formulate a political identity, a vision for the country, or even a coherent programme of government

Five Star has governed with the right-wing League, the centre-left Democrats and in a national solidarity coalition. In doing so, it has never been able to formulate a political identity, a vision for the country, or even a coherent programme of government. Voters do not understand what the party stands for. Perhaps ironically, this is symbolised in the manner of Di Maio’s departure. A man who built his career on his anti-Atlanticist, anti-EU positions is now leaving a party for its failure to offer unambiguous support to NATO.

If Five Star can offer anything to other populist parties today, it is only lessons to learn from its rapid decline. The beacon of European populism has dulled considerably, and is close to going out.