Olga Vlasova delves into the intricacies of economic sanctions termination. Scrutinising global data and exploring historical precedents, she uncovers the complexities surrounding the lifting of sanctions, and how rarely they are lifted. Her analysis offers valuable insights for policymakers navigating the delicate balance of international relations

The termination of economic sanctions is a hotly contested topic. When and how might a government or organisation lift sanctions? What conditions must the sanctioned party meet for this to happen?

I propose several scenarios for sanctions termination, drawing insights from historical examples and statistical data.

In 2007, Andreas Lowenfeld defined sanctions as economic measures distinct from diplomatic or military actions, imposed primarily by states – and targeting states – to influence their policies or structures.

Economic sanctions are nuanced tools of diplomacy, balancing coercive power with diplomatic finesse

However, the definition of sanctions has since evolved to include those imposed by international and regional organisations. It has expanded to target not only states but also non-state actors and individuals. Scholars generally perceive sanctions as measures sacrificing economic benefits for political objectives. Thus, economic sanctions serve as nuanced tools of diplomacy, balancing coercive power with diplomatic finesse.

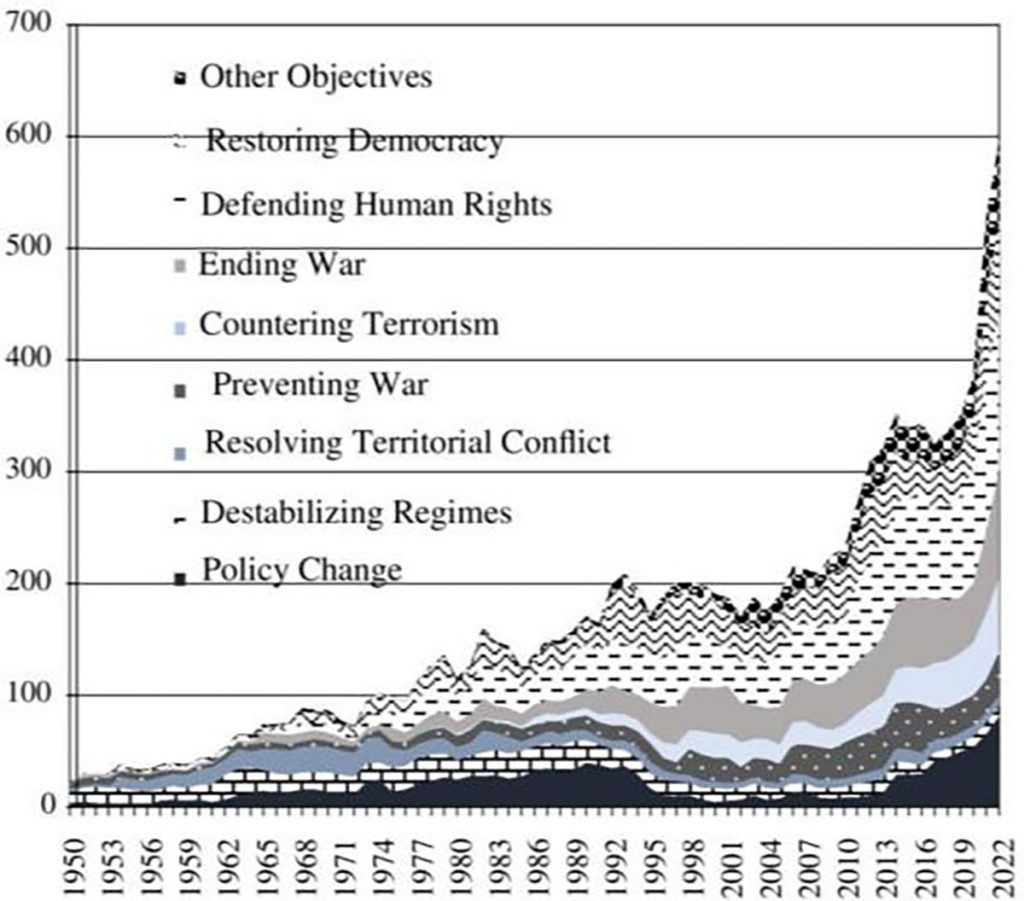

The Global Sanctions Data Base (GSDB) offers invaluable insights into the types and objectives of economic sanctions. The GSDB spans from 1950 to 2022, and documents 1,325 instances worldwide. These sanctions serve various purposes, as depicted in the graph below. They also reveal notable trends. We see, for example, a gradual increase in sanctions that aim to defend human rights. Since the early 1990s, we have seen a concomitant rise in those aiming to 'prevent war', 'end war', and 'counter terrorism'. Particularly noteworthy is the surge, since 2014, in sanctions aimed at policy change. This type of sanction reached a peak in 2022, driven largely by measures against Russia.

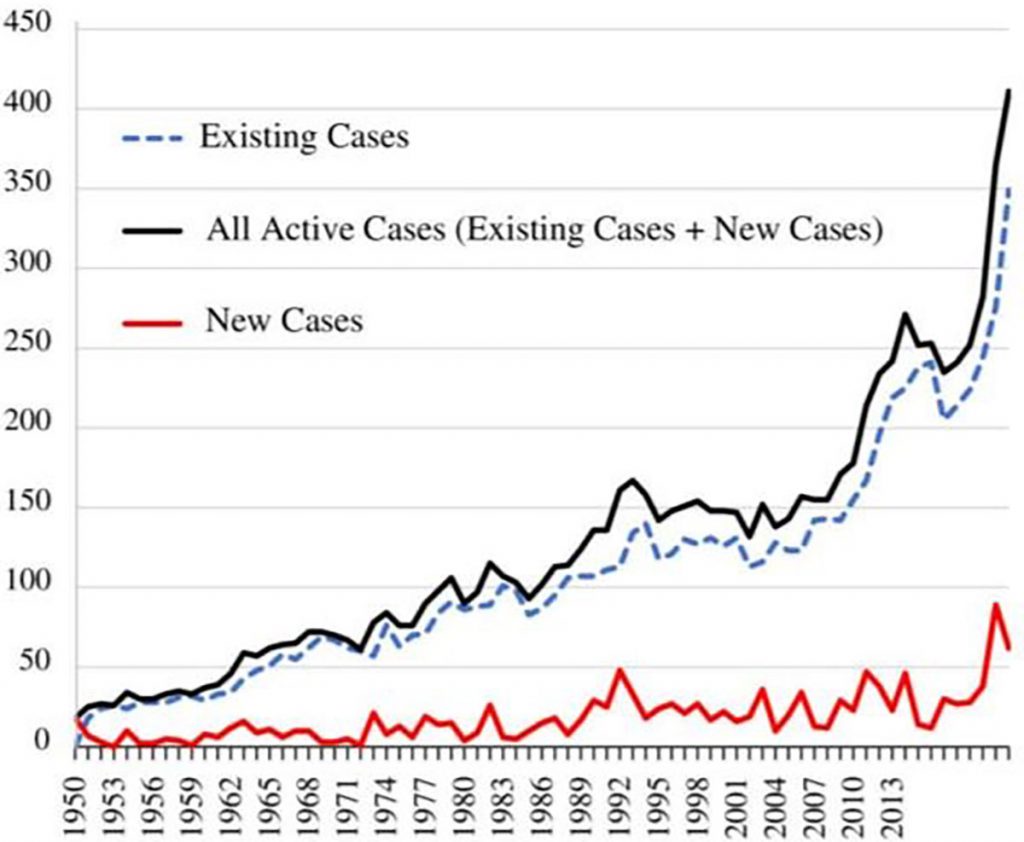

The graph below shows a growing trend in the use of economic sanctions. It also reflects the fact that only a few sanctions have been lifted. Lastly, it highlights an increasing gap between active and newly imposed sanctions. This widening gap demonstrates the statistical rarity of sanctions being lifted in the years examined.

Historical examples of specific countries that have experienced various sanctions-related pressures also demonstrate the rarity of sanctions termination.

When economic sanctions are lifted all at once, as in post-apartheid South Africa, it is generally because the sanctioned party has enacted significant political reforms. The dismantling of apartheid led to the release of political prisoners such as Nelson Mandela and, eventually, to the establishment of conditions for democratic elections.

However, sanction removal typically occurs gradually or incompletely. Historical analysis reveals that several factors can lead to the partial (at least) lifting of sanctions:

Termination of economic sanctions is rare, largely because of the intricate dynamics surrounding their implementation and removal. As time progresses, the indirect costs accumulated by the countries initiating sanctions, known as sunk costs, escalate steadily, rendering their removal increasingly challenging.

These accumulated costs motivate sanctioning entities to maintain their measures. Leaders of sanctioning states, meanwhile, face heightened political risks when they consider capitulating and lifting sanctions, particularly if the sanctions have strong domestic support.

The simultaneous lifting of sanctions by multiple actors is often unattainable as a result of geopolitical interests and divergent policy objectives

Moreover, the necessity for synchronised action among all sanction senders poses a significant obstacle to termination. The simultaneous lifting of sanctions by multiple actors is often unattainable as a result of geopolitical interests and divergent policy objectives. This lack of coordination can prolong sanctions' duration, and complicate efforts to lift them.

Certain factors can tip the scales in favour of sanction termination. Time plays a crucial role. Sanctions that demonstrably achieve their objectives within a reasonable timeframe are more likely to be lifted promptly. This shows the importance of timing in the termination process, and highlights the importance of assessing the efficacy of sanctions early on.

Conversely, prolonged maintenance of sanctions can lead to a transformation of their goals under evolving circumstances. This makes achieving the sanctions' original objectives practically unattainable.

Sanctions that demonstrably achieve their objectives within a reasonable timeframe are more likely to be lifted promptly

Furthermore, changes in ruling coalitions within sanctioning states can prompt a re-evaluation of the costs and benefits associated with maintaining sanctions. This has potential to pave the way for the removal of those sanctions.

Ending sanctions is more challenging than initiating them. When sanctions fail to achieve their intended objectives, policymakers face a dilemma. Removing ineffective sanctions risks damaging the sanctioning party's reputation as a committed enforcer of sanctions. However, maintaining trade or financial restrictions takes its own toll.

So, terminating economic sanctions remains a formidable challenge. Understanding the complexities involved – and considering factors such as political dynamics, timing, sunk costs and goal achievement – can facilitate more effective decision-making for policymakers on both sides.