Despite their shared antigenderism, populist radical-right parties’ contestation of gender and sexual equality forms a continuum rather than being homogenous across countries. Susanne Reinhardt, Annett Heft, and Elena Pavan argue that varieties of antigenderism are best understood through a party’s societal context, ideology, and voter expectations

How can we better understand populist radical-right parties’ (PRRPs) positions along the continuum of antigender politics? Populism's chamaeleonic character allows it to adapt to the socio-political context in which it operates. Populist political agendas emerge from populisms’ interactions with other sets of ideas.

Gendered opportunity structures are the contextual conditions that can both enable and constrain gender and sexual equality. The ‘varieties of antigenderism’ enacted by different PRRPs are best understood as the result of their interactions with the gendered opportunity structure: the tension between socio-political context, party ideology, and their electorate.

First, the existing contestation over gender and sexual equality influences how openly populist radical-right parties can express their antigenderism, and politicise specific issues. This includes, for example, public opinion and legal regulations. In general, PRRPs try to communicate their opposition to gender and sexual equality without appearing to be illiberal outsiders. Instead, they frame their antigender agendas in line with prevailing laws and opinions.

PRRPs communicate their opposition to gender equality without appearing to be illiberal. Instead, they frame their antigender agendas in line with prevailing opinion

Second, consistent with their people-centredness, for PRPPs 'the will of the people' is of paramount importance. Public opinion toward gender and sexual equality issues among populist radical-right parties' electorates varies across European countries – and PRRPs articulate their antigenderism to match their electorates’ expectations.

However, PRRPs’ antigenderism is not shaped only by external factors. Their positioning in the field of gender politics must align with the party agenda and ideology. Some populist radical-right parties hold neo-traditional views, preferring women to remain in the home, as mothers and housewives. PRRPs with modern-traditional views, on the other hand, promote a combination of motherhood and work. These programmatic differences also shape how nativism can be combined with gender issues. For example, neo-traditional views are incompatible with calls for Muslim women’s emancipation, while some PRRPs embrace women’s and gay rights in the context of their anti-immigration agendas.

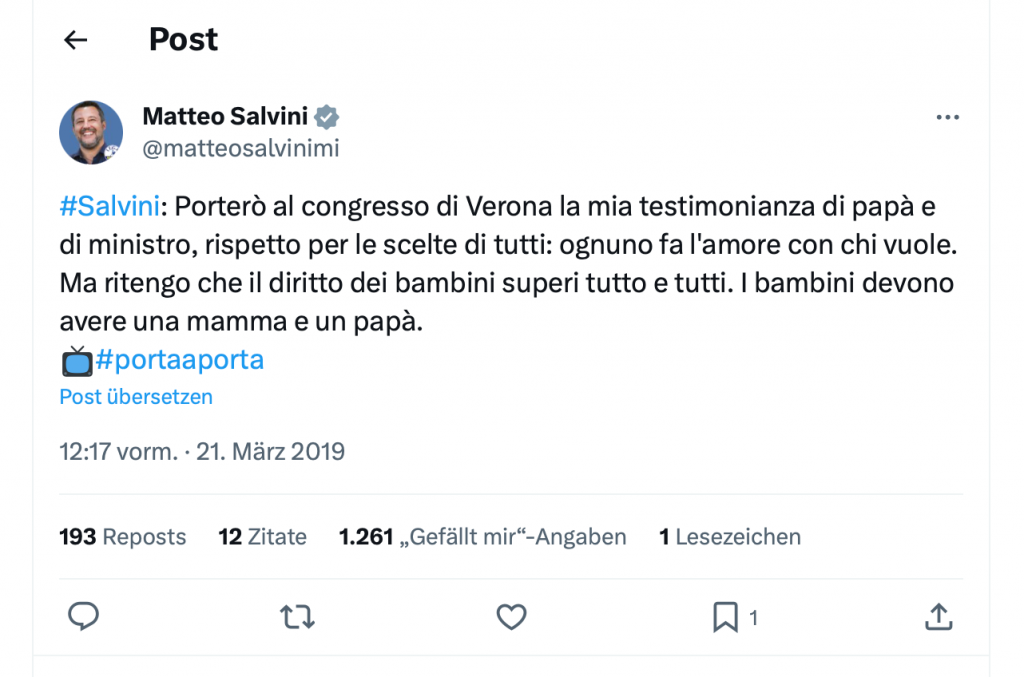

In our study, we find that gendered opportunity structures do indeed shape varieties in PRRPs’ shared antigenderism. In Italy, for instance, there is little legal protection and public recognition of LGBTQIA* rights. Same-sex partnerships are legal, but there is no equal marriage. The PRRP Lega exploits shortcomings in the protection of LGBTQIA* people, incessantly politicising non-traditional family models. For example, regarding adoption rights in same-sex partnerships, Lega leader Matteo Salvini posted: '[…] I believe that the right of children overrides everything and everyone. Children must have a mum and a dad'.

The German context is complex. There is good legal protection of gender and sexual equality, but this is counterbalanced by the anti-feminist and sexist views held by a significant part of the population. In this context, the PRPP Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) takes constant opportunities to criticise and attack women’s political and civic participation. In 2019, the party's Twitter account posted: 'Hands off our electoral law: competence instead of quota!'. Despite women’s visibility and representation in public life, AfD's strategy resonates with certain elements of Germany's population.

Conversely, in Sweden, a gendered opportunity structure promoting gender and sexual equality encourages externalisation and othering. This offers little opportunity to openly adopt anti-feminist positions. Instead, the Sweden Democrats focus on sexism and homophobia among immigrants and Muslims who, they allege, import these problems into a perfectly equal society. This femonationalist strategy is, to a lesser extent, also present in Germany and Italy. The difference arises when populist radical-right parties in more contested contexts find greater motivation to express their antigenderism openly.

The Sweden Democrats argue that immigrants – in particular Muslims – import sexism and homophobia into Sweden's perfectly equal society

As this series’ foundational blog post highlights, populism is a thin ideology. As such, it entails an agenda no more specific than people-centredness and anti-elitism. In Europe, PRRPs are characterised by a populist ideology combined with nativism. They prefer the 'native-born' over immigrants, and tend towards authoritarianism: the rejection of democratic principles and political plurality. This combination leaves behind any fixed relationship with gender and sexuality issues.

Nevertheless, within and beyond Europe, PRRPs are fuelling the current surge in antigender politics. How, then, can we explain the apparent paradox of populist radical-right parties' obsession with gender and sexuality?

PRRPs are fuelling the current surge in antigender politics. So how can we explain the paradox of populist radical-right parties' obsession with gender and sexuality?

First, antigender discourses share characteristics with populist discourses: they rely on common-sense arguments, scapegoating elites, and othering strategies. For example, populists insist it's 'common sense' that there are two – and only two – genders in Western societies.

Second, authoritarian principles within the populist radical right align well with the defence of traditional gender roles. PRRPs present patriarchy and heterosexuality as the benchmarks of a natural order – the only one that could preserve the purity of the national community, which consists of heterosexual families with children.

Finally, PRRPs combine gender and sexuality issues with their nativist agenda. They portray sexism and homophobia as problems imported to Europe by immigration rather than originating from the heart of European societies. Othering immigrants as sexist, rapists, and homophobic supports anti-immigration agendas and allows PRRPs to brand themselves as progressive defenders of women.

Consequently, there is an almost 'opportunistic synergy' between radical-right populism and antigender politics. Importantly, if we continue to look at PRRPs’ antigenderism as a shared, yet secondary trait, we risk missing that antigender politics are at the core of radical-right populism.

PRRPs do strategic work when it comes to gender social justice. By articulating their antigenderism, they shape the symbolic representation of gender and sexual equality in public discourse. In doing so, PRRPs help shape (often, narrowing down) opportunities for gender and sexual equality as a political goal. Considering the gendered opportunity structure as the macro-intersectional context in which these parties operate can help us advance one step further in this direction.

No.70 in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more