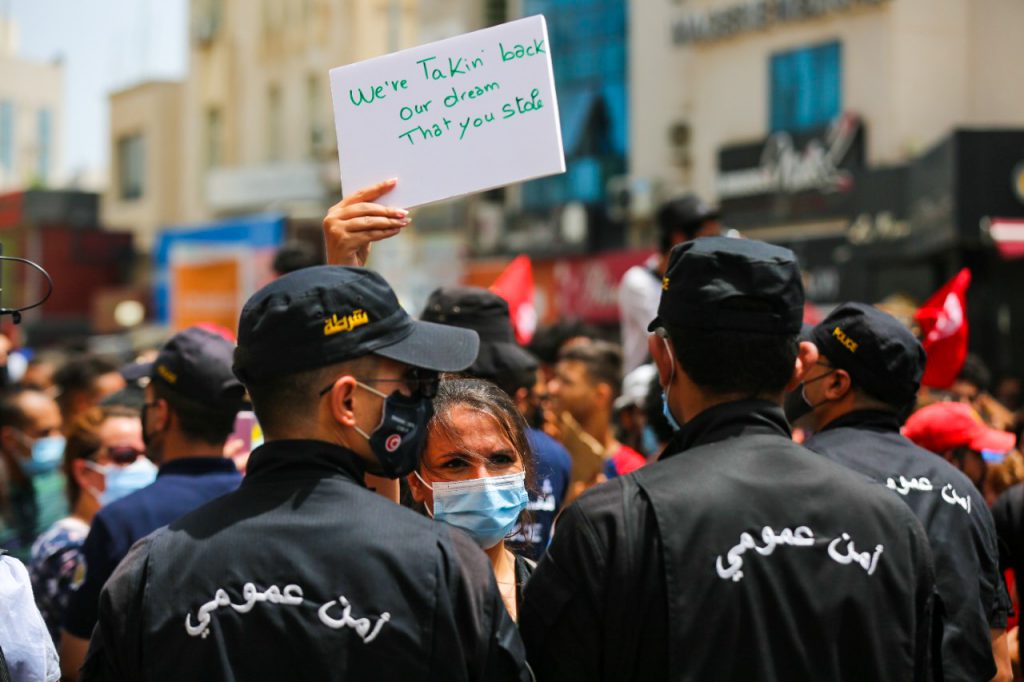

Over recent weeks, Western pundits have been quick to claim recent events in Tunisia are evidence of a ‘failed democracy experiment’. But Hager Ali and Ameni Mehrez argue that the protests are more a testament to democratic resilience than failure

Recent protests in Tunisia received global attention. Yet, in the first half of 2021 there were almost 6,800 protests across Tunisia, many largely unreported outside the country. The near-constant protests themselves don't necessarily constitute a threat to democratisation. Rather, they are an indicator that some institutional adjustments are overdue.

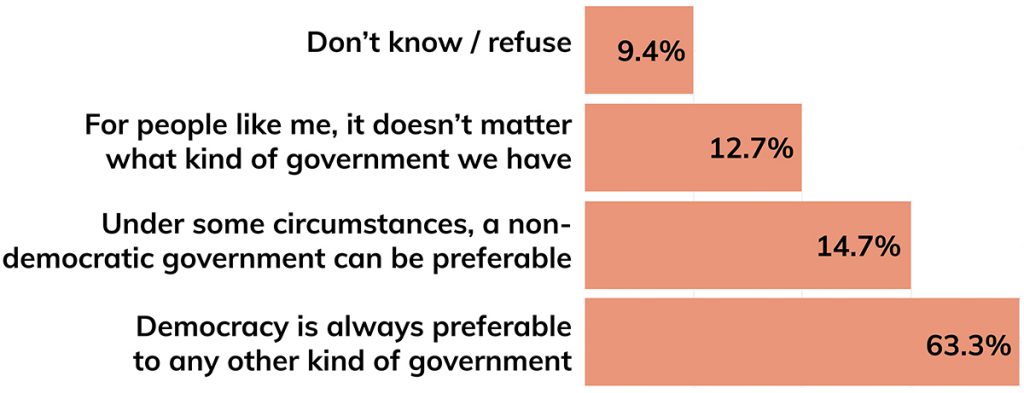

Citizens took to the streets recently to highlight the current administration’s failure to meet citizens’ recent and pre-Arab Spring demands. But this dissatisfaction does not extend to democracy itself, as Arab Barometer data shows:

That, of course, raises the question of why, if approval of democracy is high, protests are so prevalent in Tunisia. It is a consequence of a combination of two factors. First, the legal framework hinders governance because it forces ‘consensus-building’ at all costs, even though ideological divisions between the coalition blocks are salient. Second, many political parties are still in their infancy and struggle to connect with voters.

Governing elites are busy with consensus-building. Citizens, meanwhile, are more concerned with socioeconomic grievances, but have no effective parties that can articulate their demands and interests.

The current electoral system curtails democratic development through its legal arrangements. As stated by Law n°16 of 2014, Tunisian elections are based on a closed-list proportional representation system with a so-called larger remainder method.

In 2019, out of 217 seats, the electoral quotient allocated only 54. (The electoral quotient is the number of valid votes divided by the number of seats per electoral constituency.) Almost three-quarters of MPs obtained seats with fewer votes than required by the electoral quotient number. So, the largest remainder method does not properly reflect the will of the people.

No party can win the required 109 majority of seats in parliament. Thus, since 2011, parties have had a hard time forming governments. The leading Ennahda party, for instance, appointed the proposed government of Habib Jemli after the 2019 parliamentary elections. More than half of MPs rejected the appointment.

More importantly, the need to form parliamentary alliances to approve laws led to political stagnation on most key reforms. It also led to a crisis between the legislature, judiciary and executive. In January 2021, for example, parliament approved Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi's ministerial reshuffle. President Kais Saied then rejected it, and prevented the new ministers from swearing the oath of office.

The composition of parliament is so heterogeneous that it is very difficult to form coalitions. In 2016, a government of national unity was formed through the Carthage Agreement. Its main goal was to bring political stability after a long crisis through consensus-building between secularists and Islamists. While the Agreement did pacify ideological conflicts in parliament, it did not address the political fragmentation and polarisation within society.

While the Carthage Agreement did pacify ideological conflicts in parliament, it did not address the political fragmentation and societal polarisation

Another aspect of Tunisia's dysfunctional parliament is its imbalanced and volatile party landscape. The vast majority of parties that won a seat in 2019 formed post-2011. Most of them were at the secular end of the political spectrum.

The secular Afek Tounes Party, for example, was founded in 2012. Afek Tounes merged with other secular parties to form the Republican Party, which then disappeared after 2019. Nidaa Tounes, a secular catch-all party, formed in 2012, but lost a majority of its voters to the newer Tahya Tounes Party, led by Prime Minister Youssef Chahed – a former Nidaa Tounes member. In the secular camp, Nidaa voters disapproved of Carthage Agreement; between 2014 and 2019, the party lost almost all of its parliamentary seats.

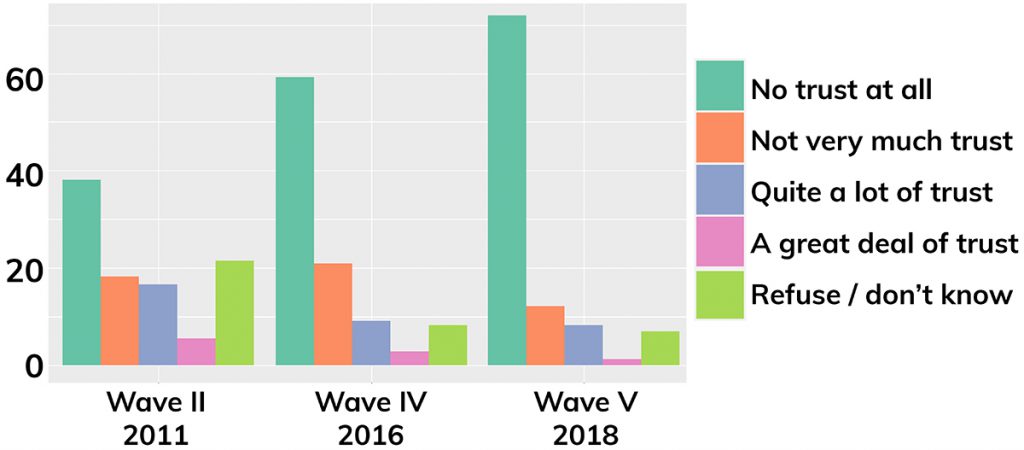

distrust in political parties is not only high, it has increased drastically since the Arab Spring of 2011

The Ennahda movement, on the other hand, emerged in the 1980s, taking inspiration from the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. Over the years, the movement built human capital through disciplined voters and welfare activism. The Brotherhood also attracted a sympathy vote because the Ben Ali regime had previously subjected it to persecution.

Ennahda, then, has a long history of mobilisation, human capital and religious infrastructure to bank on. But secular parties lag miles behind in their overall institutionalisation, partisanship, and even physical infrastructure. Arab Barometer Data from Tunisia shows distrust in political parties is not only high, it has increased drastically since 2011:

Legislation is strongly conditional on consensus-making between two ideologically opposing camps. Many political issues beyond secularism-versus-Islamism, therefore, including prevalent socio-economic grievances, fade in comparison.

Voters strongly distrust the volatile party landscape, while parties fail to connect to voters, who take to the streets instead. Tunisia’s political playing field is unbalanced from the get-go, because of the laws of the game, and because of its institutional prerequisites. And long after democratic kick-off, parties are still struggling to form their teams.

Attitudes towards democracy remain highly favourable in Tunisia. It is therefore important not to misinterpret the recent uprisings as in some way ‘anti-democratic’. The Carthage Agreement served the important purpose of reconciling secularists and Islamists in parliament. But it also created different problems in the longer term, with ramifications for a range of other issues, from institutions to voters. Opposing parties are gridlocked in a forced consensus. Voters have other concerns, yet cannot rely on existing parties.

It is important not to misinterpret the recent uprisings as in some way ‘anti-democratic’

The electoral system and problems with Tunisia’s political parties erode democratic stability. They will likely remain salient issues for some time to come. Societal divisions are common, and we should not pathologise them on their own.

Party and electoral systems need to align more closely with underlying societal divisions to remain functional. The Tunisian electoral laws are in urgent need of reform to tackle this challenge.