The EU has failed to support democracy and political change in the Middle East and North Africa. Maria Gloria Polimeno argues for a more inclusivist social approach, and a revision of the EU's foreign policy towards the region

2021 marks a decade since uprisings broke out in major Middle Eastern and North African cities under the slogan Eshab yurid isqat al-nizam / The people want the downfall of the regime.

These uprisings exposed regime violence against civilians in Egypt, Syria, Bahrain and Libya. Protests also reflected social class struggles against neoliberalism and clientelism, which acted as accelerators of dissatisfaction.

The EU is an important political actor in the Mediterranean. Through the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI), and its financial arm, the European Neighbourhood Partnership Instrument (ENPI), it putatively strives towards achieving political change, democracy, social justice and a reduction in corruption.

These goals stem from the 2012 transitions, when the EU emphasised democratisation, and supported the people’s demand for change. In 2016 it promoted the Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme and in 2019, it ratified an agreement to promote democratisation, despite acknowledging the significant deterioration of human rights in the region.

Yet, despite all the rhetoric, the EU has failed to invest properly in achieving these goals. Instead, it has supported the internal restoration of business elite circles within which the military and old elites play a decisive role. And it has overlooked the domestic political structures through which autocrats rise and fall.

Most of the EU’s actions in the region, therefore, have ended up supporting a superficial revolution, and have failed to tackle the underlying structural problems that beset most Middle Eastern and North African countries. The EU has failed the Middle East and its people, tarnishing its image, especially among young people.

The EU also failed in its efforts towards achieving cohesion in Europe's approach to the region. In recent years, EU member states have preferred to pursue their own foreign policy agenda in the Mediterranean to protect national economic-military interests.

the EU failed to tackle the underlying structural problems that beset most Middle Eastern and North African countries

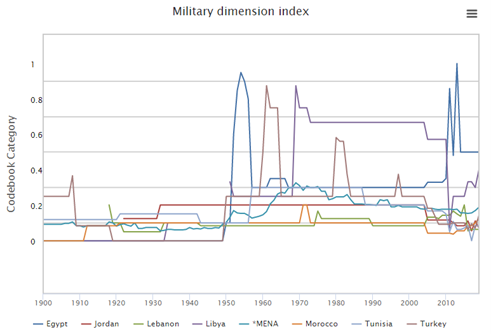

Italy’s management of the Libyan crisis, for example, ended up restoring dialogue with general Haftar. Italy’s military trade deal with Egypt neglected EU citizens’ protection, human rights protection in post-2013 Egypt and the drive towards demilitarisation, ignoring the ENPI’s goals. And France recently consolidated diplomatic relations with al-Sisi's Egypt under the pretext of pursuing the war on terrorism and deradicalisation, neglecting the brutality of the regime. Figure 1 reveals how military presence in the Middle East and North Africa region has increased, resulting in the erosion of civil rights and democracy.

Figure 1: Analysis of military presence in infrastructures of Arab states

Source: V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg. Last accessed January 2020

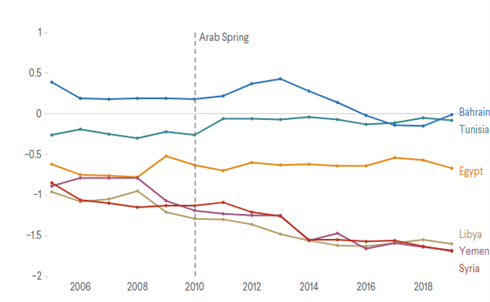

The restoration of militarism is the result of a misguided democratic model in the region, coupled with EU weakness. Military and political deals with hybrid regimes in the region reveal the EU’s internal fragmentation and a tendency towards protecting business interests. As Figure 2 shows, following the Arab Spring, Egypt, Syria, Yemen and Libya transitioned towards other forms of autocracy, rather than democracy.

Figure 2: Democracy achieved, 2006–2020

0 = Not free / not democratic

Above 0 = partially free / free / democratic

Source: Council on Foreign Relations

In 2020, Freedom House reported for the fourteenth year running a decline in global freedom caused by the erosion of democratic values and principles, and denounced the lack of efforts to reverse this trend.

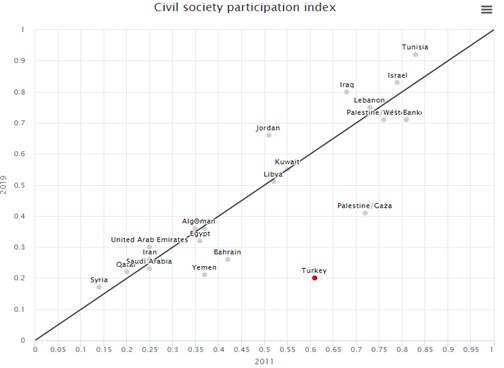

V-Dem Project data reveals how the 2011–2012 transitions failed participatory democracy. The post-2012 ‘electoral autocracies’ have embedded new layers of authoritarianism in the way elections are managed: they are closed and non-competitive in comparison with the pre-2011 semi-competitive, albeit highly corrupt, elections.

Figure 3 shows how, since 2012, civil society participation in political decision-making has been sharply restricted.

Figure 3 Civil Society Participation Index

Source: V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg

Ten years after the Arab Spring, countries in the Middle East and North Africa remain socially and structurally dysfunctional. In Tunisia, for example, there are severe limits on inclusivity; in Egypt, high levels of violence and repression; and in Syria, refugee displacement.

Added to the mix are increasing levels of poverty. According to World Bank data, the poverty gap in the region increased from 0.4 in 2010 to 2.1 in 2019. And social protection worsened sharply between 2015 and 2019.

Ten years after the Arab Spring, countries in the Middle East and North Africa remain socially and structurally dysfunctional

Political systems in the region have become more structurally fluid, which political elites have been able to exploit to stay in power. To reverse this trend, we need stronger, more centralised EU leadership that implements revisionist and inclusivist social policies.

These policies should bypass internal divisions in EU foreign policy, take social security properly into account, and reshape the EU's obsolete, reactive approach to the securitisation of borders and migration. The EU needs to act quickly.