Actors from across the political spectrum, including the populist far right, have voiced concerns about safeguarding democracy amid the coronacrisis, writes Sabine Volk. But their different understandings of democracy reveal Germany’s political polarisation, rather than its unity

The Covid-19 pandemic has had detrimental effects on democratic systems across the globe. Powers of the legislature have declined in favour of the executive, and citizens have suffered severe cutbacks in their fundamental democratic rights.

Even in established democratic systems such as Germany, some of the very principles of liberal democracy have been jeopardised. The parliament disempowered itself in the name of a 'state of exception', and citizens’ democratic rights to assembly and protest have been infringed over an extended period.

At the onset of the pandemic, European governments, politicians and civil society were not unduly worried about such democratic ‘infringements’. Indeed, biopolitical perspectives focusing on public health dominated political debates.

When addressing their electorates, the heads of state and government of established European democracies such as Spain, France, the United Kingdom, and even Sweden did not appear greatly concerned about the consequences of restrictions for their democratic systems.

In Germany, possibly because of its recent history of two totalitarian regimes, the situation has been different. As I show in my recent research, amid the crisis, political actors from across the institutional, ideological, and geographical spectrum have repeatedly voiced their commitment to democratic principles.

In March 2020, Chancellor Angela Merkel (CDU) made a much-praised primetime television address to the nation. She underscored her government’s efforts to comply with democratic values of accountability and transparency, explaining pandemic restrictions:

This is part of being an open democracy: that we make political decisions transparent and explain them; that we justify our actions and communicate them to make them understandable.

Chancellor Angela Merkel, ARD, 18 March 2020

Executive actors at the regional levels have also claimed to be safeguarding democracy. Michael Kretschmer (CDU), governor of the eastern German region of Saxony, visited a not entirely legal anti-lockdown demonstration in the city of Dresden to learn about protestors’ discontent. In a subsequent interview, he framed his controversial, unmasked visit as an attempt to prevent the further undermining of democratic values after weeks of lockdown:

We live in a liberal democracy. Here everybody can voice his opinion and contradict the elected representatives.

Michael Kretschmer, Funke-Mediengruppe, 22 May 2020

Not engaging in dialogue, he claimed, would have detrimental consequences for German democracy. 'The number of demonstrators will increase if everybody who has a critical position is forced into a corner and excluded as an interlocutor'.

The political establishment has made repeated claims to be protecting democracy during the crisis. Despite this, far-right challengers were quick to contest governmental policies.

Germany’s most sustained far-right protest movement is the so-called Patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the Occident (Pegida), from Dresden. Pegida was among the first groups to claim that it is 'peaceful' activists, not elected representatives, who defend democracy. Not long into the pandemic, a large-scale anti-lockdown movement joined forces with Pegida.

Far-right Pegida drew a parallel between pandemic politics and the past communist dictatorship in East Germany. Activists argued that democracy today is worse than under communism, because 'we exchanged the rascals for full-blown criminals in 1989 and 1990'. They interpreted the pandemic as a welcome opportunity for the German establishment to install supposedly totalitarian and oppressive state structures.

As a consequence, from April 2020 onwards, Pegida mobilised against the alleged Corona-dictatorship under Angela Merkel. Activists organised virtual events and street demonstrations 'for our democracy', 'for our constitution', and 'for our civil rights':

Ostentatious displays of copies of Germany’s Basic Law (the Constitution) reinforced Pegida’s claims to be legitimately representing democracy and constitutionality.

The key to explaining competing claims to be safeguarding democracy by federal, regional, and civil society actors lies in the different dimensions of modern liberal democracy itself. In claiming to defend democratic principles, the different political actors focus on different aspects of what is a multi-dimensional concept.

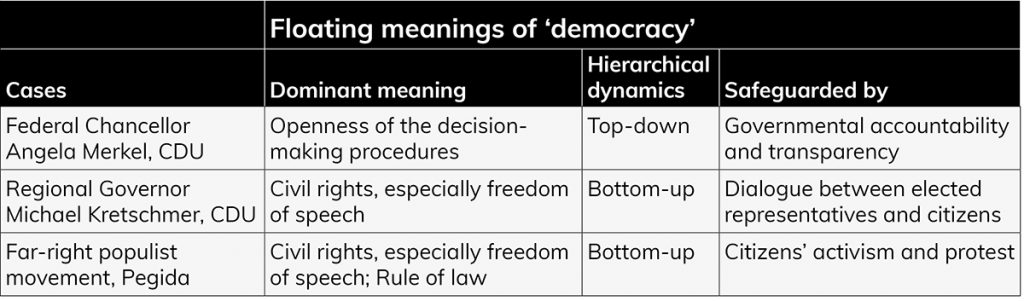

During the early days of the pandemic, Chancellor Merkel expressed a top-down understanding of democracy. She emphasised the openness of decision-making procedures based on governmental accountability and transparency. In contrast, Governor Kretschmer adopted a bottom-up approach, focusing on civil rights, especially freedom of speech, in dialogue with elected representatives.

For far-right Pegida, democracy also stands for civil rights. But the group understands grassroots activism and protest as the only means to safeguard freedom of speech. On the streets, activists claim the right to delegitimise the institutions and representatives of ‘real-existing’ democracy. Also, the populist far right suddenly seems to set great store by the liberal pillar of German democracy. In fact, it is placing the constitution at the centre of its campaign.

The different understandings of democracy held by Merkel, Kretschmer, and Pegida point to an unstable, and potentially volatile, political situation. In the run-up to the September 2021 parliamentary elections, political polarisation is increasing. Far-right allegations against the elected representatives reflect this polarisation, as does a decline in grassroots support for crisis management politics. At the same time, despite their enhanced powers, federal and regional governments have demonstrated a near complete lack of control during the pandemic.

There does not seem to be any kind of consensus over the meaning of democracy. Even so, the renewed concern for democratic values might strengthen the German democratic system in the long term.

The new government must reintegrate the alienated segments of society. A key way it might do so is by involving civil society actors in the democratic decision-making processes.