Niva Golan-Nadir examines the diverse strategies state institutions use to manage unpopular policies while keeping the core of those policies intact. In Israel, citizens are only partially content with government measures to meet their demands. Crucially, however, Israelis are satisfied enough to prevent civil pressure on state institutions

Citizens in modern democratic states enjoy civil rights and liberties that no other form of regime may offer. The democratic framework of such states guarantees the sovereignty of the citizenry. The will of the people should therefore determine state policy, so you might expect state policy to align with openly expressed public will.

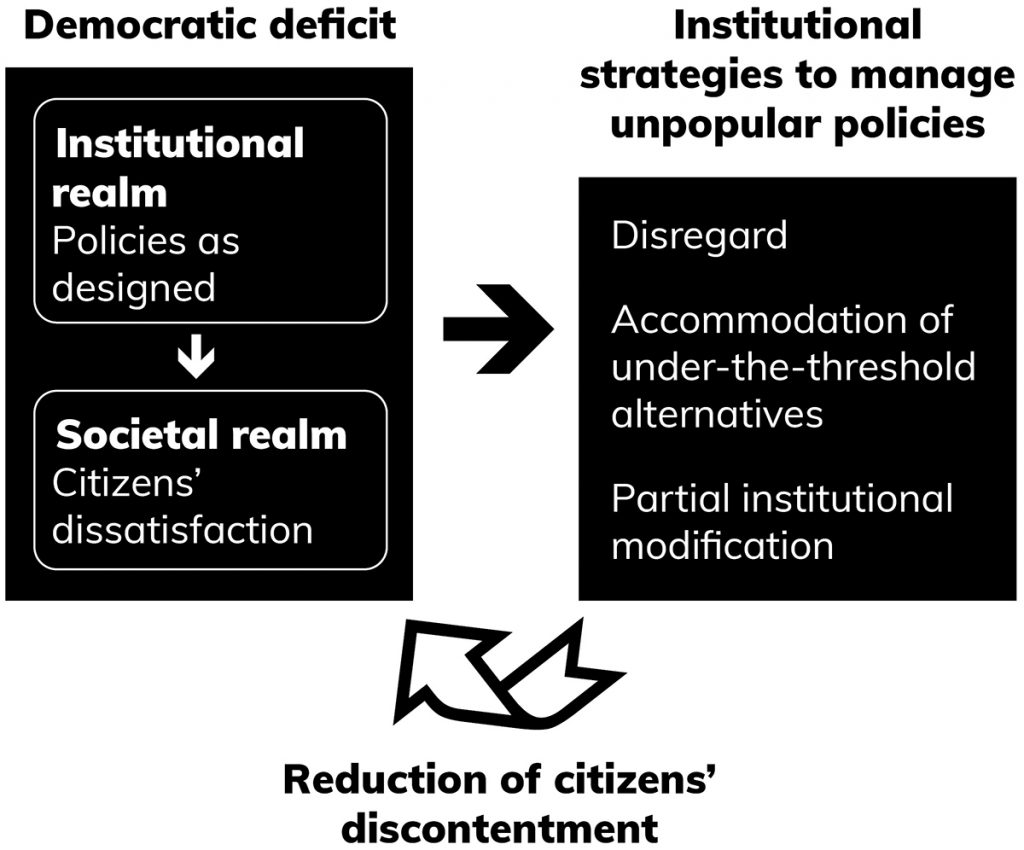

Yet that is not always the case, because sometimes preference change has no direct impact on policy modification. This constitutes a democratic deficit. Unpopular policies might therefore endure, because state institutions manage them in different ways. Governments do this to meet societal demands, at least partially, while the core of their existing policies remains untouched.

Governments steer unpopular policies through distinct strategies. Moreover, state institutions adjust these strategies in different ways in response to societal discontent. The table below shows three strategies governments can employ.

| Strategies | Features |

|---|---|

| Disregard | Policy remains intact. No actions taken by institutions. Civil society might offer alternatives that are unrecognised, but not banned. |

| Accommodation of under-the-threshold alternatives | Policy remains intact. Under the legislative threshold, arrangements are introduced by different initiating sources, such as NGOs or the judiciary system. The alternatives are recognised as normatively and juristically acceptable, and grant most legal rights and privileges to dissatisfied citizens. |

| Partial institutional modification | Core of policy remains intact. Changes that do not undermine its core are officially introduced. |

All three strategies aim to keep state policies intact. However, they require different adjustments by state institutions. What's more, the strategy chosen depends on the characteristics of the policy in question. Strict, dichotomist (yes or no) policies, for example, cannot allow arrangements that are under the legislative threshold. Nor can they accommodate partial institutional modification. More flexible policies, on the other hand, do allow such alternatives.

Israel defines itself constitutionally as a ‘Jewish and democratic state’. This unique official character, however, creates a basic difficulty in separating state and religion. Among Jewish Israelis there is broad consensus that Israel should be a ‘Jewish state’. Deep controversies exist over the meaning of the term, however.

Several policy principles are fundamental to Orthodox Judaism. These policies are Jewish Saturday, Shabbat (that includes the ban on public transport); Family law (Orthodox marriage and divorce – no civil marriage); and finally Kashrut (keeping Jewish kosher laws of food in public institutions by the Chief-Rabbinate).

Public opinion surveys on religious policies show that the majority of Jewish Israelis want these fundamental policies to change.

In early 2022, I conducted a survey with the Institute for Liberty and Responsibility at Reichman University. Among respondents, 65% said they completely or mostly agree with allowing a civil marriage route in Israel in addition to the religious one. If we divide respondents into levels of religiosity, the secular segment, unsurprisingly, expressed the highest level of support. However, other, more religious segments showed some support, too: secular 85.6%, traditional 61.3%, religious 33.3%, ultra-Orthodox 19.6%.

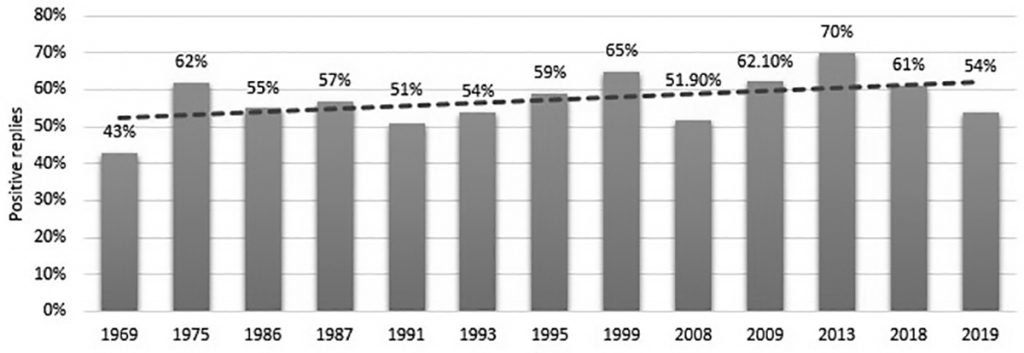

Another example is support for public transport on the Shabbat. The graph below shows how support for this has shown a general upward trend.

In my survey, 63% of respondents said they completely agree or mostly agree that Israel needs to provide public transport on Saturdays, except in highly religious areas. If we divide respondents into levels of religiosity, the most secular group, again, shows highest support for this. But even other segments completely or mostly agree: secular 88.6%, traditional 61.9%, religious 20%. Only the ultra-Orthodox segment disagreed entirely.

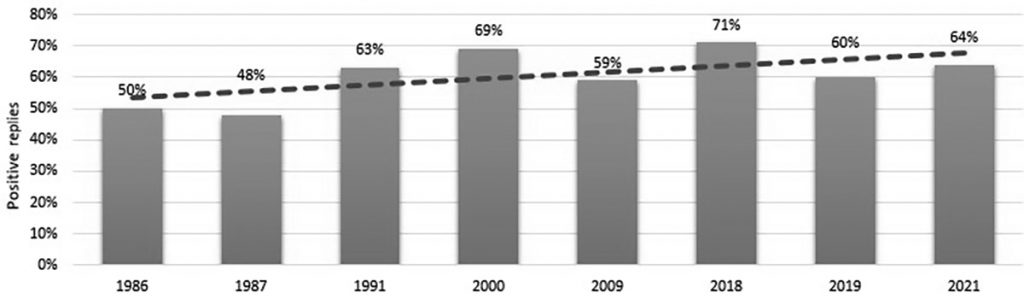

A third example is demands to remove the Rabbinate's monopoly on kosher food inspection. A number of surveys collected by the Viterbi Family Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research at the Israel Democracy Institute show that the Rabbinate's monopoly over kosher food inspection is much debated by Israeli Jews. Indeed, in 2004, 55% of people claimed to have 'no trust' or 'very little trust' in the Rabbinate. By 2009, this figure had increased to 58%. In 2013, it dropped a little to 53%, but by 2017 an overwhelming 72% expressed no or very little trust. A 2018 survey revealed that 66% of respondents believed the Rabbinate to be corrupt. The following year, 64% called for the government to revoke the Rabbinate's monopoly on kosher food.

In my 2022 survey, I asked whether the Rabbinate's monopoly on kosher food inspection should be revoked. A majority 65.3% of respondents indicated they completely or mostly agree. Dividing respondents into degrees of religiosity, the division remains. 88.1% of those defining themselves as secular agree completely or mostly with revoking the monopoly. This compares with 66% of those self-defining as traditional, 28.4% of religious, and even 6% of ultra-Orthodox.

Clearly, then, strategies to reduce societal dissatisfaction in Israel enjoy varying success. The state's disregard (strategy 1) of societal and local government's initiatives to provide free public transport on Saturdays gains 35.2% approval.

Likewise, the Israeli state has accommodated under-the-threshold alternatives (strategy 2) in the case of marriage. The state's recognition of varied common-law and other judicial couplehood agreements that may grant couples equal rights yet no official 'married' status, gains 45.6% approval.

Meanwhile, partial institutional modification (strategy 3), gains 54.3% approval. The Bennett government has permitted various Orthodox (though not Conservative nor Reform) organisations to officially and legally inspect kosher food, removing the Rabbinate's monopoly.

All three strategies aim to keep the state-religion relationship intact. Yet each requires different adjustments by state institutions.

The results of my survey should have implications for the way policies are designed and maintained in democracies. Its findings demonstrate the enduring power of institutional designs in democratic states, often long after these policies cease to represent public preferences. This goes against the core of classic democratic theory, which stresses the continuing responsiveness of government to citizens' preferences.

Rather than modifying unpopular policies, state institutions steer them through distinct strategies requiring different levels of adjustment to societal discontent. Evidently, these strategies do succeed (though not entirely) in reducing discontent among the population, and preventing civil pressure on state institutions.