The EU’s promotion of LGBTI human rights has provoked disputes over these rights, and the way they are promoted. Focusing on civil pluralism and democratic consolidation would make the EU a more reflective and effective actor, argues Markus Thiel

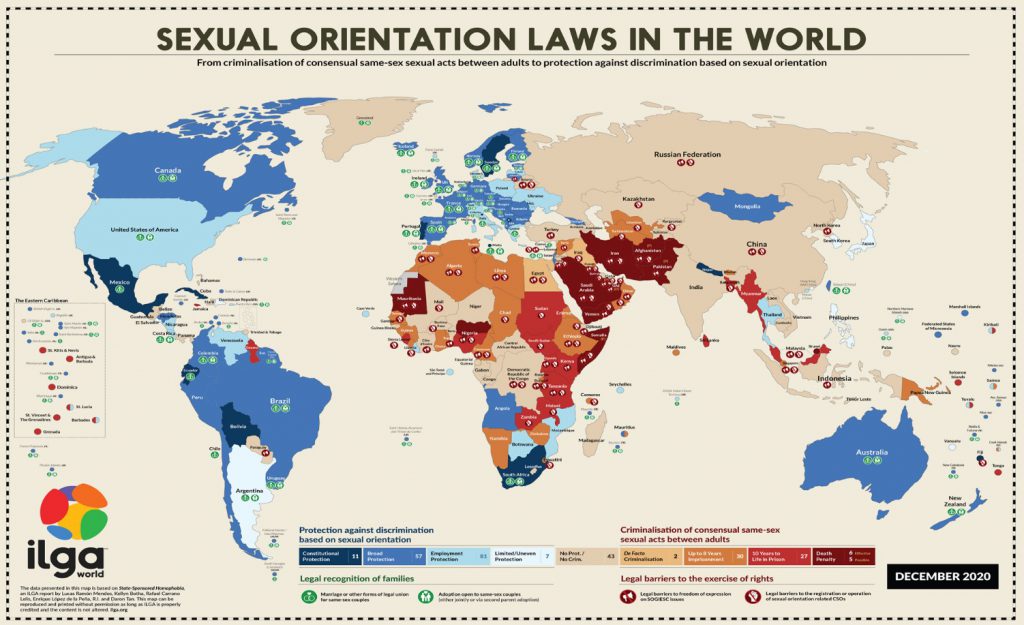

As a norm-based global actor, the EU emphasises human rights for LGBTI people in its internal and external policies. Thus, it sets a powerful example. Yet disputes over those rights policies, and the way they are promoted, have emerged in bilateral relations between the EU and other states in recent years.

Europe’s colonial history, and the fact that the bloc is the world’s largest provider of development assistance, only add to such disputes. The increasing politicisation of European LGBTI people is also a contributory factor.

The EU contributes to a rights-enabling global environment. However, in my recent book, I argue that the often inconsistent, highly visible and normative diffusion strategy evokes norm contestation.

Hence, the EU should self-reflectively reassess its external LGBTI rights promotion to avoid negative unintended consequences. It must address human rights deteriorations within broader democratic regressions.

No uniform rights standards exist within the EU region. Yet EU institutions attempt to jointly formulate and implement guidelines for the external promotion of LGBTI rights. Each institution contributes to this policy area depending on their competence to act, and their degree of agreement on LGBTI rights.

For example, the Commission and the European Parliament mainly monitor LGBTI rights in potential accession and neighbourhood countries. Meanwhile, the Council of the EU in 2013 developed specific foreign policy guidelines for countries it engages. North-South and especially East-West differences among EU members, however, condition the rather weak consensus on external LGBTI rights promotion. Other countries notice such incoherent formulation and execution of rights policies, too.

But the EU’s global LGBTI rights promotion operates in difficult terrain. Normative engagements are often entangled with conditional offerings. These include accession to the EU, access to its markets, visa liberalisation offers, and aid disbursements. Moreover, the EU visibly promotes LGBTI rights as benchmark criteria for EU membership, or in its actions in the UN’s Human Rights Council. LGBTI rights may, for example, be a condition for receiving development aid. All this has led to noticeable tensions with countries located in the Global South.

the EU promotes LGBTI rights as benchmark criteria for EU membership – and conditions development aid on respect for such rights

In contrast, EU delegations on the ground aim at building trust. They seek to depoliticise LGBTI rights, and to avoid the EU’s interventionist approach in promoting them.

Arguably the most effective case of EU LGBTI rights promotion policies is their successive implementation in countries that aim to join the Union. In these cases, the ‘Copenhagen criteria’ for accession specify, among other conditions, a respect for fundamental and minority rights.

In the process, candidate states experience a politicisation of LGBTI rights through required policy changes and visibility measures. Once they join the EU, however, the monitoring process ends. As a result, some reverse what I call ‘Potemkin reforms’ (akin to the fake Russian villages). These superficial policy adaptations intended to satisfy EU institutions are then later reversed.

LGBTI rights promotion policies enjoy greatest success in countries that aim to join the European Union

For instance, governments may use popular referenda to revoke initially instituted sexual equality rights. This has happened in Croatia, been attempted in Romania, and is planned in Hungary.

Episodes such as these demonstrate how LGBTI rights promotion is rather contingently based on political commitments by states, and on the advocacy of (trans)national activists. Moreover, rights promotion necessitates a domestic internalisation of tolerance norms.

Similarly, the 16 countries from Ukraine to Morocco in the EU Neighbourhood Policy, where membership perspective remains distant, show few positive results. The Neighbourhood Policy similarly requires commitments to human rights and gender equality. However, reviews show that often self-serving EU relations hindered LGBTI rights advances, while most democracy indicators point to stagnation there.

In terms of development policies, next to different geographical preferences and colonial linkages, the primacy of establishing trade relations continue to make a coherent development policy difficult to achieve. Furthermore, conditionality, i.e. the reduction or negation of development assistance when set conditions are not met, contributes to unequal power relations between the EU and the Global South.

Disputes with individual recipient countries or joint EU-Africa summit clashes over the EU’s rights promotion stem from an interventionist yet inconsistent strategy. The EU has frequently reprimanded African governments on LGBTI rights. In response, African leaders point to Europe's colonial criminalisation of homosexuality, and decry the EU’s legitimacy when disregarding human rights at EU borders. Such tensions are difficult to resolve. Many regard the EU’s rights agenda as hypocritical in the face of its protectionist trade, security, and refugee policies.

many regard the EU’s rights agenda as hypocritical in the face of its protectionist trade, security, and refugee policies

Finally, the EU accesses and strategically uses UN bodies and other regional organisations. However, the EU’s volatile status as a UN observer constrains its work there, too.

Another EU-internal problem emanates from the fragmentation of EU representative and executive functions. In the UN, for example, EU member states pursue their foreign policies as principals. The EU’s diplomatic service, however, has the task of coordinating common policies.

The UN Human Rights Council represents an opportunity structure for the promotion of LGBTI rights globally. Yet the way the EU member states highlight sexual rights norms in often asymmetrical power relations to individual states and blocs leads to polarisation.

Considerable constraints remain for a more meaningful promotion of LGBTI rights. Internally, the volatile standing of EU LGBTI policies within the EU, and rapid but reversible normative transformations in the case of the EU's enlargement policy, present challenges.

Externally, limited incentives and selective engagement (in the case of EU Neighbourhood Policy), postcolonial resistance and conditionality (in the case of development policy), and a politics of optics (in the case of rights promotion at the UN) should prompt the EU to rethink existing promotion strategies.

Given the normative disparities, geopolitical pressures, and constraining limits of the EU’s LGBTI promotion thus far, a broader focus on enabling civil pluralism and democratic consolidation would make the EU a more reflective and effective actor.