Citizenship is a contested and multifaceted concept. Yet despite their many differences, Germans see citizenship as something more than simply a legal status. Franziska Maier finds that common to all German citizens is a desire for connectivity

Football is political, and this year's delayed European Football Championship has been no different. In the German debate, news outlets focused in particular on footballer Leon Goretzka. Commentators claimed he is made for the new Germany / Wie gemacht für das neue Deutschland and represents the image of the good German / Das Bild vom guten Deutschen. German media see the footballer as symbolic of a changed nation: progressive, inclusive, and tolerant.

The influx of refugees from 2015 onwards revitalised a debate around the requirements for German citizenship. It featured the controversial idea of a distinct set of German cultural values in the form of a 'lead culture' (German issues in a nutshell).

Similar debates were sparked in response to changes in 2000 to Germany’s citizenship law. These changes improved access to naturalisation, particularly for those born in the country to foreign parents. Put simply, there is an ongoing conflict about whether commonality is a necessary foundation of shared citizenship and, if so, what types of things citizens should have in common. Should they share a commitment to basic liberal rights or practice similar traditions and customs? The debate reveals clearly that what ‘being German’ means is contested.

Employing a discursive survey design, I asked 300 German citizens to define what citizenship meant to them. Participants used 24 statements to construct their own definitions of citizenship. They could decide which statements to use for their definitions, and whether to endorse or reject the statements.

I then grouped together participants with similar response patterns into distinct but relatively encompassing perspectives on citizenship. The results feature in my open-access journal article. Its analysis shows that citizens' perspectives mirror the conflictual public debate on citizenship in Germany.

Four distinct perspectives emerge from the survey. Citizenship revolves around culture and common life for ethnocultural citizens and around democratic institutions and participation for active citizens. Citizenship means democratic institutions and individual self-sufficiency for liberal citizens. For cosmopolitan citizens, it means attachment to universal rights and humanist connection.

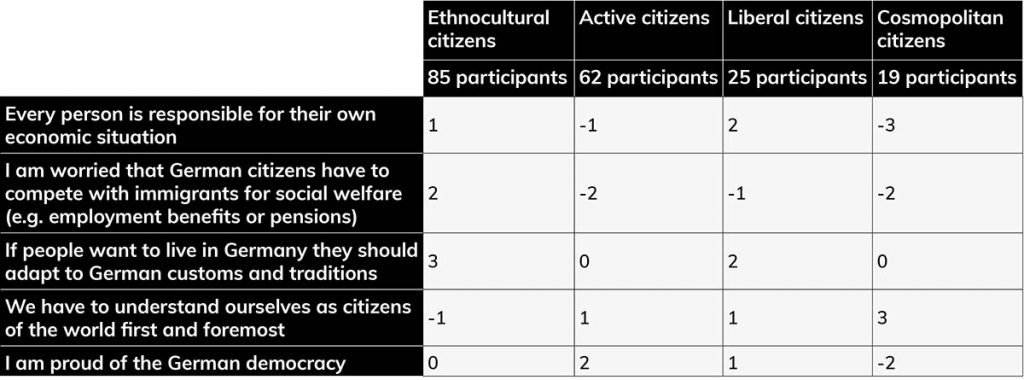

The perspectives entail fundamental differences in understandings of governance, culture, and social justice. The table below illustrates some of my survey's most controversial statements.

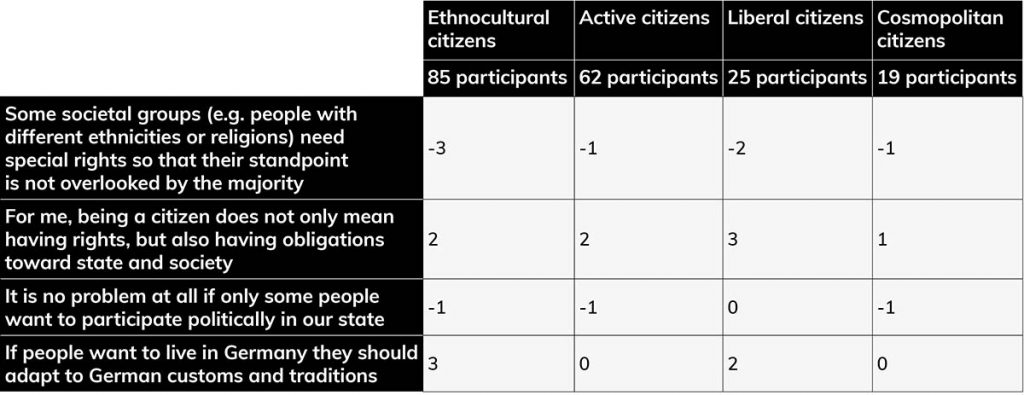

We can identify common tendencies between these perspectives, some of which I summarise in the table below. In particular, all four groups understand citizenship as being more than a legal status. Something shared between citizens is attached to all perspectives. This may be through thick conceptions of shared ancestry, active participation, thin conceptions of shared institutions, or a humanist connection.

Across perspectives, citizenship comprises not only rights but also obligations. Obligations lie in contributing to and upholding those connections. Civic engagement is an integral part of citizenship for all perspectives. Three of the four groups think it is unacceptable if not all citizens participate politically.

There are also some common tendencies on justice and culture. None of the perspectives fully endorse minority rights, like special exemptions for cultural or religious groups to ensure their representation in politics and society. Additionally, ethnocultural and liberal citizens favour assimilation by immigrants. Active and cosmopolitan citizens favour a more open, inclusive conception of citizenship. However, these citizens do not necessarily oppose assimilation.

The abovementioned similarities and differences highlight that commonality is indeed important for citizenship. However, the content of these commonalities is contested. Though cultural aspects are important to ethnocultural citizens, the three remaining perspectives have a high commitment to universal rights.

While ethnocultural citizens reject humanist connections across borders, supporters of the other three perspectives see themselves as citizens of the world. There is a general notion of feeling responsible for or belonging to a space beyond the nation-state.

Proponents of what I call the cosmopolitan perspective embrace a cosmopolitanism based on securing global universal rights, individual freedoms, and mobility. These participants feel low attachment to German culture, traditions, and democratic institutions. However, they do not advocate deepening EU integration. This indicates that the cosmopolitan perspectives I find in this survey place greater emphasis on individual-level than institutionalised solutions for achieving global connectedness.

My study's discursive, bottom-up approach, brings nuance to our understanding of citizenship. Citizens themselves can help us identify sub-aspects of citizenship that analysts should consider relevant.

Because this survey measures subjective perspectives, it is not representative of the German population. Rather, it offers insight into the complexities of what citizenship can mean to people, and how sub-aspects of citizenship are interconnected.

These results tap into a longstanding conflict between commonality and pluralism in modern conceptions of citizenship. In applying these results in policy and practice, we must devise ways for citizens to feel connected to a common project in a civic frame.

Citizens themselves have different ideas on how to create such connectivity. These range from thick political participation to a thinner but tangible dedication to institutions. It seems useful to bring these perspectives into conversation with each other to seek out commonalities, compromises, and conflicts.

Developing ideas for public spaces or common practices could therefore be a useful starting point to make a unifying experience of citizenship possible in pluralistic societies.

This blog draws on research presented in Franziska's recent Political Research Exchange article, Citizenship from Below: Exploring Subjective Perspectives on German Citizenship