A right-wing coalition won the Italian general election in September, but not all the parties within it fared well. After a boom in votes in 2018–19, support for Salvini’s League has collapsed. This, argue Arianna Giovannini and Davide Vampa, is the price for selling the party’s soul

The League (Lega) is one of the oldest parties currently active in Italy. However, in recent years, it has undergone a profound transformation from a regionalist party ‘of the North’, to a nationalist nativist one. Matteo Salvini, the party's most recent leader, spearheaded this process. It resulted in success for him, and for his party.

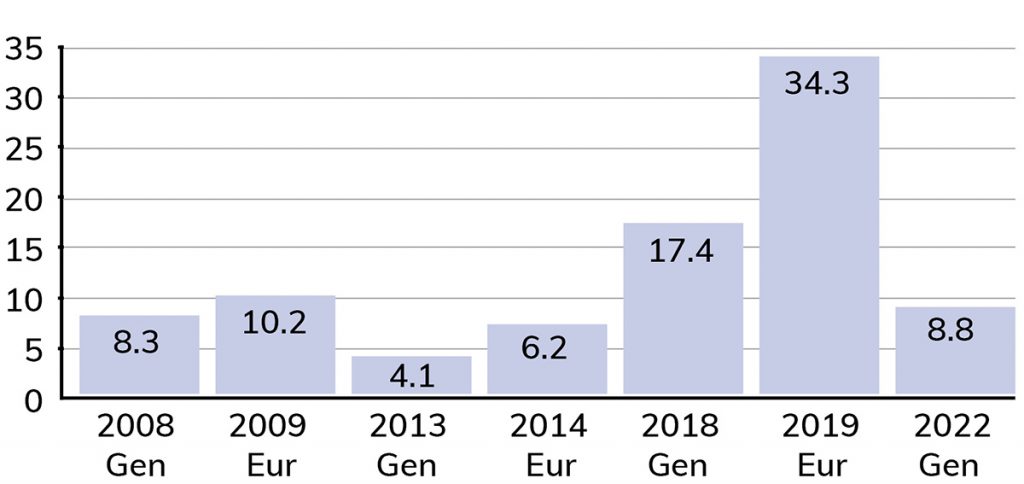

But the personalisation and nationalisation of the League essentially changed its ideological soul. In particular, this process brought in the risk of alienating the party's regionalist old guard, especially in its Northern strongholds. For a while, however, electoral success was the glue that held different currents of the party together. At the 2018 general election, the League gained 17.4% of the vote. At the following year's European election, they emerged as the largest Italian party, with a stunning 34.3%.

In 2019 Salvini’s party won almost a quarter of the votes in the South. This constituted a historic result for an organisation that for years had not spared criticism (or even insults) towards southern Italians. Italy had thus become (once again) a political laboratory in Europe. For the first time, a regionalist movement had asserted itself on a national scale. The populist chamaeleon Salvini seemed able to transpose the old struggle of the North against Rome to a new European level. Now, the whole of Italy had become a political entity seeking emancipation from Brussels.

Over recent years, the Lega has transformed from a regionalist party of the North into a nationalist nativist one

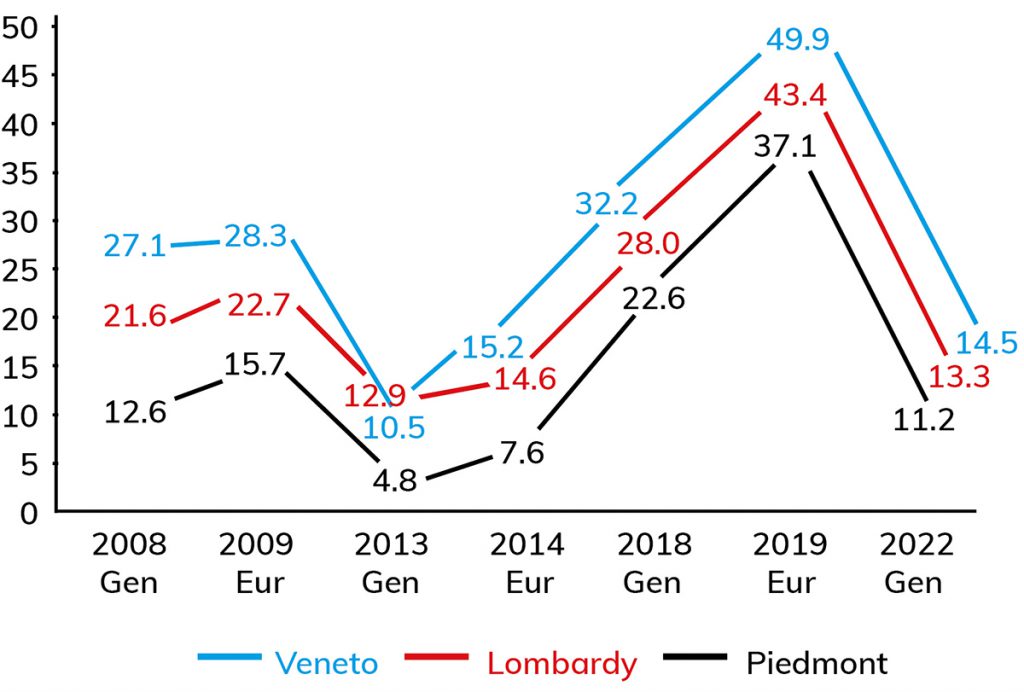

Three years later, Salvini is picking up the rubble of a political project that crashed from the dizzy heights of sudden success. The League has now returned to being a marginal player in the South, surpassed even by Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. But it has also collapsed in the North. In 2018 the Lega was the largest party in 28 Northern provinces. Now even in its traditional strongholds like Lombardy and Veneto, the party is not only far behind its 2018 results, but also below those of 2008. In 2022, it is perilously close to the disastrous performance of 2013, when it was on the brink of extinction.

From North to South, the League has been overtaken by its right-wing ally/competitor, Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia, FdI). This indicates a clear transfer of support between radical-right populists. However, unlike the League, Giorgia Meloni’s FdI has never strayed far from its core principles.

Salvini’s ‘nationalist turn’ was meant to lay solid foundations for a new sovereignist party. Instead, it ended up compromising the credibility of the Lega, because Salvini failed to capitalise on the 2018–9 success.

After trying to force an early election, Salvini was ousted from the government with the 5-Star Movement. During the pandemic, he was relegated to opposition, and he returned to power only to join a grand-coalition government led by Mario Draghi. In another twist, the chamaeleon Salvini, who had even organised a ‘Dump the Euro’ tour around Italy in 2014, became one of the main supporters of the European Central Bank’s former president.

But while Salvini focused on building a nationalist-sovereignist movement, in the northern regions the League remained under the control of more pragmatic leaders. These are actors close to the business sector, who never fully forgot the regional(ist) roots of the party. Thus, they care more about territorial autonomy than Eurosceptic nationalist campaigns.

Despite having campaigned in 2014 to 'Dump the Euro', Salvini became a staunch supporter of Mario Draghi – a former president of the European Central Bank

Eventually, Salvini ended up caught between the attempts of the party’s old guard to reassert itself and the contradictions of his approach in and out of government. This tarnished the League's image, opening a political vacuum that FdI quickly filled. Ideological coherence, an unwavering opposition to Draghi’s government, and Meloni’s leadership and communication skills helped FdI attract support from many right-wing voters who had turned to the League in previous elections.

Salvini is clinging to the helm. But the League’s internal cohesion, and its role in the new government, will likely be tested over the coming months.

Some are now calling for a Congress to redefine the party line and recalibrate the weight of its different currents. Meanwhile, longstanding activists in the North want a proper ‘reckoning’. They claim that Salvini’s nationalist turn has abjured the League's core values, and should be reversed. League founder Umberto Bossi has even called for the creation a ‘regionalist faction’ within the party, to bring it back to its roots and regain support in the North.

Though regional autonomy could avoid revolts within party ranks, it is fundamentally irreconcilable with the new right-wing government's national(ist) agenda

Short of electoral success, Salvini’s biggest challenge could now come from core regions like Veneto where, after a successful regional referendum in 2017, local leaders are still pushing for greater decision-making powers, and for fiscal autonomy. This leaves Salvini between a rock and a hard place. Regional autonomy seems key to avoid revolts within the party ranks, but is also fundamentally irreconcilable with the national(ist) agenda of the new right-wing government led by FdI.

To ride out the storm and survive, the League urgently needs to find a new identity for itself in a political space dominated by Meloni. What remains unclear is whether and how it will achieve this. Should the League challenge FdI on its own ground? Or should it diversify its political offer and return to regionalism?

This is not the first time the League has had to redefine its strategy after election defeat. But with the failure of Salvini’s radical experiment, the soul of an entire political community is now at stake. Years of twists and turns have strained the ideological-programmatic core of the party. To restore trust among disoriented (and disappointed) voters and activists, the League might now need a new leader – as well as a more coherent identity.