Vox has grown to become the third-largest political party in Spain. Its success means the country can no longer claim to be untouched by the rise of the European populist radical right, argue Andrés Santana, Lisa Zanotti, José Rama and Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte

Vox is the new Spanish populist radical right party, and the third-largest party in the country. Back when it was founded in 2013, however, Vox failed to garner much support. In the Spanish general elections of 2015 and 2016, it attracted only 0.2% of the vote.

Vox's period in the electoral wilderness came to an end in 2018. In that year's regional elections in Andalusia (Spain’s most populous region), the party took home some 11% of the popular vote. Today, Vox boasts 52 MPs in the Spanish Congress, three senators, four members of the European Parliament, 55 regional parliamentarians, 526 local councillors, and five mayors. Vox plays an important ‘kingmaker’ role, and has been an important external supporter of several regional and local governments.

Where other parties of a radical and extreme right flavour previously failed, Vox has succeeded. In so doing, it brings to an end Spain’s exceptional status as a country free of the populist radical right.

It might be said that Vox was born either at the wrong time or in the wrong place. In late 2013, the winds of change sweeping through Europe’s party systems had not yet reached Spain. On the contrary, these were the years in which the mainstream right-wing People's Party (PP), was at the peak of its powers. Between 2014 and 2017, Vox did not even attempt to run in eight of the 24 electoral contests. Where it did, it attracted only marginal support.

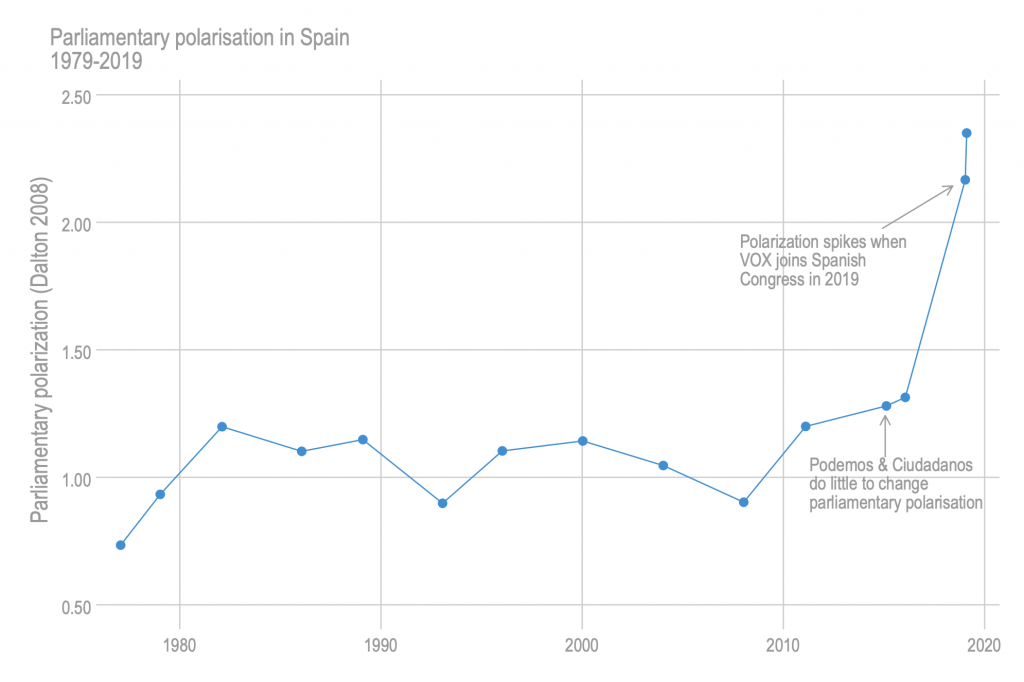

While a window of opportunity for new parties did open, leading to rise of the populist left-wing Unidas Podemos [United We Can] and the self-styled liberals Ciudadanos [Citizens], structures were not in place for a far-right party to make inroads into the evolving party system.

Vox joined the lawsuit against the Catalan leaders, presenting itself as the most reliable political actor in defence of Spanish territorial integrity

In late 2017 and early 2018, however, everything changed. Territorial tensions between Catalan nationalists (turned successionist) and the Spanish state culminated in an unlawful plebiscite and an unconstitutional unilateral declaration of independence. Vox played its cards well, joining the lawsuit against the Catalan leaders. The party presented itself as the most reliable political actor in defence of Spanish territorial integrity.

The central tenets of Vox’s manifesto are anti-immigration measures, ‘law and order’, the defence of Spanish nationalism, and traditional conservatism. It purports to defend traditional and religious moral values against what it terms a 'progressive dictatorship'. Vox falls back on an antagonistic and populist style of discourse that is fuelling affective polarisation in Spain.

You don't become the third largest party in Spain without considerable support. Vox is an electoral machine that boasts more than 54,000 affiliated party members. In the last election it gained over 3.6 million votes, or 15% of the electorate.

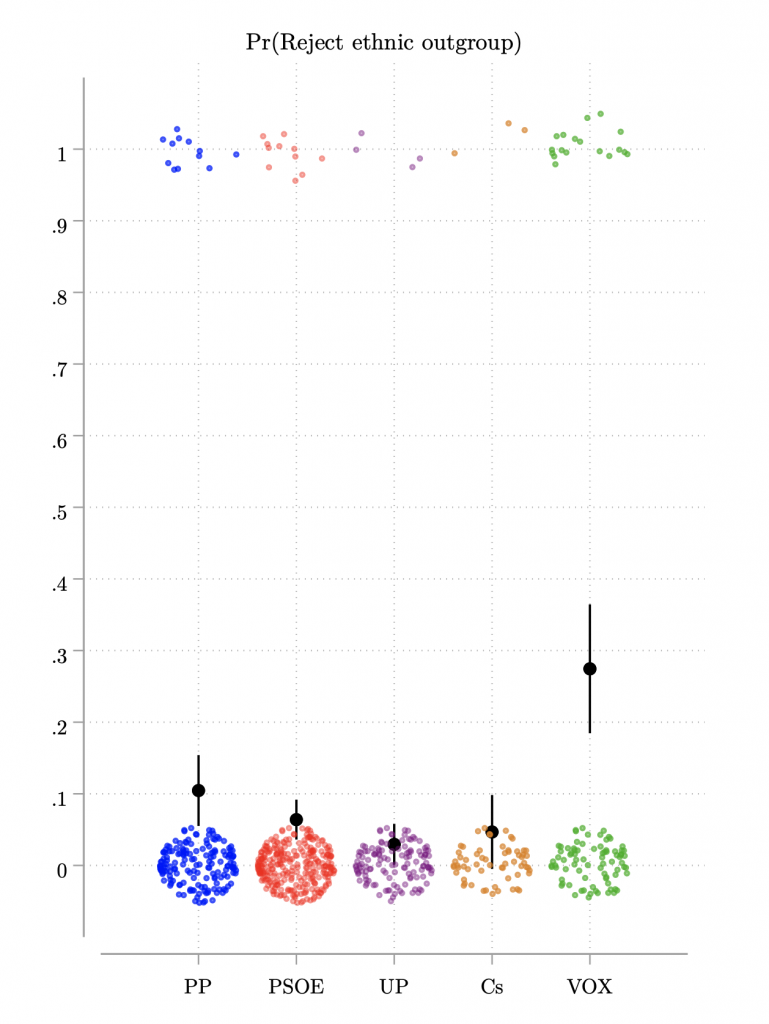

Vox voters largely conform to the 'typical' European populist radical right-wing voter profile. They are, on average, flag-waving, eurosceptic, anti-immigration nativists. They are markedly right wing, highly clustered around those who identify strongly with Spain and who see the country as 'under attack'. Supporters of Vox are significantly more inclined to oppose Spain’s EU membership, and substantially more opposed to immigration than supporters of all other parties.

Vox voters are, on average, flag-waving, eurosceptic, anti-immigration nativists

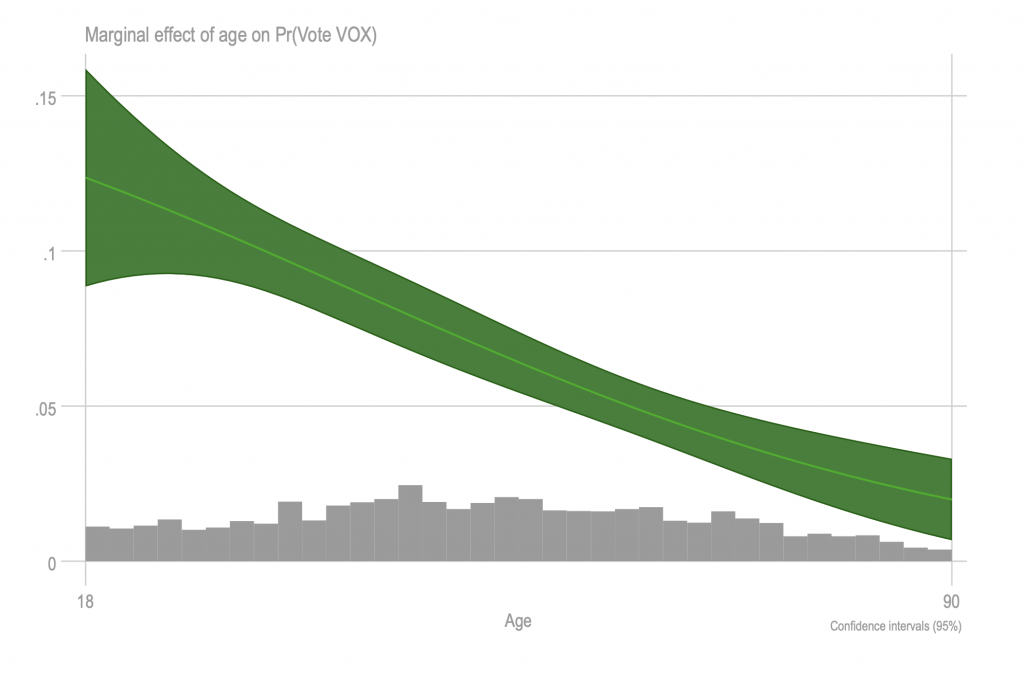

Vox voters are less inclined to believe that immigration is good for the country. They are less disposed to allow immigrants from poorer countries in Spain, and less pro-EU integration. They are more opposed to same-sex marriage, and more supportive of growth versus employment than other parties' supporters. Vox’s electorate also fits populist radical right parties’ sociodemographic profile: its voters tend to be young, male, and less educated.

Nonetheless, Vox supporters tend to diverge from traditional populist right-wing supporters, in substantive ways. Far from appealing to the so-called losers of globalisation, Vox is the party of Spain’s wealthy. Its supporters are, on average, better off than the median citizen and its voters tend to care deeply about status and wealth.

Vox is the party of Spain’s wealthy. Its typical voter belongs to the urban elite

Contrary to previous findings, Vox support is not stronger in rural areas. The typical Vox voter belongs to the urban elite.

We define Vox as a populist radical right party. The party is ideologically radical but not extreme, since discursively it does not go against the central tenets of democracy. However, belonging to the populist radical right family means that the party advocates policies somewhat at odds with several core principles of liberal democracy. These include the rule of law and the rights of minorities. Compared with the other main Spanish parties, Vox has the largest share of supporters who are dissatisfied with democracy and who do not support democracy at all.

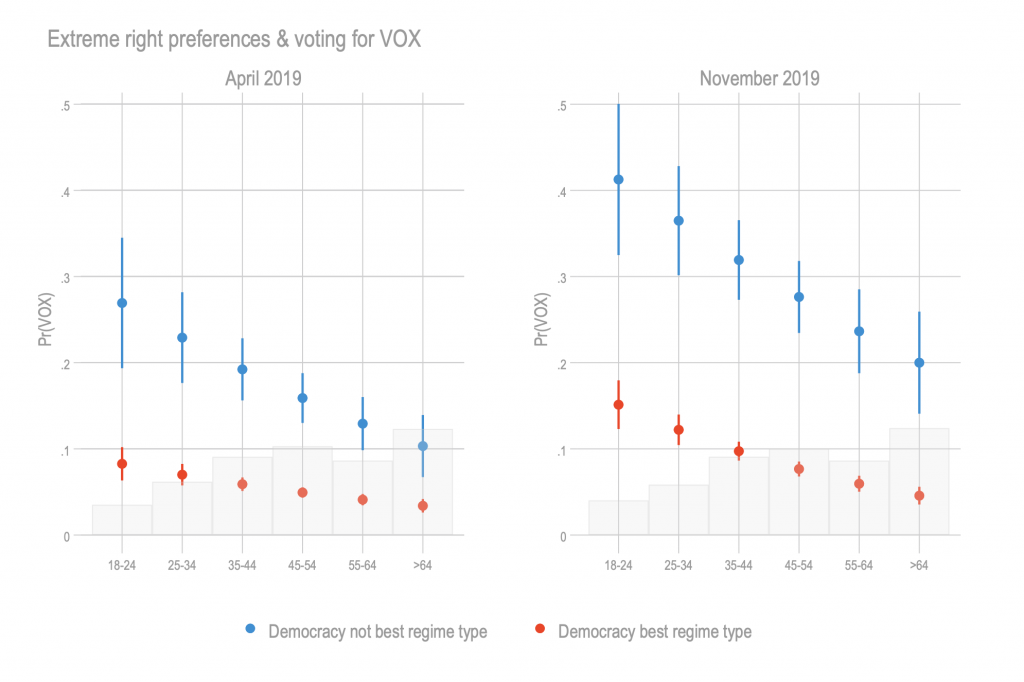

We find that support for democracy as a system of governance, and satisfaction with its functioning, significantly decrease a person's propensity to vote for Vox. This flirtation with non-democratic regime types is not just the product of nostalgic reflections among older cohorts who may cling to a romanticised image of pre-democratic Spain (alluded to in Vox discourse). It is also sizeable and notable among the party’s younger supporters.

Pundits often point to increased liberal attitudes of the young as a sign of the future health and longevity of democracies. With Vox ascendant among young voters, placing faith in the hope that the young will inherit the Earth does not project a positive picture of Spain’s democratic future.