Veronica Anghel and Erik Jones redefine the EU as a (selective membership) system of common resource pools. This, they argue, is the only way to understand its transformation under the pressure to enlarge. Enlargement means less exclusivity, so the key is to understand how the ‘goods’ that it provides are affected

Most scholars analyse international organisations as clubs. This view does not capture the evolution of the goods that international organisations generate and administer. And it does not tell us what happens when a selective membership organisation enlarges beyond its optimal club size. What if selective membership organisations shed the characteristics of a club once they become less exclusive and more rivalrous, and tighten their governance arrangements?

Our contention is that selective membership organisations shift from being clubs to being systems of common resource pools to deal with free-riding, congestion and heterogeneity. This is how international organisations avoid the tragedy of the commons.

Non-member non-state actors with access to the goods the EU generates (which we define as commons) act in their own interest and, without the constraints of membership, can contribute to resource depletion.

At the same time, member states have to deal with rivalry over the limited goods they generate and administer. This logic applies to macroeconomic policy coordination and financial market integration.

As with all managers of common resource pools, the EU must take great care not to exhaust its own resources. The risk of exhaustion usually derives from expansion, congestion, and rivalry over the resources the EU generates.

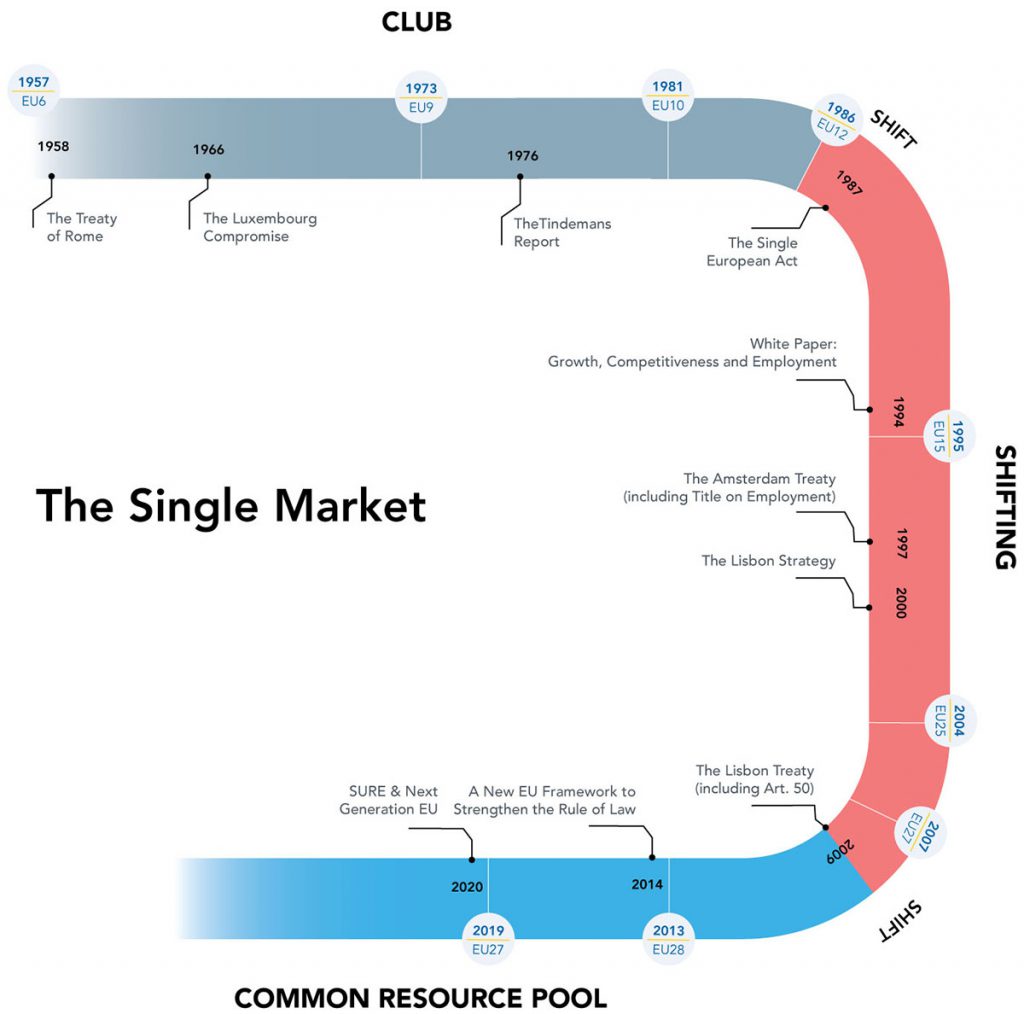

Increased rivalry over the goods the EU produces, combined with the pressure to widen, can lower the quality or amount of those goods. We traced this evolution by looking at three fundamental EU economic goods: the single market, the single currency, and the single financial space. Key documents and different exogeneous pressure points, including those associated with enlargement, show the transformation of these goods from club goods to common resource pools.

This timeline illustrates the evolution of the single market away from its club-like features. To protect the way they do business, treat workers, and safeguard the environment, Europeans wrote rules for access and enforced those rules. The European Economic Community that began with the Treaty of Rome in 1958 was a project of negative integration, removing tariffs and quotas that inhibited trade and then accompanying that with the development of a common external commercial policy. The single market looks very different today.

The EU needs to undergo internal reforms to strengthen self-discipline and multilateral surveillance among the Member States. Integrating new countries into its coordinated system of common resource pools in the absence of such constraining reforms creates the conditions for a tragedy of the commons, and a collapse of the EU system.

The EU is also a generator and keeper of non-economic goods, such as the rule of law. But EU Member States with different understandings of how to govern this resource can change its nature, thus depleting the original good and generating another (less liberal) one.

As the EU moves towards more enlargement, a major target for EU policy makers is to avoid the depletion of its attractive resources, including the rule of law

As the EU moves towards more enlargement in the context of the Russia-Ukraine war, a major target for EU policy makers is to avoid the depletion of its attractive resources, including the rule of law. That strategy includes a more accurate assessment of the state of democratisation in a candidate country.

We already know that democracy is not possible without democrats. Yet, in terms of the criteria for enlargement, why do we focus so much attention on political institutional design?

Take, for example, the case of Hungary during its accession process in the last phase of EU enlargement. There was ample evidence that Hungarian democracy was already failing. These signals, moreover, we can trace back to the early 1990s. As Hungary was preparing for EU membership, many of the fundamental problems of Hungarian elites’ commitment to democracy were overlooked. The problem is that the criteria for acceptance had little or nothing to do with the forces undermining Hungarian democracy.

Learning from these and other lessons of the past, the EU must update its assessment indexes for members and candidate states, avoiding an overreliance on formal measures. The experience of enlargement to Hungary highlights the risks of overestimating a country’s democratic credentials.

The EU's current approach to assessing Ukraine and Moldova's democratic reforms provides a hopeful step in a more nuanced direction

The EU's current approach to assessing Ukraine and Moldova's democratic reforms provides a hopeful step in a more nuanced direction. Both countries are expected to make significant democratic and rule of law improvements. Notably, the EU is evaluating Ukraine's democratic rule of law even amid martial law, challenging decision-makers and technocrats to rethink how democratisation processes occur.

The dynamics of common resource pools are also useful to stress-test EU institutions for failure. If Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, and the countries of the Western Balkans are left out of Europe and undefended from third-party attempts at destabilisation, the people in those countries will not become more democratic. If anything, they are likely to move in the opposite direction under Chinese, Russian or other foreign influence.

At the same time, more and more people from countries outside the EU are going to have to seek refuge in the European Union. More and more of their firms will rely on access to Europe for their success, and those firms are going to be more and more resistant to European regulation or influence. Worse, the security conditions in those countries will deteriorate, and that means European security will also diminish.

Enlargement offers an opportunity for the EU to exercise control over its borders. Despite its reluctance to enlarge, the fact is that European integration was a model to deal with instability in the past. It could be so again.