More than a third of all protest events in Bulgaria and Slovenia since the Great Recession have been class-based. Workers’ mobilisations show durability, contends Ivaylo Dinev, though differences between sectors continue to exist

Since the 1960s, social movement studies have shifted away from a focus on class and labour mobilisations. That focus moved to environmental issues, then to human rights, and on to oppression based on gender, race, and ethnicity. However, the Great Recession of 2008 triggered global waves of protest. As a result, we have seen a resurgence of interest in economic threats and the role played by varieties of capitalism in explaining people's discontent.

In times of deepening inequality and intense political conflict, it is important to understand who is protesting, and how class politics matters. In a recent article, I show that class remains a key driver for protest mobilisation.

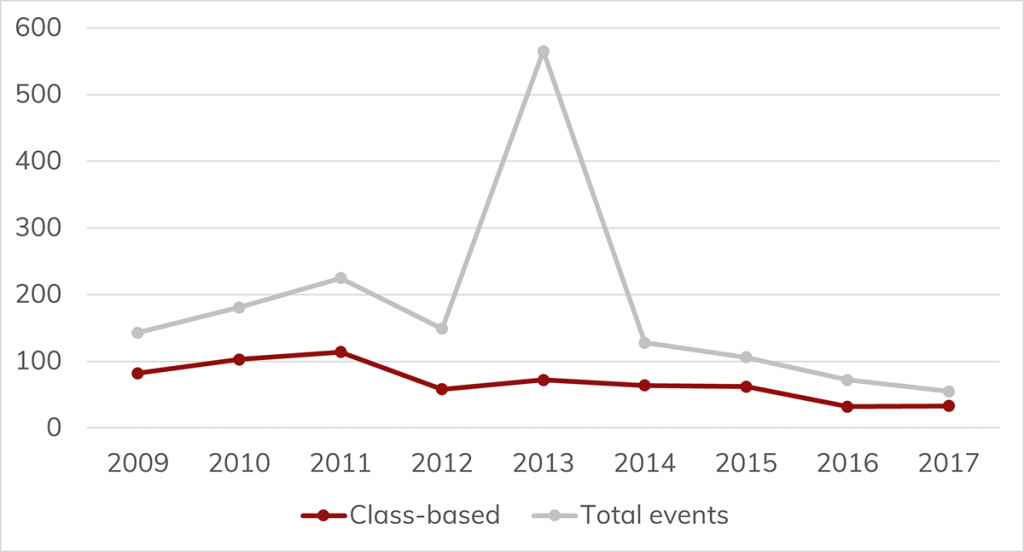

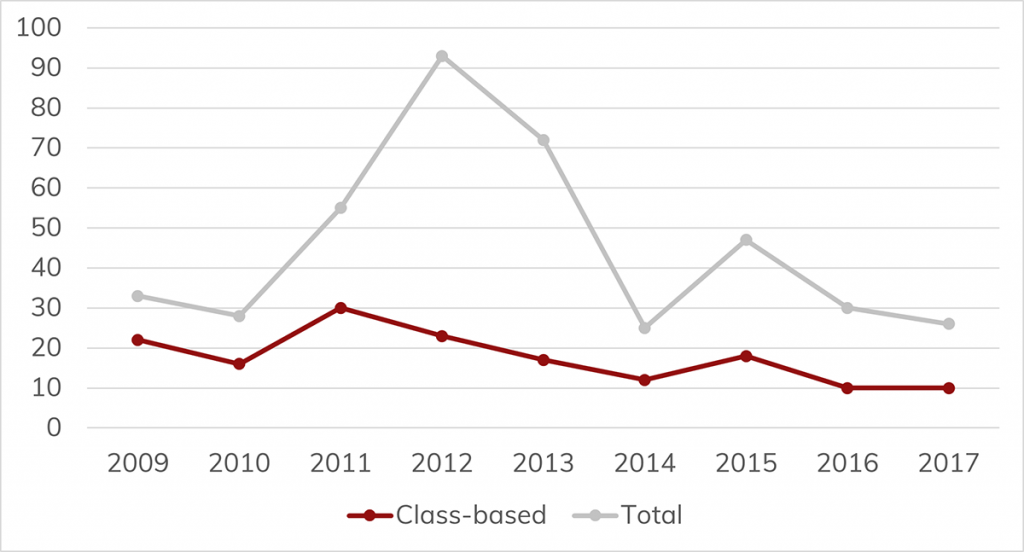

The original Bulgaria and Slovenia protest event dataset, built upon news retrieved from national press agencies, shows high frequency of class-based protest events in both countries over the period between 2009 and 2017. Specific class actors drove 38.2% of all events in Bulgaria and 38.6% of all events in Slovenia.

This challenges the popular opinion that class is disappearing. However, it does seem that class-based events have quite different dynamics to general dissent. Protest events spiked during the anti-governmental protest waves in 2012–2013. Class-based mobilisations, on the other hand, remained at similar levels to previous years.

People organised via Facebook, without strong ties to traditional organisations such as trade unions, interest groups and political parties

There are two reasons behind this. Massive discontent among informal groups was at the root of these waves of protest in Bulgaria and Slovenia. People organised via Facebook, without strong ties to traditional organisations such as trade unions, interest groups and political parties, and labelling themselves 'the people' or 'the citizens'. Thus, these waves appear to be either classless or built upon inter-class coalitions.

Meanwhile, over the longer term, class-based contention shows durability through mobilisations of trade unions and unorganised workers' collectives.

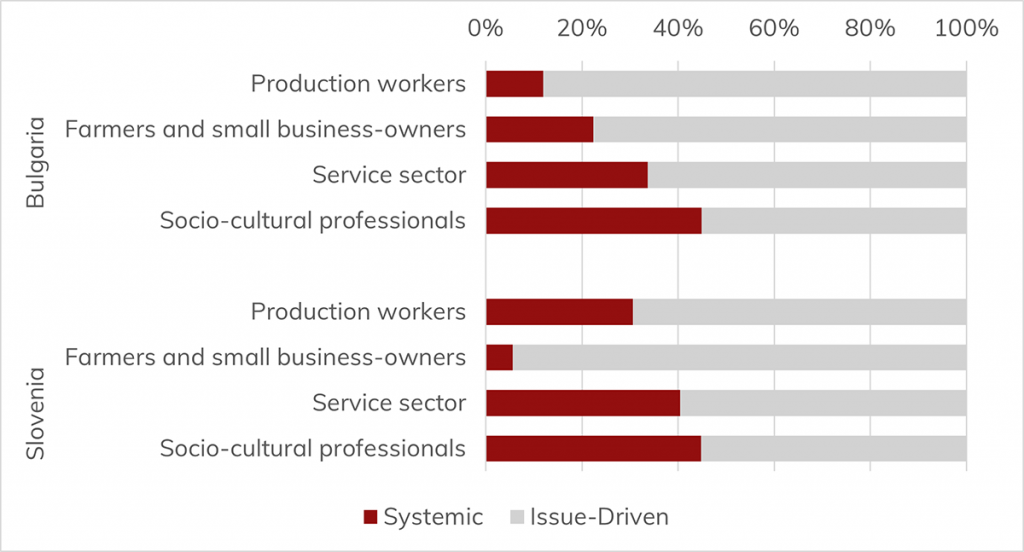

I use two axes to explore the protest dynamics of diverse social classes. The first is a dichotomy between workers and 'independents' (farmers, small business owners, major employers – the capitalist class and the petit bourgeoisie). The second distinguishes between the socio-cultural, service, and production sectors.

The majority of media reporting focused on working class collective actions, as opposed to the few activities led by the 'independent' groups. In Bulgaria, workers mobilised for 428 of the 620 class-based protests. In Slovenia, workers accounted for 139 of 158 such protests.

the working classes were at the root of the major economic conflicts, particularly during the initial period of austerity

These Marxist class categories reveal that the working-class population was at the root of the major economic conflicts. This is especially notable during the initial austerity measures between 2009 and 2012. However, internal variations among workers within occupations and sectors continue to exist.

News sources are unable to provide information on the variety of protesters' professions. They usually describe such people as workers/employees in a specific factory or public sector, but this fails to distinguish between more complex social class categories. As a result, sources often merge clerks, technical specialists, and higher-level administrations into the same category. However, we can still draw some conclusions.

During the observed period, neoliberal austerity measures were implemented in the public sector, with budget cuts in education and healthcare. Workers in the private sector, meanwhile, suffered job cuts and unpaid wages.

Production workers usually addressed grievances about pay and conditions towards the company owner or the government

It seems that socio-cultural professionals and workers in the service sector were behind most of the protests in Slovenia and Bulgaria making 'systemic' claims. The production and agricultural sectors, meanwhile, experienced the lowest level of systemic protest. Production workers usually addressed their grievances about pay and working conditions towards the company owner or the government.

Class-based mobilisation has not disappeared from European politics. Working class organisation and trade unions mobilise a large proportion of protest, especially during periods of growing economic threats and austerity measures.

In the future, class conflicts may intensify. Right now, such conflicts are being blurred by the multi-layered Covid-19 crisis along with large-scale transformation towards the green economy and digital capitalism.

Analysing the dynamics of protest mobilisation with a focus on class politics can help us understand the effects of the current crisis, and what we can expect in the decades to come.