To understand the storming of the US Capitol, we must consider its possible roots in economic inequality. This, along with economic elites' ability to transform material wealth into political clout, has contributed to record political polarisation in the US today, writes Alberto Parmigiani

After the furore of the event itself, and its political repercussions, the storming of the Capitol building on 6 January has receded from front page news. It is now left to social scientists to ponder the causes.

Scars in our collective imagination are a compelling motivation to dig into the event's many facets. These include factors long at work in American society concerning economic inequality and the influence of the ultra-rich.

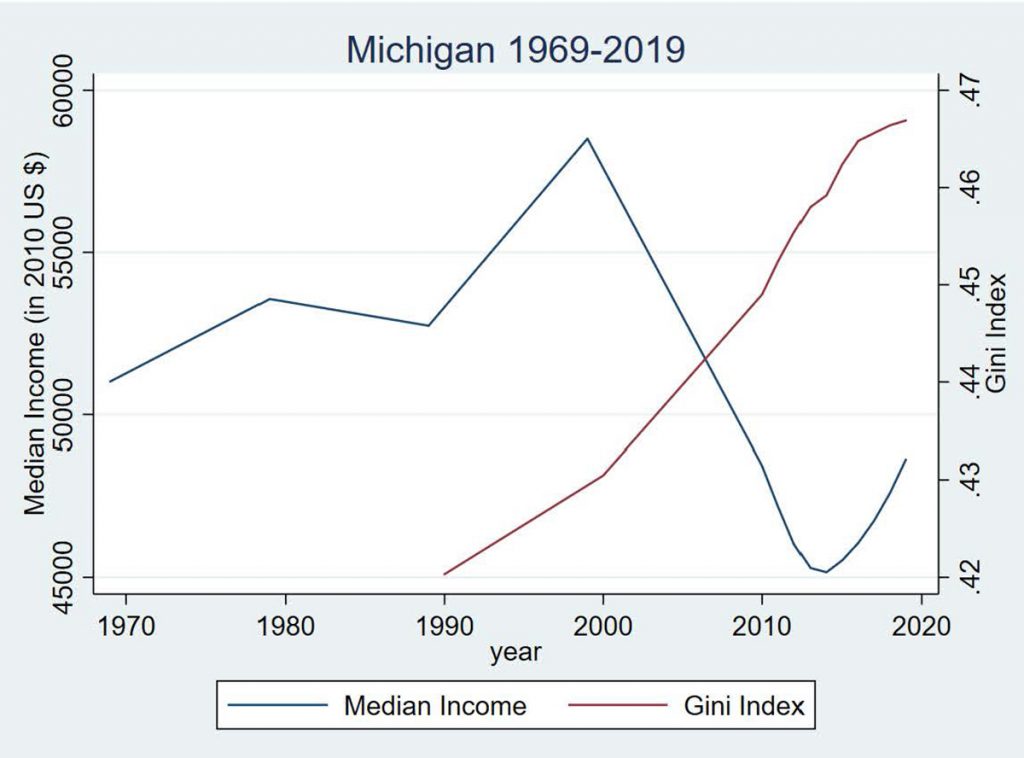

The graph below displays two variables: household median income in real terms (left scale, blue), and Gini index of economic inequality (right scale, red), in Michigan, the state hardest hit by the 2008 economic crisis. Despite a recovery over the last few years, real median income in 2019 is still lower than in 1969.

Michigan is an extreme example, but the trend is similar in the rest of the country.

In thirty out of fifty states, household median income in 2019 is smaller than in 1999. Over these two decades, inequality has increased in all fifty states, from already high levels relative to other Western countries.

Between 1999 and 2019, inequality has increased in all fifty US states

In New York, Florida and California, by contrast, the median income growth rate has been remarkable. But inequality in these three states is among the highest in the country, and the index has risen during this period. This means that when economic recovery did happen, it was the exclusive prerogative of the richest class.

In the majority of states, though, median income has decreased, and inequality has increased.

Polls in the aftermath of the event showed almost half of Republican voters, and around a fifth of the entire electorate, supported the storming of the Capitol. Months later, 60–75% of Republican voters, and around a third of the total electorate, still believe the presidential elections were rigged.

Polls in the aftermath of the event showed around a fifth of the entire electorate supported the storming of the Capitol

Extreme polarisation of the American electorate, especially the Republican Party's shift to the right, began in the late 1970s. At that time, a political offensive by wealthy elites pursued change to the Trente Glorieuses (1945–75) economic model. On the one hand, they founded a cultural network of foundations and think tanks to influence public opinion. On the other, they expanded their political power, most importantly through campaign contributions. This two-faceted strategy becomes especially relevant given that these groups tend to be more pro-market than the general population.

The current debate undervalues the political dedication of business groups and wealthy families. Such groups have, over the years, founded and supported a cultural network promoting their economic interests.

Members of institutes and foundations are frequent guests on news programmes and talk shows, often interviewed as impartial experts. These foundations publicise policy briefs and produce allegedly neutral simulations of policy interventions. Such power groups have an extreme laissez-faire ideology, opposing any state intervention. They have aimed at a clear cultural hegemony – arguably, for many years, with success.

At the same time, political finance regulation in the United States is very limited, leaving room for policy influence. The concentration of contributions has increased massively in the last decades, as figure 5 here shows.

political finance regulation in the United States is very limited, leaving ample room for policy influence

More generally, interest groups can easily donate to parties and congressional candidates without limits. In this way, they distort the usual mechanisms of political representation so that legislators often depend more on big donors than on their broad electoral constituency.

The most relevant example of this power network is that of the Koch brothers, who brilliantly adopted both strategies.

Between 1977 and 1980, Charles and David Koch founded three foundations, still prestigious today. They believed in the power of ideas and the importance of agenda-setting to influence public opinion, beginning with university students. The Kochs concentrated not on the immediate future but looked for medium- to long-term influence, beyond the next elections.

Expanding in the 1980s and 1990s, the network completed its definitive transformation in 2003 and 2004, founding Koch seminars for far-right donors. The network also launched Americans for Prosperity, arguably the most important political organisation in the US after the two main parties.

Koch seminars are biannual conventions of hundreds of donors. The seminars raise money through political action committees that can donate limitless amounts to candidates with the same ideological principles.

Koch seminars raise money that can donate limitless amounts to candidates with the same ideological principles

Americans for Prosperity instead works as a party-inside-the-party. It drafts model bills and leads legislative battles in all states, against policies such as Obamacare. Its stated purpose is to shift the Republican Party to the right on economic matters, weakening the power of the unions and resisting growth of public expenditure, let alone taxation.

We could say, at a stretch, that the purpose of Americans for Prosperity is to increase inequality.

This network has been highly successful over the years. From the local to the federal government, the Republican Party represents these groups more accurately than the population at large – or even Republican voters. This explains, at least partially, why political decisions do not reflect the preferences of the majority of citizens.

The US is experiencing record levels of economic inequality. At the same time, its regulation of political finance is lax in the extreme. This combination offers the wealthiest elites enormous opportunity for political influence, and so distorts the incentives of democratic representation.

To understand extreme political polarisation, and how a violent mob came to storm the US Capitol, we must consider the growing ability of the ultra-rich to transform their wealth into political power.