The inclusion of social minorities is contingent on civic activism and government policies that become more polarised and volatile in times of crises. Markus Thiel, Ernesto Fiocchetto and Jeffrey Maslanik delve into the state of inclusion policies throughout Europe

Over the past two decades, the EU and most of its governments have made efforts to safeguard the equality and socio-economic inclusion of their residents. Success rates have varied. Recent elections, combined with widespread insecurity, have put issues related to inclusion and exclusion at the centre of politics. This is especially true with regard to gender equality, LGBT+ rights, and the inclusion of migrants and refugees.

Hence social inclusion policies, laws and discourses vary widely in the EU. Related anti-gender / LGBT+ and migration / refugee policies range from progressive to restrictive. We can attribute the differences to the changing governments and structural contexts of different EU states.

Depending on the government and the structural context, anti-gender and anti-refugee policies across the EU range from progressive to restrictive

Aside from policy developments at national and EU levels, a number of crises have weakened societal cohesion. These range from the Euro-crisis to refugee pressures to the security crises caused by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. In fact, analysts speak of ‘permanent emergency’ and the EU’s ‘polycrisis’ to highlight the multiplicity of causal factors at work in these complex, often interlinked crises. Social in/exclusion is more strongly accentuated during these times, as more conflictive divisions emerge.

New socio-political forces do more than merely espousing protective measures by existing societal and political actors. They bring to the surface either opposition to, or enhanced opportunities for, minorities. Such cleavages often emerge because power holders fear losing existing privileges in the face of new threats and resource limitations.

In this complex scenario, how can we understand the policy improvements and setbacks regarding inclusion in European countries? What effects do the structural changes caused by crises in the EU have on socio-economic and socio-political in/exclusion of minorities? And to what extent does the rise of political mobilisation among civil society groups and parties advance minority in/exclusions in Europe?

Our comparative analysis focused on how political mobilisation has shaped inclusion laws, blocked policy progress, or advanced policy improvements

We conducted a comparative analysis of four representative case countries: Sweden, Germany, Spain and Poland. Our focus was on how political mobilisation has shaped such laws, blocked policy progress, or advanced policy improvements. We also analysed linkages and gaps between laws, politics and civic mobilisations to capture the contingent but also contradictory ways civil society and policy-makers perceive and address in/exclusions of social minorities domestically.

Our research traced the in/exclusion of women and LGBT+ people through analysis of the EU Gender Equality Index, the Rainbow Europe Map and Index and public opinion data. Country cases show that recognition of variously perceived ‘crises’ varies. While a notable opposition to inclusion has emerged throughout, different conceptualisations of risks condition the degree of in/exclusion.

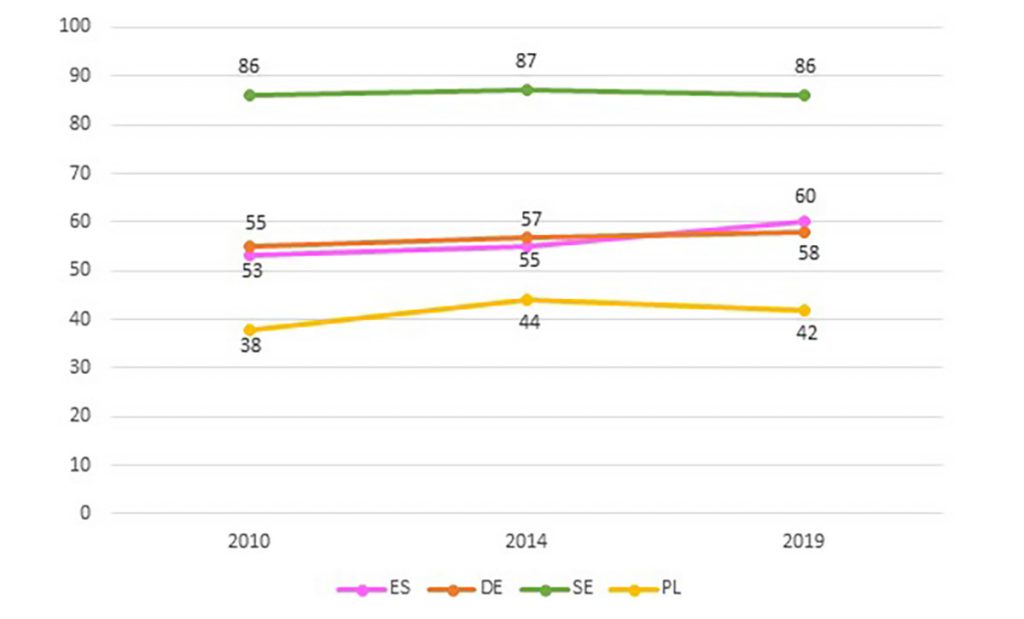

In Spain (ES), Sweden (SE), Germany (DE) and Poland (PL), gender and LGBT+ rights have become more salient and contested, albeit with diverging socio-political responses. In Spain and Sweden, meanwhile, political and civil society actors have diffused an inclusive women’s rights framework in socio-economic and political arenas. However, in Germany and particularly in Poland, such equality has been more difficult to achieve. And while progressive political mobilisation efforts have yielded varying results (see graph below), notable opposition to LGBT+ rights has also emerged.

The trans* self-determination law, for example, passed through parliament in Spain despite opposition from conservative sectors. Germany is struggling to develop a similar approach. Poland's nationalist government remains reluctant to advance trans* rights. And Sweden, once a pioneer in LGBT+ rights, curbed trans* policies when the current administration came to power.

Similarly, increasing polarisation over immigration, citizenship and inclusion has emerged in EU member states, leading to racism and discrimination against refugees and migrants. This, in turn, results in lower educational attainments, lower employment rates and less political participation. In addition, far-right parties and movements across Europe have used their presence to advance exclusive-nativist positions. In contrast, progressive civil society groups aid the state in service provision for those minorities, and represent essential interlocutors co-determining their societal in/exclusion.

Based on the Migrant Integration Policy Index and public opinion data, we trace the political mobilisations and highlight some of the most prevalent trends in the four case countries. In Sweden, care with paternalistic overtones ‘for the benefit of refugees and migrants’ is prevalent. In Germany and Spain, by contrast, inclusion is ambiguously related to these countries’ illiberal histories. Polish policies, meanwhile, are based on nationalistic and/or religious doctrine. Notably, Spain and Sweden’s relatively liberal policies face uncertainty in view of their changing governments.

Our comparative analysis highlights the linkages and gaps between the EU-level formulation of policies and their domestic implementation. It also evidences the differences among member state policies. Yet it shows, too, unevenness in the various aspects of social inclusion as measured by the different indexes.

The side-by-side examination evidenced, for instance, that an increase in women’s rights can occur simultaneously with a stagnation or even decrease in LGBT+ rights, as occurred in Spain.

An increase in women’s rights can occur simultaneously with a stagnation or even decrease in LGBT+ rights

And on a more granular level, the indexes illustrate how advances in one index indicator contrast with regressions in others of the same index. This means that inclusion policies invariably lead to exclusions in other areas of private and public life, often caused by opposing socio-political forces and the prioritisation of certain objectives over others. Hence inclusion is contingent on the way in which political mobilisations based around perceived risks and threats materialise.

Finally, improved inclusion necessitates the recognition of future trends: changing demographics with increased socio-cultural diversity, geopolitical fragmentation and the management of new challenges such as the decline of democratic norms or the rise of artificial intelligence.

In all these areas, societal and political inclusions – as well as exclusions – determine the range of possible actions the EU can take to prove more cohesive, and thus resilient, in an age of insecurity.