Recent data indicates that countries led by more populist leaders are less likely to have a military with veto power. Hakkı Taş explores the populist centralisation of power that fosters control over the armed forces, and its impact on civilian oversight

The military represents a major blind spot in contemporary populism studies. Scholars tend to view populism through the prism of civilian mass politics, and to neglect the political role of the military elite.

In Latin America, ironically, classical manifestations of populism emerged from military authoritarian regimes during the 1930s and 1940s. Indeed, Latin America was the focal point for pioneering studies in both populism and civil-military relations. These studies were intertwined until the region's epochal third wave of democratisation in the 1980s. During that period, the term ‘military populism’ gained currency, characterising regimes like those led by General Juan Velasco Alvarado in Peru or Getúlio Vargas in Brazil. A blend of authoritarian governance and populist economic policies shaped these political landscapes.

Seven of the top ten populist countries have witnessed at least one successful coup d’état since 1946

Today, it is imperative to bring the military back into populism studies. The Global Populism Database shows that the armed forces remain a considerable political actor. Seven of the top ten populist countries have witnessed at least one successful coup d’état since 1946.

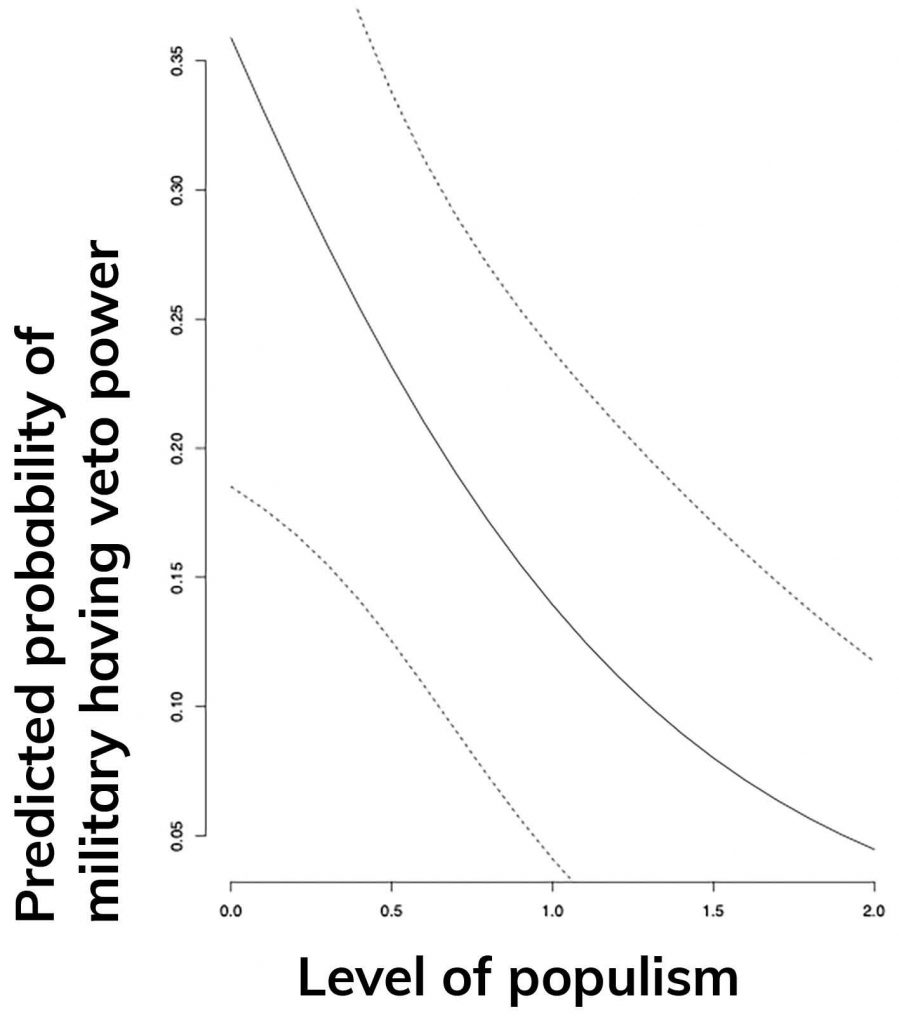

My research found that populism is conducive to the civilianisation of politics. We associate the rise of populist power with less veto power from the military; namely, a military that is less likely to interfere with or block the government's decisions. Populist leaders in military-dominated countries often clash with the powerful military establishment, fostering an anti-military sentiment among their populace.

This pattern, however, only fully manifested in Turkey (2007–2013) and Thailand (2005–2006, 2011–2014). The Turkish Kemalist regime and the Kingdom of Thailand conferred guardian status upon the military. As a result, anti-military rhetoric stemmed from the fear of military intervention. Moreover, the prospect of a coup—real or fabricated—has in the past been used as a tactic by some political leaders to rally public support. In Venezuela, populist leaders Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro propagated conspiracy theories of external plots to topple or assassinate them, and framed anti-government protests as attempts orchestrated by the US.

Despite the prevalent anti-military rhetoric used in non-Latin American countries, the alignment between populism and the military is more common in this region. Remarkably, many prominent populist figures, including Chávez in Venezuela, Lucio Gutiérrez in Ecuador, and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, boast backgrounds in the armed forces. Indeed, before they rose to power, Chávez and Gutiérrez both participated in coup attempts, in 1992 and 2000 respectively. We see an affinity between populism and the military in anti-imperialist discourse, especially when the ‘elite’ is associated primarily with an international entity.

This populist-military alliance appears contradictory in the context of the civilianisation of politics under populism. Nevertheless, the populist way is not objective civilian control of the armed forces based on civilian oversight mechanisms and military professionalism. Instead, populist civil-military arrangements stem from a distrust of institutions common to populism. This leads to a personalised concentration of executive power, which opens the door to direct control over the military. Many populist leaders politicise the military and align it with civilian spheres. They seek to establish individual, communal, or ideological connections to secure military compliance.

Many populist leaders seek to establish individual, communal, or ideological connections to secure military compliance

Populist leaders may choose to establish tight control over promotions. In Venezuela, Maduro promoted thousands of middle- and lower-ranking officers based on their personal loyalty to him. In Thailand, former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra pursued a strategy to personalise his influence over the police and military by favouring trusted circles and aligning their interests with his own. He elevated his confidants, including former classmates and close relatives, to key positions within the armed forces, thereby establishing a dedicated faction within the army loyal to him alone.

Another tangible manifestation of personalised control is the military purge. This tactic penalises disloyal or less reliable officers, and instils fear among potential contenders, reinforcing the authority of those in power.

Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, endeavoured to narrow the divide between civilians and the armed forces. Through initiatives like the Equal Opportunity Program, Morales fostered greater inclusivity of substantial indigenous communities within the armed forces.

Evo Morales' Equal Opportunity Program fostered greater inclusivity of substantial indigenous communities within Bolivia's armed forces

Similarly, in Ecuador, bolstered by indigenous support, former president Rafael Correa expanded the presence of indigenous-only units. By adjusting the criteria for admission to military academies, Correa aimed to increase the number of indigenous officers within the army ranks.

Turkey, by contrast, is a stark example of the opposite trend, purportedly marked by the removal of Alevi officers, a group widely regarded as integral to the Kemalist secular army.

The Chávez regime prized ideological loyalty above all. In so doing, the regime reshaped Venezuela's armed forces into a revolutionary entity. Enshrined in the 2008 law, the Venezuelan army was defined as anti-imperialist, revolutionary, and Bolivarian.

Similarly, Correa and Morales leveraged the military's historical leanings towards leftist anti-imperialist beliefs to forge a shared ideological platform. In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan shut down the Kemalist-oriented military schools, replacing them with the National Defence University. These are now under the full control of Erdoğan's Justice and Development Party (AKP), consolidating influence over military education.

As discussed in this Future of Populism series, populism can be a threat to and a remedy for democracy. Likewise, populist leaders can embody both militarist and anti-militarist traits. Increasing support for populist leaders grants them the capacity to either suppress, negotiate with, or deploy armed forces as needed. However, within the framework of populist institutional erosion, a precarious atmosphere emerges: the very conditions that breed populism also foster military interventions.

No.75 in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more