In March 2001, the EU agreed a directive providing temporary protection for non-EU nationals fleeing conflict. In 2022, it revived the directive to allow displaced communities in Ukraine to settle in the EU. Niruka Sanjeewani argues this undermines the EU’s human rights policies, and weakens EU efforts to create more legitimate asylum mechanisms

After Russia’s full-scale invasion, and in response to the outflow of citizens fleeing Ukraine, on 4 March 2022 the EU triggered the Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) through Council Decision 2022/382. The UN Refugee Agency predicted the invasion and subsequent war would likely create ‘Europe’s largest refugee crisis this century’.

The TPD is a key element of the EU’s Common European Asylum System (CEAS). CEAS delineates responsibilities among member countries in accommodating asylum seekers. Its Article 67 highlights the need to adopt an equal, fair, unified and harmonised approach to sharing the asylum-seeker burden.

In line with European Commission standards, the directive comes into force only if member states perceive a 'mass influx' is happening. This was the EU's first TPD activation since the Yugoslav wars in 1990.

Now that the EU has activated the TPD for Ukraine, questions arise. What constitutes a mass influx? How many people must be fleeing for the EU to consider it a mass influx? And why did the EU not implement the TPD during the recent Syrian and Afghan refugee crises?

According to TPD Article 2, paragraph 1, the following people are eligible for protection:

The TPD has allowed member states to apply temporary protection for permanent residents who were in Ukraine before 24 February and are unable to return to their countries of origin.

As per EUROSTAT, the EU granted 256,860 decisions on temporary protection during the third quarter of 2023. Compared with the second quarter of that year, the number of decisions decreased by 1.3%.

Third-country nationals who have benefited from national or international protection are covered by the EU directive. Article 20(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union defines 'third-country national' as a person who is not a citizen of the European Union and does not enjoy EU right to free movement.

In line with this, we could consider Ukrainians as third-country nationals. Yet, by adding the condition of national protection for third-country nationals, other irregular third-country nationals not registered as legitimate asylum seekers in Ukraine are excluded from the benefits of this directive. In 2022, approximately 60,900 undocumented people in Ukraine were unable to benefit from the rights offered by the TPD.

The Temporary Protection Directive has put Ukrainian nationals into an exceptional category, by offering them rights and protections that others do not enjoy

You could argue that the TPD is a showcase of asylum arrangements for a select group of asylum seekers. The TPD has put Ukrainian nationals into an exceptional category by offering them rights and protections that others do not enjoy.

The TPD laid down the minimum standards for granting protection to Ukrainians fleeing into EU member states. Member states are obliged to provide residency permits, access to accommodation, education, jobs, social welfare and medical care.

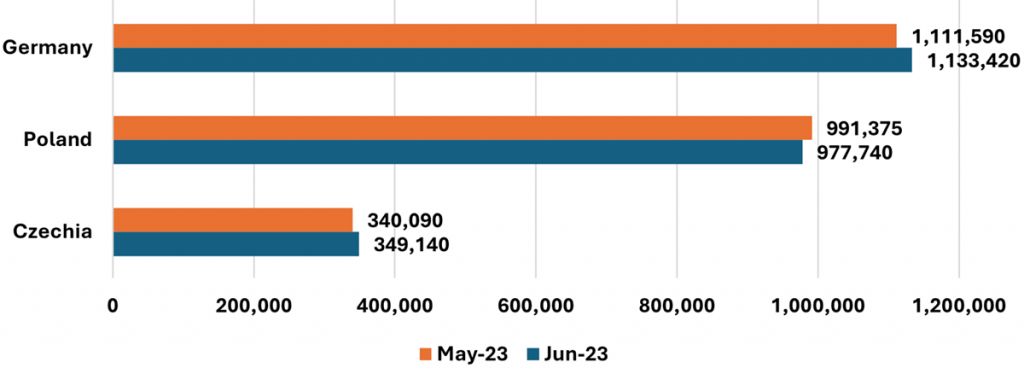

Access to accommodation has emerged as one of the most critical aspects of these support measures. There is an evident lack of political will to use reception systems in countries including Greece, Belgium, the Netherlands and Ireland. Germany, Poland and Czechia, by contrast, have sheltered the most Ukrainian asylum seekers.

EU member states are obliged to provide residency permits, access to accommodation, education, jobs, social welfare and medical care for Ukrainians fleeing the war

As the graph below shows, beneficiaries of temporary protection from Ukraine have sheltered in Germany (1,133,420 people; 28% of the total), Poland (977,740; 24%) and Czechia (349,140; 9%).

Poland welcomed around two million asylum seekers during the initial stages of the war. Contrast that country's current stance with the strong anti-refugee sentiment in 2015 against Syrian and Afghan refugees. In 2015, Warsaw refused to take in asylum seekers from Syria, and pushed against an open-door policy.

What's next? The TPD remains a temporary instrument and the EU lacks a long-lasting mechanism to deal with mass influx of migrants. As per Article 4 of the Directive, the TPD cannot extend for more than three years. This means the current regime will terminate on 4 March 2025.

Poland welcomed around two million Ukrainians in the war's early stages, yet in 2015 it refused entry to asylum seekers from Syria

Once this happens, matters related to Ukrainian asylum seekers will be governed by general procedural rules such as the Dublin regulation and the EU Qualification Directive. The Dublin regulation generally assigns responsibility to the host states to issue residency permits.

The TPD includes some unclear additional rules, shifting the responsibility to the state which has accepted the transfer of the person onto its territory (Article 18). Thus, it must clarify some grey areas on the status of asylum seekers already sheltering in the EU.

Activating the TPD in response to large-scale influx from Ukraine has undermined fundamental CEAS ideals. The TPD was designed primarily as an emergency solution, not a permanent one. Unfortunately, it has succeeded only in adding an additional tier to an already fragmented system. The EU must urgently revise its response to the Ukrainian refugee crisis – the TPD in particular.