To understand support for right-wing populist parties, we need to analyse not just voters who disengage from established parties, but also those who never voted in the first place, writes Julia Schulte-Cloos

Conventionally, the main source of support for right-wing populism is culturally conservative voters who used to support mainstream parties but now opt for the radical right because it is articulating their grievances on issues such as migration or European integration.

These voters are disengaging from mainstream parties and turning to the populist radical right, largely as a result of accelerating social change and globalisation. Such changes, argue scholars like Hooghe and Kriesi, have given rise to societal conflicts mobilised and politicised along a 'new' cultural dimension of political conflict. This dimension concerns stronger protection of national boundaries and the social status of native citizens – issues mainstream parties have largely neglected.

Yet there is a second group of voters on which right-wing populism draws, and who have been subject to much less scholarly attention to date. These voters are not disengaging from other parties; rather, they are politically so deeply disaffected as to be beyond the capture of mainstream parties.

These voters are ... politically so deeply disaffected as to be beyond the capture of mainstream parties

Dissatisfied with the political system, the offerings of established parties, and the insufficient representation of their interests, many citizens prefer not to vote at all if there's no populist party on the ballot. Scholars studying populism argue that populist parties bring back political conflict by highlighting ideological convergence among mainstream parties. In doing so, they mobilise citizens who are beyond the influence of established parties.

But does a surge in electoral turnout mean a surge in support for the populist radical right? Does more democratic participation in the electoral process result in a surge in support for anti-establishment parties? Not always.

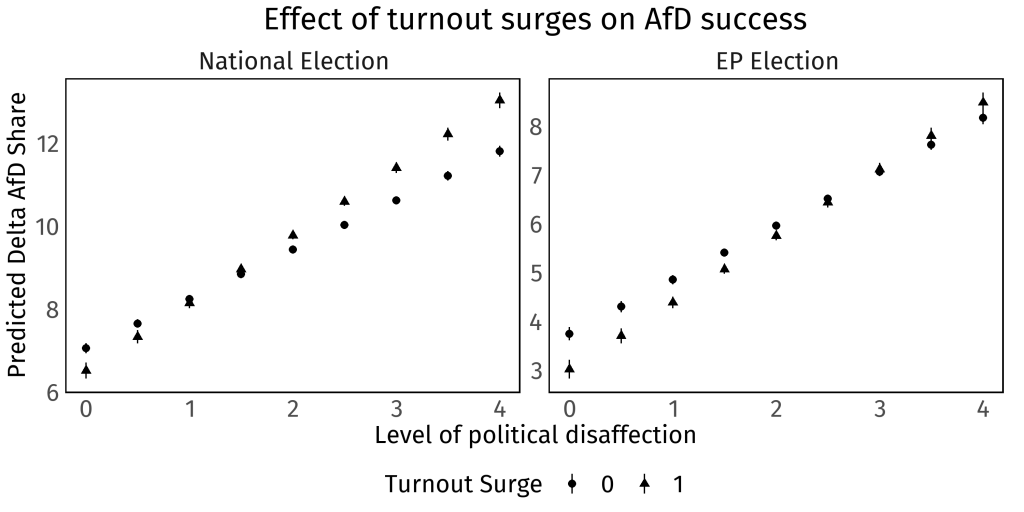

In a recent article for the journal Party Politics, Arndt Leininger and I show that the populist radical right can benefit from increased electoral participation, but only if voters harbour deep-seated feelings of political distrust and alienation in the first place.

When citizens do not harbour such populist sentiments or political grievances, our research shows that surges in turnout have the opposite effect, decreasing the prospects of the populist radical right. In such contexts, increased electoral participation appears to amplify the representation of plural and diverse policy preferences.

We draw on a new dataset that assembles the electoral results of the German populist radical right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) across more than 10,000 municipalities and city districts in six nationwide elections in Germany.

Focusing on the German case helps us measure levels of political disaffection from the period before a relevant populist radical right party existed. This is important, because prior research has documented that populist right parties not only benefit from voters’ discontent, they also accentuate it, particularly in opposition. Building on the literature of political distrust and its implications for electoral behaviour, we measure pre-existing political disaffection using an index that considers the rates of abstention and invalid voting in a local community, relative to the regional average.

the populist radical right can benefit from increased electoral participation, but only if voters harbour deep-seated feelings of political distrust in the first place

Our empirical analysis also pays attention to the fact that the AfD has many regional strongholds in which the local chapter might be more effective in campaigning and mobilising voters on the ground.

By linking the party’s election results to data on the geographical scope of these local party branches, we measure only such surges in turnout not sparked by the mobilisation efforts of the AfD. Thus, a ‘turnout surge’ is understood as an increase of turnout in a municipality that substantively exceeds the average growth or decline of turnout among all municipalities exposed to the same local party chapter of the AfD. Our analysis then compares municipalities that saw such peak-level increases of turnout with municipalities located in the same region but without a ‘turnout surge’.

The results show that, on average, the populist right stands to benefit from greater electoral participation — a phenomenon that could be considered a ‘dilemma of inclusion’ from a liberal democratic perspective.

The effect is, however, also conditional upon voters’ level of prior political disaffection, as you can see in the graph. In line with scholarly accounts of political grievances and social disintegration, turnout surges amplify the electoral prospects of the AfD only when voters harbour strong feelings of political disaffection that pre-date the existence of the party.

the populist right stands to benefit from greater electoral participation — a phenomenon that could be considered a ‘dilemma of inclusion’ from a liberal democratic perspective

The recent rise in electoral participation levels across some Western European countries may thus fuel the success of the radical right under conditions of high political disaffection.

Our results demonstrate that increased popular participation acts to impede the success of the populist right whenever turnout surges do not reflect the mobilisation of 'anti-system citizens'.

In local communities with low baseline levels of political disaffection, surges in turnout appear to increase the representation of plural policy preferences. This effect is particularly pronounced during European Parliament (EP) elections, which are marked by low electoral salience and widespread electoral abstention — even among voters who are otherwise not politically alienated.

In short, local communities without a history of political disaffection may still be able to mitigate the rise of the radical right through greater electoral participation.

Read the full article by Julia Schulte-Cloos & Arndt Leininger (open access) in Sage journal Party Politics