Writing to our political leaders is a core part of our democratic rights and traditions, but we know almost nothing about the contents of a leader’s mailbag. Daniel Casey opens the mailbag for one Australian Prime Minister to discover a very different measure of public opinion

Have you ever been frustrated enough about politics to write to your Prime Minister or President? Every year, the Australian Prime Minister receives around 150,000 letters. However, up to now, we haven’t known anything about these letters.

While others have undertaken qualitative analysis of letters to leaders, little is known quantitatively. My newly released paper, published by the John Howard Prime Ministerial Library, uses these letters to provide a new avenue to explore public opinion in the first five years of the government of Australian Prime Minister John Howard (1996–2000). The language in the letters also reveals how citizens sought to engage with their political leaders; people felt they had a fundamental right to engage directly with their leader.

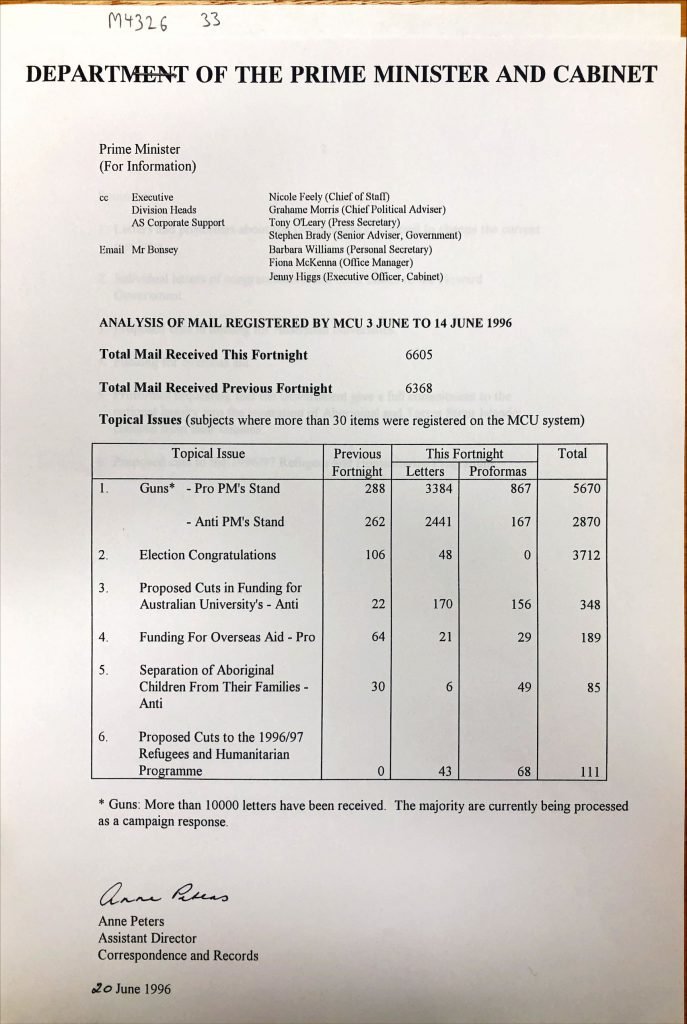

Each fortnight, Prime Minister Howard received a brief with the amount of mail received. The brief also included a list of topics about which he had received at least 30 items of correspondence. Using these newly released fortnightly briefs, I have built a dataset of the volume and topic of letters. Correspondents' issues ranged widely, from animal rights to land clearing, to dual citizenship.

Democracy requires linkages between the public and their representatives. This necessitates both that the public speak and that leaders listen. While media usually focus on opinion polls, politicians listen to the public in many different ways.

For individuals, letters are a relatively easy way to express their opinion. If someone has decided to devote time and resources to contact a politician, it demonstrates a level of intensity of feeling. It also shows that they are actively interested in political issues – a member of the ‘attentive public’. Using these letters, therefore, helps us to appreciate the different voices reaching political leaders.

My research shows that the topics of the letters differ significantly from other measures of public opinion. I coded these letters against the international Comparative Agendas Project codebook. Surprisingly, the top three topics were international affairs and foreign aid, transportation, and labour and employment. Such topics are not usually high on the public agenda.

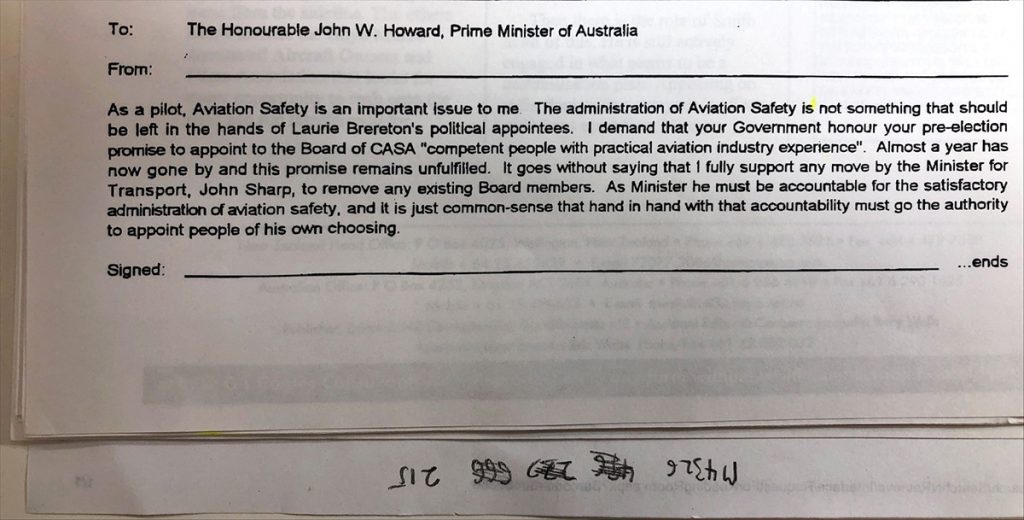

Each of these top three had one or two specific reasons behind them. The Indonesian attacks in East Timor and Australian-led United Nations military intervention (INTERFET) prompted the letters on international affairs. Similarly, the transportation topic was driven by a pro forma letter-writing campaign about Sydney’s proposed second airport. The labour and employment topic, meanwhile, was given impetus by another pro forma letter-writing campaign about childcare funding. This also created a highly ‘punctuated’ pattern.

The topics of letters differ significantly from other measures of public opinion, and are often reflective of specific concerns among interested groups

These results differ significantly from conventional measures of public opinion and the public agenda. Throughout my period of study, opinion polls consistently found that the most important problem(s) facing Australia were the economy, health, education and social welfare. However, in Mr Howard’s mailbag, these ranked 7th, 6th and 12th respectively. The two that claimed the top spot in his mailbag, international affairs and transportation, ranked only 12th and 11th respectively in opinion polls.

That letters are not representative of mass opinion does not mean they can be ignored. They represent an intensity of opinion by a politically active subgroup of society. Like letters to the editor, they are a ‘hazy reflection’ of opinion. They also reflect only one side of the issue – opposing the government’s position or calling for the government to act. While the letters don’t reflect the balance of public opinion, they can show the breadth and intensity of the opposition or the level of organisation of oppositional interest groups, and help identify issues that are ‘under the radar’.

Mr Howard also paid significant attention to the balance between letters and pro-formas. Most topics were driven almost entirely by pro-forma letter-writing campaigns by interest groups.

The significant difference between mass opinion and the topics of the letters mean that more attention needs to be paid to these letters in order to paint a fuller picture of the relationship between public opinion and public policy.

As well as expressing policy opinions, there are many deeply intimate and personal letters, a ‘last ditch’ pitch for assistance. The personal letters show that citizens expect a personal relationship with their leaders. People disclose details of their childhood sexual abuse, or the ‘horror of watching my daughter’s trauma as she slowly, despairingly, distressfully [died]’. Whoever read these letters, whether Prime Minister or junior public servant, must have recognised the connection the writers sought with their leader and the trust being placed in that relationship.

Letter writing has been part of democratic tradition for hundreds of years. These letters provide an alternative ‘bottom-up’ history, and a nuanced lens on the opinion of the ‘attentive’ public. Datasets like this allow for a range of new research opportunities in public opinion, punctuated equilibrium, policy processes, responsiveness, political participation and interest groups.

These letters provide an alternative ‘bottom-up’ history, and a nuanced lens on the opinion of the ‘attentive’ public

While Mr Howard appreciated the importance of his mailbag, he knew that the letters to him were driven by interest groups, and often on topics that would be unlikely to swing votes. Nevertheless, the trends were an early warning of changes in public opinion, and the intensity of those opinions. Equally important, however, was the individual letter. One well-written, heartfelt letter could be more powerful than thousands of form letters. As Mr Howard said: ‘[Y]ou need anecdotes, you need stories… and I think we, all of us, as political leaders need to remind ourselves that you have to provide real live flesh and blood examples.’