Substate laws and policies may play a key role in promoting or hindering the socioeconomic participation of those who face intersectional discrimination. Alexandra Tomaselli examines how women and LGBTQIA+ individuals cope with their access to work, education, and services in South Tyrol and Catalonia

For women and LGBTQIA+ people in South Tyrol (Italy) and Catalonia (Spain), gender and ethnicity and/or race intersects in their daily life. In many cases, this intersection operates with other social drivers (e.g., age, disability, agency, level of education) and external factors (e.g., sexism, heteronormativity, gender-based violence). Yet these are often ignored by statistics and thus by local laws and policy.

This gap becomes particularly evident in the socioeconomic sector; that is, in access to employment, education, and public services. The empirical and explorative applied research project, InGEPaST, therefore tries to identify how such drivers and factors correlate. The project also considers how substate laws and policies in this sector could be reformed.

For women and LGBTQIA+ people, access to the workplace is affected by social drivers such as age and education level, but also by external factors such as sexism and gender-based violence

South Tyrol and Catalonia are two bordering substate units with robust self-governments in two Mediterranean states with strong patriarchal cultures. They are home to both linguistic-historical minorities and a growing population with a migratory background. In both cases, the percentage of the latter is higher than the national average. This is due in part to their wealthy economies, which are primarily based on agriculture, tourism, and other services. Indeed, both South Tyrol and Catalonia register impressively low unemployment rates, including for women. At the same time, they each accommodate, in divergent ways, three linguistic groups. Italians, German-speaking and Ladins in South Tyrol; Spaniards, Catalans and Aranès in Catalonia. Both substate units also are home to historical and recent communities of Roma and Sinti.

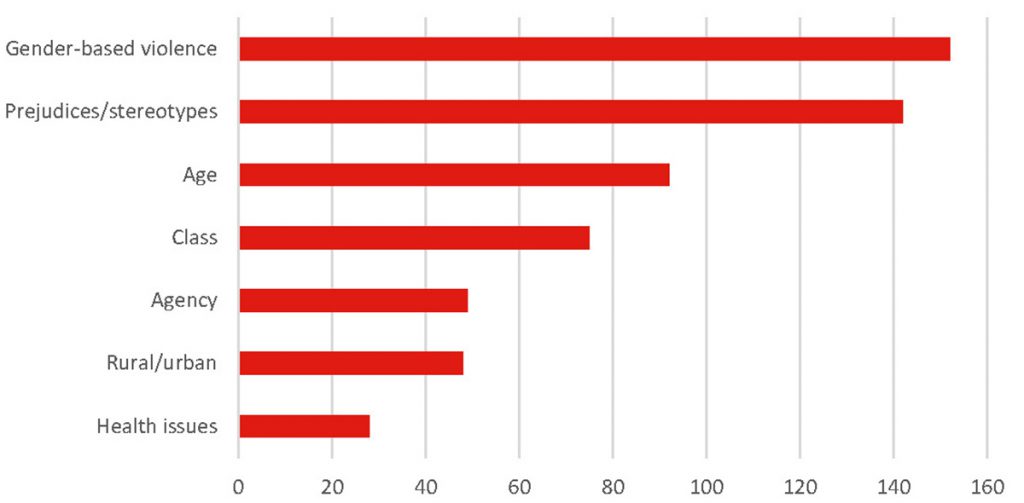

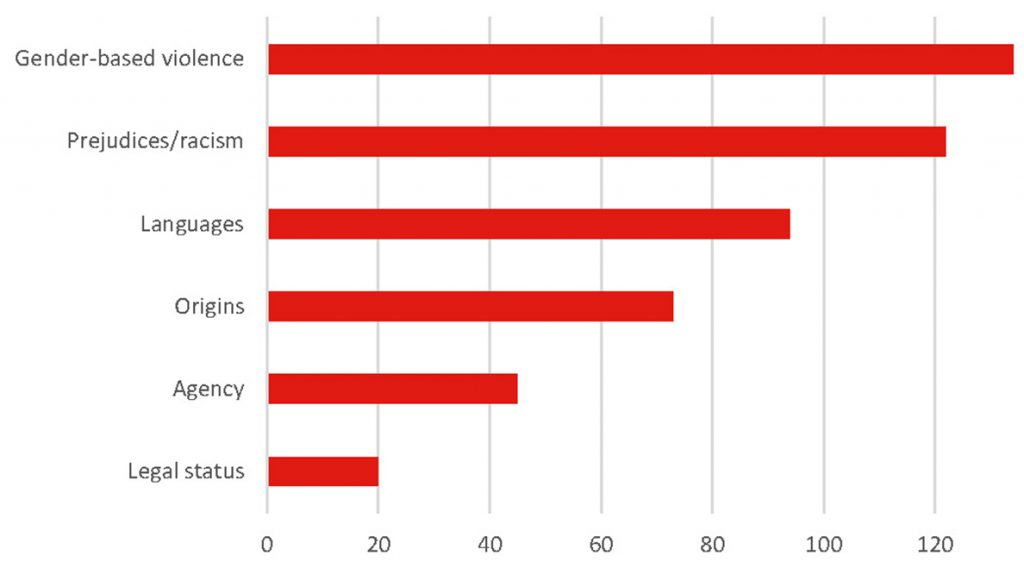

During the first part of the project, I interviewed 43 civil society organisations. These organisations deal with women’s and LGBTQIA+ individuals’ rights, awareness raising, assistance, and advocacy in both substate units. The interviews unveiled which social drivers and external factors hinder the socioeconomic participation of local women and LGBTQIA+ individuals (those who have citizenship) and women and LGBTQIA+ individuals with a migratory background.

Gender-based violence, along with prejudice and stereotyping, are the factors with the greatest hindering effect on access to work, education, and services. Victims of gender-based violence, for instance, must usually change their address, and often their job, for security reasons. Indeed, women may find themselves at the intersection of gender and ethnicity and/or race as well as that of gender-based violence. Moreover, they often carry the extra burden of childcare. All this combines to further hinder women's access to the job market. It also prevents access to training and essential services, such as housing.

Incidents of racism, language discrimination, along with prejudicial actions based on class, agency, and origins, are also significant. The ability to speak a substate unit’s language is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it is a key requirement, especially to work in the service sector. On the other hand, employers prefer workers who cannot speak the language, because they are unlikely to claim their rights. Moreover, women and LGBTQIA+ individuals with a migratory background tend be classified in accordance with their geographical origins. This often results in discriminatory division into types of jobs (and, thus, salaries) in accordance with skin colour.

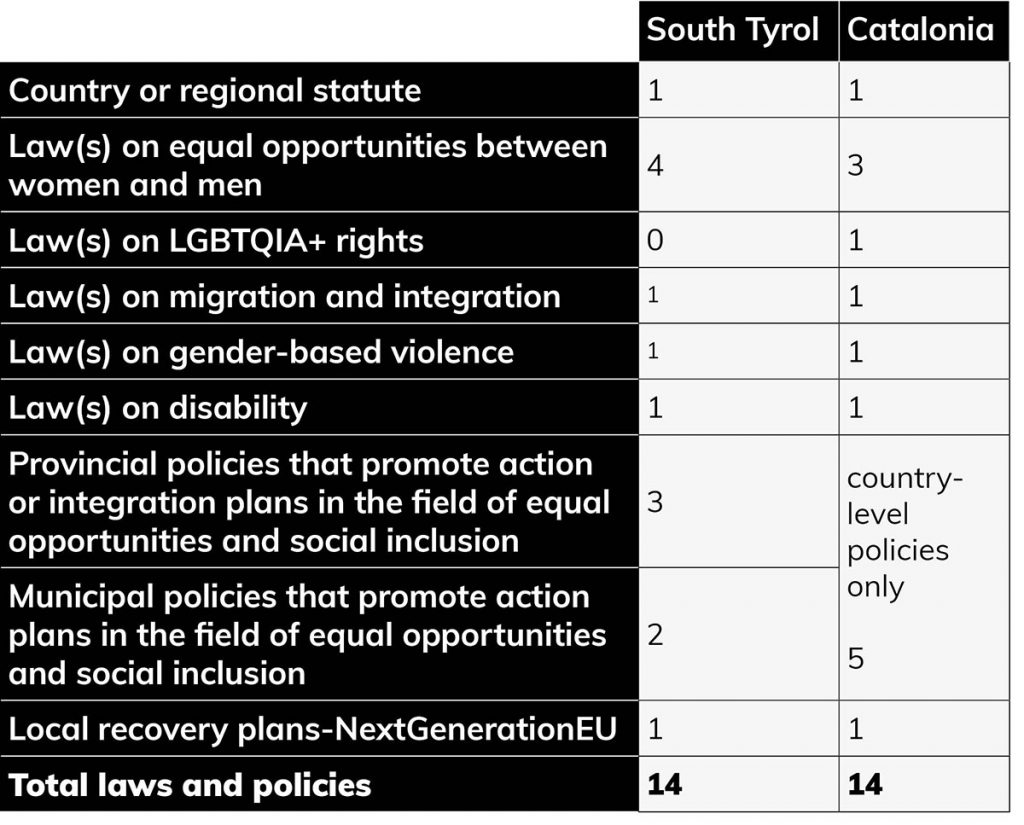

In the second part of the project, I examined the South Tyrolean and Catalan laws, policies, and action plans currently in force:

I also interviewed ten policy experts: seven in South Tyrol and three in Catalonia. These experts work in public administration bodies that oversee the protection and promotion of gender and cultural diversity, equal opportunities, antidiscrimination, and social inclusion.

Thematic analysis of the policy experts’ interviews points to several problems. First, the lack of autonomy in decision-making and of clarity in the competences of local bodies may hinder their actions even when they are framed by ad hoc laws and policies. The private sector tends to apply ineffectively the prescriptions of local laws on gender equality and, for example, disability. This means they are unable to pursue the proposed actions. The public sector suffers from a lack of more incisive obligations in the field of gender and diversity.

The private sector tends to apply local laws ineffectively; the public sector suffers from a lack of obligations in the field of diversity

Overall, policy experts also suggest adopting a more effective sanction system, albeit not necessarily based on economic penalties. Ensuring gender equality requires mediation. Hence, a mechanism that effectively informs about the complexities of gender, ethnicity, and race – as well as other social drivers and external factors – is desirable. This mechanism becomes particularly urgent in the current age of polarisation vis-à-vis gender and migration.

My content analysis of South Tyrolean and Catalan laws, policies, and action plans aimed to identify the key drivers and factors hindering access to the workplace. The results show that the factors the interviewed women and LGBTQIA+ civil society organisations identified as the greatest barriers to work are, essentially, ignored by policy.

While both South Tyrol and Catalonia have adopted an ad hoc law against gender-based violence, this legislation is rarely considered in the labour sector

Both regions have adopted an ad hoc law against gender-based violence. The other instruments, however, rarely consider this factor when applying other measures. A partial exception is the action plan of the pioneering South Tyrol municipality of Meran – the first in Italy to pursue such an initiative. However, the plan opted for a strong binarism, and failed to address the intersection of gender and disability.

In sum, both substate units have adopted laws, polices, and action plans that deal with specific sectors. However, they tend to ignore not only how gender and ethnicity and/or race intersect but also how several other drivers and factors hinder their application.