Eva Anduiza and Guillem Rico argue that the rise of the Spanish radical populist right is partly the result of sexist attitudinal backlash. The electoral consequences of changes in sexist attitudes seem to be related more to heightened feminist mobilisation than to the increasing visibility and normalisation of the radical right

We generally understand backlash as a conservative reaction to progressive advances in society. The term is frequently used to explain the rise of the populist radical right. However, it functions mostly as a narrative tool rather than a theoretical model subject to empirical testing.

The backlash narrative has attracted criticism for several reasons. Firstly, it oversimplifies the situation. It assumes, for example, that there has been progress when often the rise of the radical right does not require a well-identified progressive trigger. Secondly, it hinders our ability to examine the problematic questions and differences that arise on the progressive side of politics. Using the backlash narrative, we risk adopting the same Manichean perspective that has been so fiercely criticised in analysing populism. In this view, politics is a dialectic between two poles, one progressive (hence always good), and another reactionary (always bad).

We suggest using the concept of backlash to explore the interplay between political events, attitudinal change, and vote choice

Despite these well-founded arguments, we think that the concept of backlash may still be useful. Until now, researchers have used backlash as a general explanation for systemic reactions with a deterministic bipolar perspective. However, scholars can also use the concept to explore the dynamic interplay between political events, attitudinal change, and the electoral consequences of these phenomena over time.

Progressive advances that challenge traditional customs and dominant values take time to occur. However, gradual change may occasionally be marked by individual episodes that appear to signal critical junctures in the process. Such signature events highlighting social change present unique opportunities for exploring the dynamics of reaction.

We may look, for example, at how sexist attitudes shift after a major feminist mobilisation, and how this affects vote choice. To measure this shift, we require individual-level data that analyses attitudes prior to, and following, the mobilisation.

On 8 March 2018, Spain witnessed an unprecedented wave of feminist mobilisation. Women took to the streets in every large city, including more than 100,000 in both Madrid and Barcelona. A year later, the radical-right party Vox entered the Spanish parliament with a sizable number of seats.

A year after Spain's unprecedented wave of feminist mobilisation, the radical-right party Vox secured a significant number of seats in the Spanish parliament

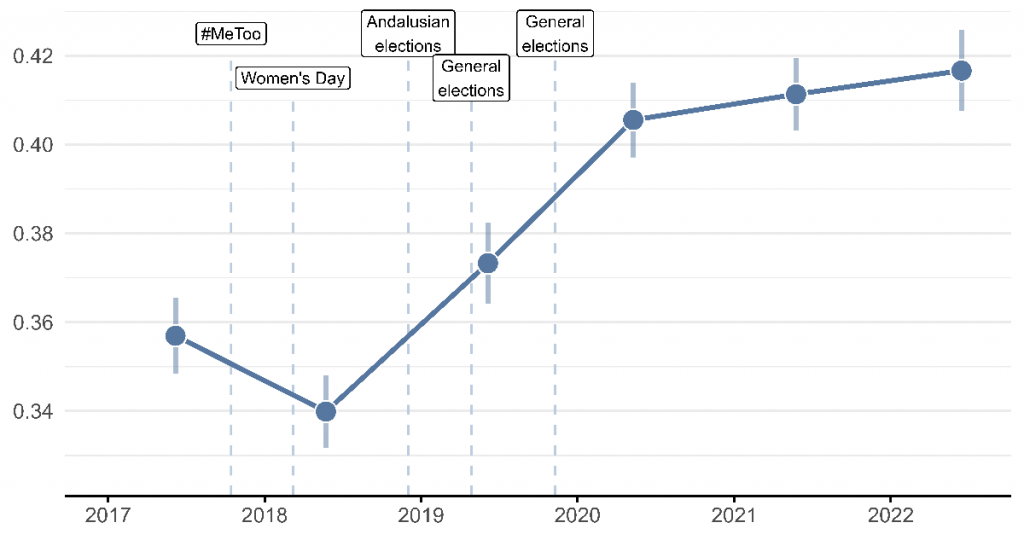

The graph below shows levels of modern sexism, on a scale from 0 to 1, between 2017 and 2020. It also shows key political events during each time period, including feminist demonstrations and elections, which allows us to measure how sexism levels change afterwards. Average levels of sexism decrease following the feminist mobilisations of 2018. However, they then increase after the 2019 entrance of the radical right into parliament.

The changes are not huge, but they are significant. Interestingly, they are greater than in other countries such as the US, where sexist attitudes remain reasonably stable over time.

But averages mask a significant amount of variation in these changes over time. Not all citizens' attitudes change, as the average pattern shows. Despite the fact that average levels of sexism decreased after the feminist mobilisations, some people's sexist attitudes remained stable – or even grew higher.

We call this backlash attitudinal change, because it seems to be a reaction to feminist mobilisation before any radical-right party has appeared on the landscape. What's more, it goes against the general trend of decreasing sexism. This attitudinal change relates to changes in subsequent voting patterns for the radical-right party Vox in the April 2019 elections.

After Vox entered parliament, average levels of sexism went up. We consider individual increases in sexism at this time as the normalisation of attitudinal change, because it happened during a period of rising visibility for the radical right, and followed the general trend of increasing sexism.

People who become more sexist after a feminist tide appear to be more likely to vote for a radical-right party later on

This normalisation of attitudinal change, however, did not appear to significantly affect the likelihood of voting for Vox – at least not until the time of our study. The reason for this might be that, in this instance, increases in sexism spread across the entire population, as one would expect from a process of normalisation.

Causality between the macro event and these attitudinal and behavioural changes is still challenging to prove, and requires further scrutiny. However, our evidence points clearly towards some pattern of gender backlash that makes people who become more sexist after a feminist tide more likely to vote for a radical-right party later on.

Our evidence suggests that sexism is indeed a relevant predictor of radical-right voting. Scholars should thus routinely consider sexism in their explanations of vote choice, despite the fact that its importance is not constant over time. Sexist attitudes – and their electoral consequences – seem to be sensitive to contextual events.

Increases in sexism are, of course, cause for concern. Yet not all increases become electorally consequential to the same degree. The results of our research highlight some paradoxes and difficulties in the struggle to extend egalitarian values.

Very interesting.

However,it seems like you are suggesting that the events caused sexist attitudes to change without being explicit about it.

If you think so, just claim so. And if you claim so, back it with the right evidence: just showing a change after an event is not sufficient for establishing causation.

That said, the peace is very interesting.