Bhimrao Ambedkar was many things, and is often known as a political activist and an anti-caste thinker. In addition, Scott R. Stroud positions Ambedkar as a theorist of democracy who extends the pragmatist tradition

Democracy, as this series makes clear, seems to impose on its practitioners an impossible demand. They must push vigorously for their vision of the world and their community, at times against other community members who think differently. But at the same time, they must remain open to other members of the political community. Democracy demands that we assert ourselves in improving our communities while remaining open to disagreement about how that community ought to be improved.

This paradox clearly applies to elected leaders making policies. However, limiting the challenges of democracy to formal decision-making procedures and officials is an artificial truncation of what is at stake in our communities.

To pluralists, democracy goes deeper than periodic votes or organised decision-making – instead, it is a way of life

The pluralistic tradition known as pragmatism is associated most prominently in American thinkers such as Charles Peirce, William James, John Dewey, and Jane Addams. They all sensed that democracy went deeper than periodic votes or organised decision-making. Its currents ran below dry books and abstract theories about political ideals. It centred on how we saw the other individuals we lived with and, perhaps, could form a sort of close community in our everyday lives. Pragmatism saw democracy as a habit or way of life.

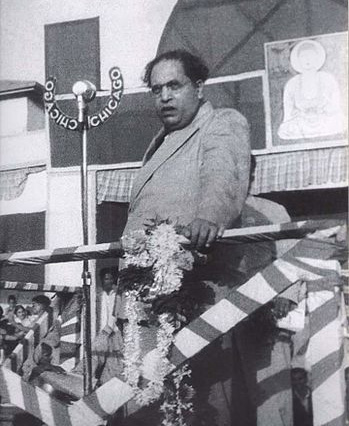

If there’s a story of pragmatism in India, it must centre on Bhimrao Ambedkar (1891–1956).

Ambedkar took courses from Dewey and others while studying at Columbia University in 1913–1916. As an ‘untouchable,’ Ambedkar felt the sting of millennia of caste traditions and customs. For many around him, his physical presence and touch was religiously impure.

Even after he earned five different graduate degrees from institutions in America and Britain, he could not find housing because of his caste status. Caste ostracisation affected him in both social and economic spheres. In the light of these experiences, he committed to resisting and reforming the structures that promote caste oppression in India.

Ambedkar held a lifelong interest in his teacher Dewey’s thought, collecting his books into the final years of his life. Dewey's themes proved valuable in the battle against caste oppression. As a result, we can also speak of Ambedkar as a pragmatist philosopher.

Thinking about Ambedkar’s work as a new variety of pragmatism attunes us to his status as a theorist of democracy. He is well known as an anti-caste philosopher because he diagnosed caste divisions in Indian society as opposed to the sort of democracy he, and Dewey, desired. In doing so, he creatively added to the pragmatist idea of democracy as a way of life among citizens who often disagree with each other. By focusing on Ambedkar as a theorist of democracy and its unique iterations, we discover a compelling voice for our times of division and polarisation.

Ambedkar, as a theorist of democracy, adds something powerfully new to Dewey's ideas. He is a compelling voice in our times of division and polarisation

Ambedkar’s account shares Dewey’s quest for communities animated by shared interests. What he adds is powerfully new. Whereas Dewey tentatively postulated ‘growth’ as the ethical ideal moral activity, Ambedkar advanced the values of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

These values serve as semi-transcendent ideals that reside between timeless and absolute standards like divine commands, and more immanent views like Dewey’s that tend to picture morality as emerging from one’s group customs and history. The latter option would not work. The target of Ambedkar’s critique, after all, was the bulk of the Hindu tradition. This defined him as an ‘untouchable’ through its sacred texts and law books. The former also would not suffice. A pragmatist, Ambedkar was sceptical of any claims to access a moral standard residing outside the realm of experience and inquiry.

Ambedkar used liberty, equality, and fraternity in his theories because they represent separate, and sometimes conflicting, aspects of democratic experience

Ambedkar did not find equality, liberty, and fraternity to be useful because they had some special origin. Instead, they were useful because they attach to separate, and sometimes conflicting, aspects of democratic experience. We each want to set our life’s course the way we desire, hence we value freedom or liberty. We react negatively to claims that some are naturally better or superior to others, especially if we are on the lower end of that claim of inequality. Hence, we value equality.

Oppression becomes visible when equality is rejected or liberty negated for those we believe should matter. Therefore, fraternity, or fellow-feeling, is also vital for pragmatists like Ambedkar. It points to what we want to accomplish in acting on our theories of democracy. We seek communities animated by shared interests, and attitudes among members that see others as community members, not merely as obstacles or enemies to overcome.

Approaching Ambedkar as a theorist of democracy offers an interesting and novel pragmatist account of democracy as a way of life. It posits a complex notion of justice, one that recognises the lack of freedom and the presence of inequality, but that puts these problems in a productive tension with the demands of fraternity or fellow-feeling. Justice becomes the creation of a state that balances a maximum of social equality, liberty, and fraternity.

We cannot sacrifice one value for others in our political activity. How can we address inequality while preserving as much freedom as possible? How can an activist or political leader free those who are oppressed while still maintaining the conditions for fraternity with allies – and those who might be seen as enemies?

Democracy means forming community among those who agree and those who disagree. Ambedkar recognised this, and thus is a vital thinker to our discussions of democracy in a time of deep divisions.

No.97 in a Loop thread on the science of democracy. Look out for the 🦋 to read more in our series