Women have made great strides towards equal representation in parliaments across the world. Their short parliamentary careers, however, still stop them from representing their constituents as effectively as men colleagues, write Ragnhild Louise Muriaas and Torill Stavenes, in the first of their four-part blog series to mark International Women’s Day on Friday 8 March

The overarching topic of this year’s International Women’s Day is Invest in Women: Accelerate Progress. Over the last decade, we have witnessed myriad innovative initiatives to use policies, funding and training to secure a higher presence of women in legislative politics. Political inequality, however, is still very much with us.

In this week's series, we give some emerging and leading scholars in gender and politics the opportunity to address the question: what do we know about women's power and influence in contemporary politics?

Our first instalment outlines how women and men have failed to achieve equal status in contemporary parliaments. Women MPs still struggle to take their rightful place when decisions are made, and their parliamentary careers end sooner than men’s.

There has been remarkable ingenuity in efforts to bring women into politics. To shrink the gender gap in elected office, well-crafted campaigns and policies concerning political financing have succeeded in developing a fairer political environment for women.

Well-crafted campaigns and policies concerning political financing have succeeded in developing a fairer political environment for women

In France and Ireland, parties are fined if they fail to comply with an established gender balance norm. In countries including the US, Malawi and Japan, women candidates receive training and extra funding to build their electoral muscle.

Research also finds that gendered political financing is successful only if the conditions are right. But is all this creativity in getting women into politics enough to overturn their subordinate political status?

Our concern is that while women can get into politics, they don’t stay.

Parliamentarians capitalise on their career length every day. Longer tenure in a parliamentary assembly brings easier access to high office, exclusive networks, and knowledge. Simply put, tenure is power. But when men systematically have longer parliamentary careers, this disadvantages women as representatives – for their parties and for their constituents.

Longer tenure in a parliamentary assembly brings easier access to positions, networks, and knowledge. Simply put, tenure is power

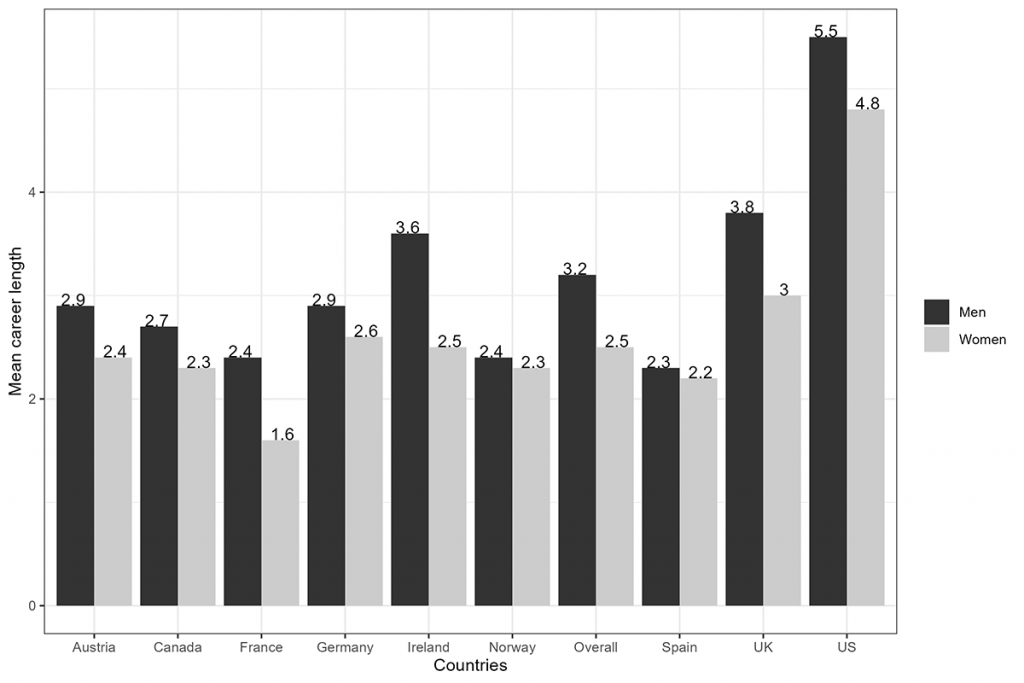

Our research documents that men have, on average, longer legislative careers than women. Research shows that between 1965 and the present day, men politicians outlast women in Ireland, the UK, Canada, the US, Spain, France, Germany, Norway, and Austria. In these countries, women have a career length averaging 2.5 terms, while men average 3.2 terms.

It’s true that the situation is improving. Differences in career length are smaller in parliaments with better gender balance. In Norway, where since 1989 women have, on average, comprised 40% of representatives, gender differences in career length have almost been wiped out. The same is true in Spain, where 44% of current parliamentarians are women. France, Ireland, and the UK lie at the opposite end of the spectrum.

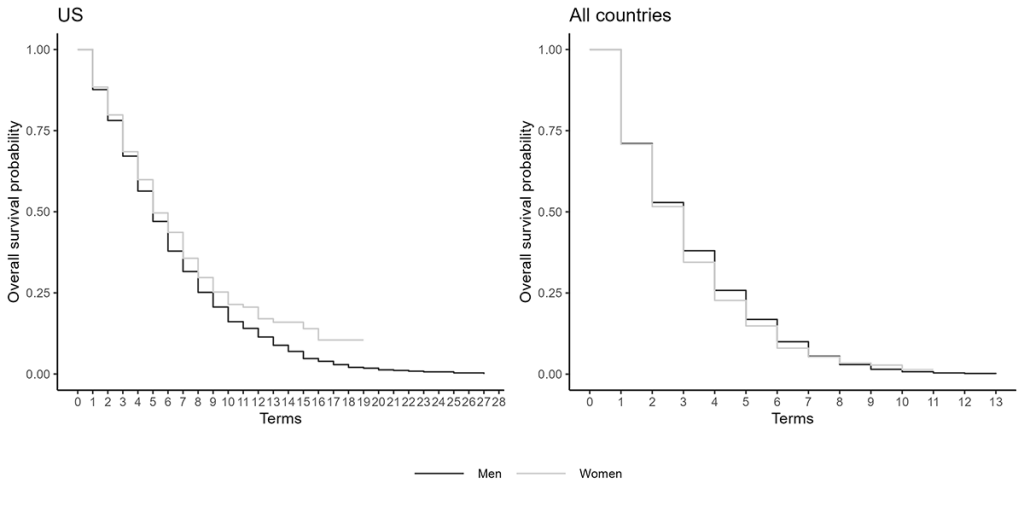

How can we channel the creativity used to bring women into the political fold into innovative strategies to retain them? Our research shows that we need to take decisive action. Men, on average, are more likely to survive in office longer, and more likely to endure in parliament after two terms. Interestingly, the gender difference is particularly visible from three terms onwards. More women than men – either voluntary or involuntarily – struggle to make their careers last.

In the US, the picture is slightly reversed. In fact, women in the House are more likely than men to survive 19 terms, even if US politics generally struggles to achieve gender balance. Despite continued under-representation, the few women who have been elected since 1965 have been remarkably tenacious at retaining their seats.

In the US, the few women who have been elected since 1965 have been remarkably tenacious at retaining their seats

Taken together, and as mentioned in our previous blog for The Loop, our research shows that to understand wide gender gaps among senior politicians, we must look at career length and gender balance simultaneously.

Women's shorter tenure in office affects their chances of equal respect in politics. In her theory of social justice, Nancy Fraser put forward a compelling argument about how representation is linked to recognition and redistribution.

Fraser argues that achieving gender balance in representation through rules alone will not ensure equality. Economic disparities and cultural norms can still lead to unequal dynamics in decision-making bodies, subordinating certain groups unfairly.

Gendered differences in both career length and seniority exacerbate this inequality. This suggests that measures to motivate, recruit and retain women candidates are of the utmost importance for making contemporary parliaments not just gender balanced in numerical terms, but also substantively.

Subsequent contributions to this ♀️ International Women's Day series will broaden our understanding of women’s power and influence in contemporary politics: