The Biden administration and 118th Congress failed to adequately reform and modernise the organisation of US diplomatic posts. Michael Walsh argues that Trump should urgently reassess the US Foreign Affairs Manual's conceptual model for organising such positions

If the Trump administration continues the current model of diplomatic post organisation, the US Department of State will continue to struggle to align the operations of such posts with contemporary political realities and the external environment.

Within its first 100 days, Trump and the 119th Congress should therefore work to overhaul the conceptual model for post organisation declared in the Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM). Among other things, both branches should demand that the bureaucracy produce a revised conceptual model that is more accurate, consistent, complete, current, efficient, effective, and understandable.

The FAM declares the 'structures, policies, and procedures' that are to 'govern the operations' of the Foreign Service, United States Department of State and, when applicable, other federal agencies', including the organisation of US diplomatic posts.

Specifically, 2 FAM 100 declares the structures, policies, and procedures related to the organisation of US diplomatic posts. Among other things, that chapter defines the key concepts and their relations.

The problem is that many existing key concepts and their relationships remain undefined. The following examples help illustrate that point.

One problem with the current version of 2 FAM 100 is that it fails to account for a number of key concepts already operationalised in diplomatic practice.

A good example is the virtual embassy. Over the last couple of decades, the US Department of State has created virtual embassies for a number of independent states around the world. One of the most famous is its Virtual Embassy for Iran. When it was 'opened', it made international headlines.

However, 2 FAM 111.2 does not define what counts as a virtual embassy. Nor, more than a decade later, does it clarify its relationships with other key concepts.

There is another problem with the current version of 2 FAM 100. It does not account for US diplomatic posts that are temporarily or semi-permanently embedded within other embassies.

A good example is an embassy operating out of another embassy following a suspension of operations. Prominent recent examples include the US embassies in Libya, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen.

When such suspensions of operations occur, this often creates a new component within the other embassy. This component is sometimes described as an office, as in the case of the Office of Sudan Affairs at the US Embassy in Ethiopia. Other times, it is described as a unit, as in the case of the Yemen Affairs Unit at the US Consulate General in Jeddah.

These types of posts are relatively common across the Middle East and North Africa. There is no definition, however, for what counts as an embedded post in 2 FAM 111.2.

A special case of the embedded post occurs in the case of an unrecognised entity.

A good example is the Palestinian Territories. At present, the US government does not recognise the Palestinian Territories as a dependency, independent state, or area of special sovereignty. It exists outside the US taxonomy for recognised entities. Nevertheless, the US Department of State has created an Office of Palestinian Affairs, embedded within the US Embassy in Jerusalem.

Problematically, 2 FAM 111.2 not only fails to provide a definition for this kind of diplomatic post. It also fails to mark a clear distinction between it and the diplomatic post in which it is embedded.

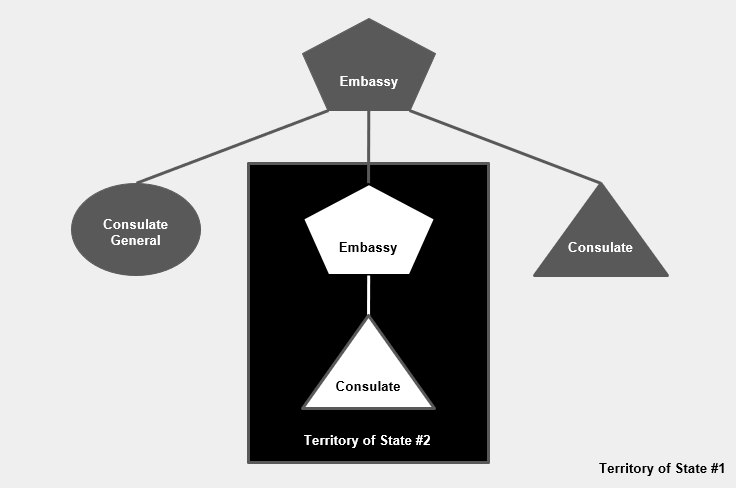

There is yet another problem with 2 FAM 100. It defines principal posts as 'those at the highest organization level within a particular country'. Subordinate posts it defines as 'posts of lesser organizational significance than the principal post'.

The problem is that this approach only makes sense if the structural relationships between US diplomatic posts fall within the limits of the sovereign territory of a single independent state. In reality, that does not always happen.

Take missions that have concurrent accreditation where there are posts that are the highest organisation level within a particular country that are effectively subordinate to a post that is the highest organisation level within another country.

A good example is the US Embassy in Vanuatu. Although designated as an embassy, it effectively operates as a subordinate embassy of the US Embassy in Papua New Guinea.

The problem is that 2 FAM 100 fails to account for these sorts of post complexes. Nor does it account for more than one level of primary-subordinate relations, even though such relations already exist in low-priority locations such as Tonga and Vanuatu.

The Trump administration and 119th Congress should address the conceptual gaps in the organisational structure of US diplomatic posts. They should also anticipate that innovations in the organisational structure of US diplomatic posts will risk new conceptual gaps forming.

To future-proof 2 FAM 100, Trump should therefore incorporate explicit provisions that take effect in the event of fundamental changes in the key concepts, corresponding structures, and operating environments of US diplomatic posts.

Among other things, that might include a statutory requirement that the US Secretary of State must deliver an annual certification to the Congressional committees of jurisdiction that no changes are required to the organisational structure of US diplomatic posts to achieve the US government's national security and foreign policy objectives.