Not all conspiracy theories that spread on social media remain popular over time. Courtney Blackington and Frances Cayton argue that conspiracy theories which map onto salient cleavages are more likely to persist and spread online. They find that elites who endorse such conspiracy theories do not always attract engagement unless an event occurs that makes those conspiracy theories salient

On social media, conspiracy theories can reach new audiences, attract new believers, and spread widely. However, not all gain traction. What influences how much engagement a conspiracy theory (CT) earns on social media?

Previous studies on conspiracy theory spread focused on belief in a specific CT at one moment in time. Yet, some conspiracy theories have centuries-old roots while others quickly lose popularity. Even short-lived CTs can be politically consequential. We therefore need to understand when and how conspiracy theories gain and maintain online engagement.

We analysed one year of tweets engaging with conspiracy theories about a plane crash in Poland. Our aim was to identify what features of these CTs enable some to become popular.

We assessed whether different framings affect how much engagement a conspiracy theory earns. We also explored whether politicians who spread such CTs get punished or rewarded for doing so.

In April 2010, 96 high-ranking Polish officials flew to commemorate a 1940 massacre, wherein the Russian People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs murdered over 21,000 Polish intelligentsia and military officers.

En route to these commemorations, the plane crashed. All people on board died, including then-President Lech Kaczyński. Many, but not all, of the politicians who died in the crash belonged to the populist Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS) party.

Official investigations revealed that thick fog, pilot error, and poor visibility during the plane’s descent caused the crash. However, conspiracy theories quickly emerged claiming that explosions were responsible.

These CTs often blame the crash on either the Platforma Obywatelska (PO) party, on the PO leader Donald Tusk, or PO in collusion with Russian officials. While PiS officials did not endorse these conspiracy theories immediately, they soon dominated its rhetoric.

These conspiracy theories allow us to test whether conspiratorial framings garner more social media engagement when they invoke domestic partisan threats or foreign threats. They also enable us to assess whether and when politicians earn more social media engagement when spreading them.

People gather each month in Poland to memorialise the Smoleńsk crash. Simultaneously, discussions about the crash arise on social media. To measure engagement with conspiracy theories, we analyse the regularity of this online discourse.

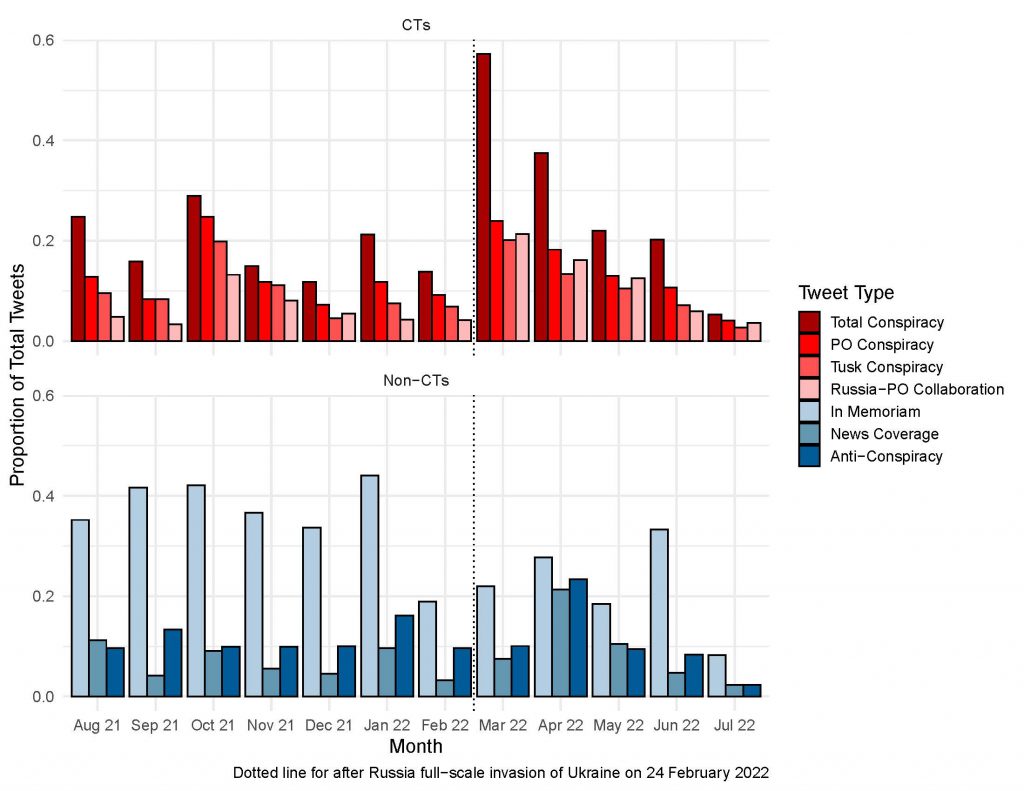

We scraped tweets from August 2021 to July 2022 on the day before, day of, and day after the monthly commemorations, using a list of hashtags related to the Smoleńsk crash. We then hand-coded each tweet for references to domestic political actors, foreign actors, conspiratorial discourse, and more.

Not all tweets about the crash invoke conspiracy theories. In any month, conspiratorial tweets composed between 5.25% and 57.23% of the sample, which allows us to compare conspiratorial and non-conspiratorial tweets.

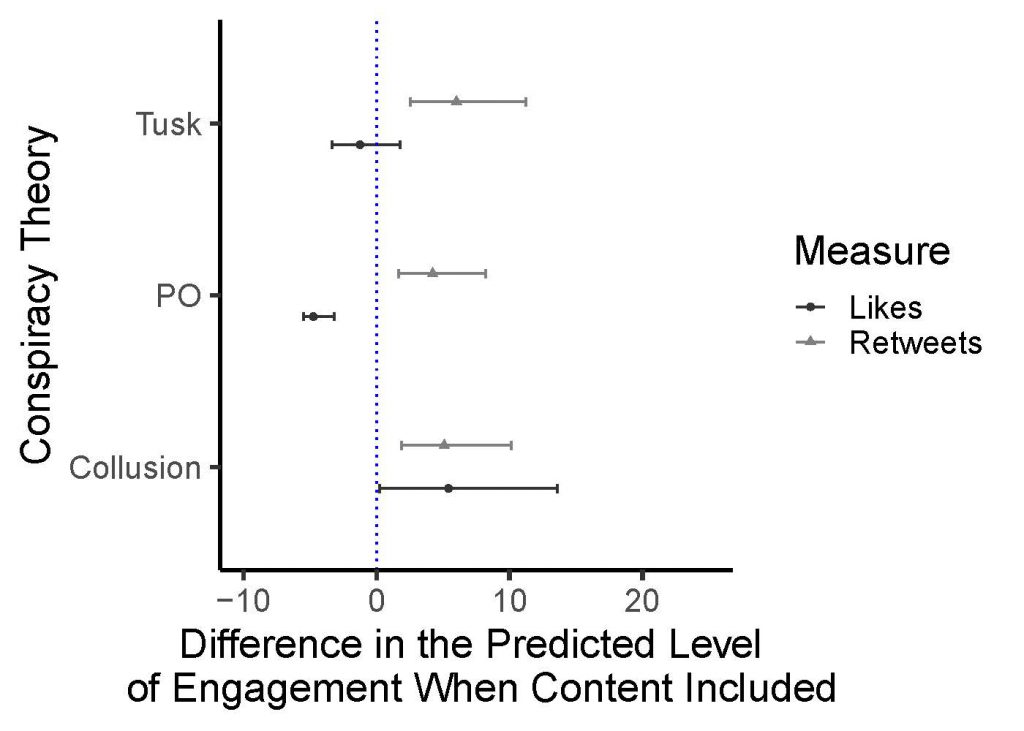

We found that tweets endorsing domestic partisan threat conspiracy theories are retweeted — but not liked — at higher rates. By retweeting, users bring greater attention to domestic partisan threat conspiracy theories, making these tweets go viral. However, users may not publicly endorse the tweet by liking it.

By contrast, when tweets invoke a foreign threat by claiming Russian and PO officials colluded, they are more likely to be retweeted and liked more than tweets about Smoleńsk, which lack these conspiracy theories.

When politicians spread conspiracy theories, they risk alienating moderate voters — even as such CTs can attract more extreme voters. Thus, we expected — and found — that in normal times, politicians would not get more social media engagement when endorsing conspiracy theories.

Does this change when an event occurs that can appeal to the central threat frames invoked in a conspiracy theory?

The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine began on 24 February 2022, about halfway through our scraping period. Russia is seeking regime change in a neighbouring country through violent means. We therefore expected the invasion would increase the plausibility of conspiratorial claims that Russia might have assassinated Polish leaders.

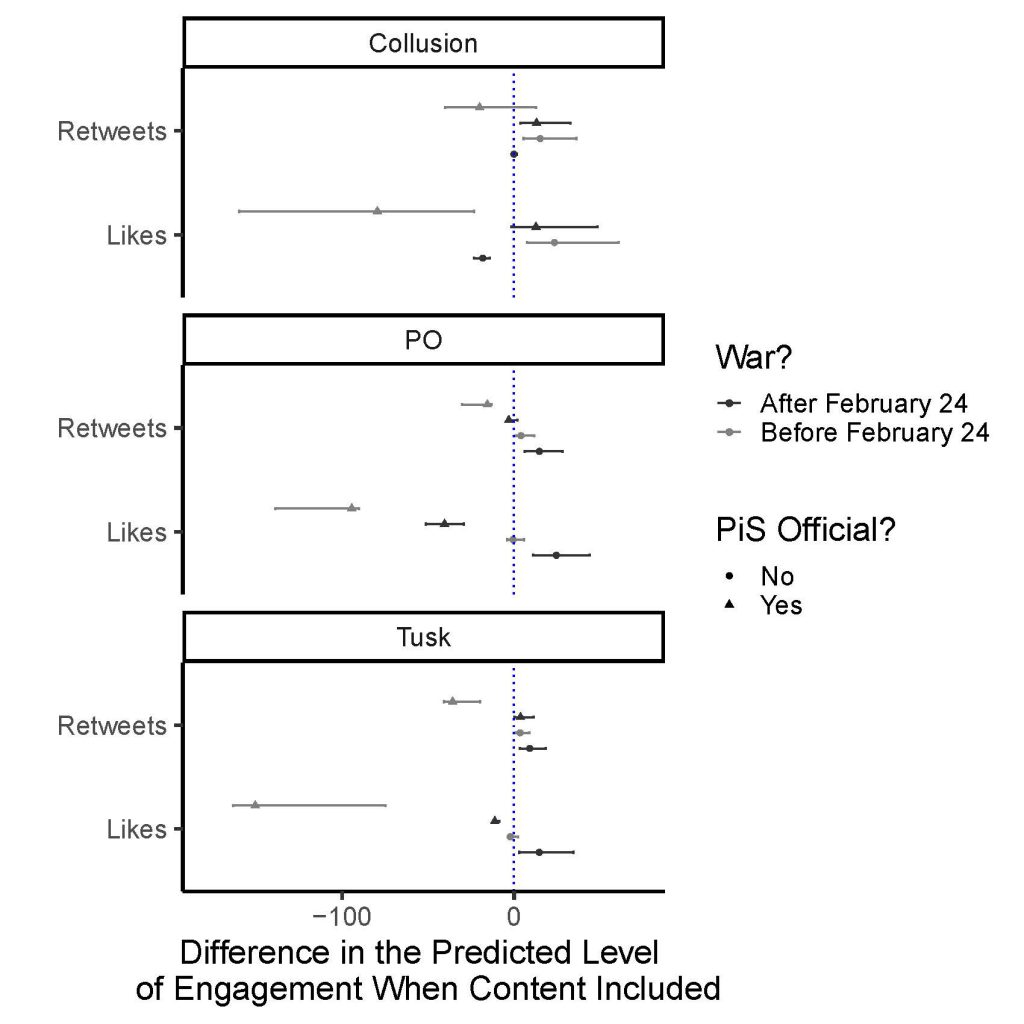

In turn, politicians who invoke these conspiracy theories after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine might get rewarded after the war, but not before it.

We observe a rise in the number of retweets and likes ordinary people earn for sharing domestic threat conspiracy theories after the war begins. Yet, ordinary people invoking foreign-threat conspiracy theories garner lower levels of predicted engagement after the full-scale invasion.

PiS officials invoking both foreign and domestic threat conspiracy theories earn higher levels of retweets and likes after the start of the war, compared with before the full-scale invasion.

Surprisingly, CTs with the greatest surge in Twitter engagement after the Russian invasion were those blaming domestic actors, not foreign actors. Domestic threat conspiracy theories may rise in times of foreign threat.

Conspiracy theories may not wane naturally. When a conspiracy theory’s threat frame is embedded in salient group divides, that CT may remain popular online. This effect strengthens when current events draw attention to those threats.

These findings are important because ethnopopulist politicians regularly exploit conspiracy theories in their rhetoric. Yet, these politicians are not automatically rewarded for doing so.

Our findings help establish when and how those politicians can expect support on social media when sharing these claims. When foreign and domestic threat frames appear more credible, associated conspiracy theories can surge in popularity.

Without events that reinforce the credibility of a conspiracy theory’s threat frames, politicians endorsing them may be punished online for sharing them.