President Trump refused to recognise the election result on the basis of unsubstantiated claims of electoral fraud. Twitter and Facebook took unprecedented initiatives against misinformation and false accusations, helping to safeguard American democracy, writes Angelo Vito Panaro

On 3 November 2020 Americans voted in Democrat Joe Biden as their 46th President, ousting the incumbent Republican President Donald Trump after his first term of office.

Despite polls predicting a ‘blue wave’ in Biden's favour, the election proved a nail-bitingly close competition, and confirmation of Biden’s victory did not happen until 8 November, five days after polling day.

President Trump exploited these five days of uncertainty by taking to social media, falsely claiming victory and calling into question the legitimacy of the electoral process. And he is still threatening lawsuits in various states to challenge the result.

Social media has, in this way, been dragged into politics. But this is not the first time. By 2019, Google, Twitter and Facebook were already being criticised for their inability to curb misinformation and do something about the proliferation of fake news in elections in Greece, Belgium, Ukraine and Estonia – and to the European Parliament. So how did social media perform this time?

In a democracy – as opposed to an autocracy – the incumbent gives up his political power if and when defeated in free and fair elections. President Trump, however, seems anything but willing to concede defeat, repeatedly claiming victory before all the votes had been counted.

Trump has questioned the validity of the elections, attacked millions of Americans who did not vote for him, claimed electoral fraud, and threated to go to the Supreme Court to have the result overturned.

Trump’s phraseology, unsubstantiated claims and refusal to concede reveal an autocratic streak which constitutes a threat to democracy. And most of his interventions have been communicated through his instrument of choice: social media.

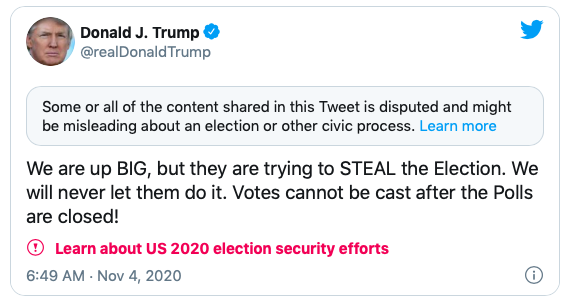

The day after the election, Trump used social media to claim victory before all votes had been counted. As counts continued in the battleground states of Pennsylvania, Nevada, Michigan and Georgia, Trump questioned their legitimacy, and repeatedly claimed 'electoral fraud' because, he argued, ballots received by mail after election day were not legal, and should not be counted.

The day after the election, Trump used social media to claim victory before all votes had been counted

Twitter intervened, flagging Trump’s tweets with warning labels stating that 'Some or all the content shared in this Tweet is disputed and might be misleading about the election or other civic process'. The company also blocked 20 tweets from the Georgia Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene, Eric Trump and Kayleigh McEnany, the White House press secretary who claimed Trump’s victory in Pennsylvania before it was revealed that he had, in fact, lost the State.

In a similar vein, Facebook, through a spokeswoman, declared that 'This period of heightened tension requires the adoption of exceptional measures'. The company implemented a new emergency plan to combat the misinformation and false accusations constantly reported on its platform.

'This period of heightened tension requires the adoption of exceptional measures'

FACEBOOK, NOVEMBER 2020

Facebook flagged Trump’s posts in which he claimed premature victory and aired accusations of electoral fraud. Initially, it labelled them 'See the latest updates in the 2020 US election'. But after half an hour, the company changed this to 'the final results may be different from initial vote counts, as ballot counting will continue for days or weeks'.

In the face of Trump's continued refusal to concede, Facebook then labelled his posts with a box emphasising the importance of respecting legal procedures and public institutions to ensure the integrity of American elections. It also banned the newly formed 'Stop the Steal' group of Trump supporters calling for 'boots on the ground to protect the integrity of the vote'.

In his 1971 book Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition, Robert Dahl argues that public contestation and electoral participation are the two pillars of democratic regimes. Once an incumbent is defeated through free and fair elections, he or she should leave office.

Trump’s unwillingness to recognise the result of this election, and to give up his office, threaten American democracy. While many institutions remained silent about Trump’s behaviour, Twitter and Facebook, have, in contrast with their responses to the various elections of 2019, taken assertive action to regulate the proliferation of misinformation from Trump and his followers.

Trump’s unwillingness to recognise the result of this election, and to give up his office, threaten American democracy

Some may argue that such emergency action represents an unwarranted intervention in domestic politics, to the point that social media companies could be branded political actors. But this is not the case. The 2020 American electoral experience shows that, while it is imperative to uphold freedom of expression, social media platforms have, at the same time, a responsibility to regulate the dissemination of misinformation and falsehoods.

In doing so, they act as an important safety net for democratic regimes, in the United States and around the world.