How do national stories shape voting behaviour? Odelia Oshri, Eran Amsalem, and Shaul Shenhav reveal that voters who view their nation through an exclusionary lens are more likely to support populist radical-right parties, especially those marginalised in society. Their findings highlight the powerful role of national narratives in driving political polarisation

Every nation has its own narratives about its history and imagined future. These stories play a crucial role in shaping national identity and political loyalties. But while national stories can unite people into a single community, they can also divide the nation and polarise politics.

Voters who view their nation’s history and future through a lens of conflict and exclusion – known as 'boundary national stories' – are much more likely to support populist radical-right parties. These national stories, which separate 'us' from 'them', resonate strongly with those who feel left behind by societal changes.

Voters who view their nation’s history and future through a lens of conflict and exclusion – known as 'boundary national stories' – are much more likely to support populist radical-right parties

In many democracies, the political landscape isn’t just split by the intensity of national sentiment. It is also polarised by fundamentally different understandings of the main building blocks of the nation, each rooted in distinct national stories.

For some, the most pivotal event in their nation’s history might be World War II. For others, it could be the achievement of women’s suffrage. Some dream of a more tolerant society, while others push for leaving the European Union or limiting immigration.

To understand these differences, we have categorised national stories into three broad categories:

The first two categories are based on the work of Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel in the World Value Survey. They reflect a spectrum of values in which self-expression emphasises autonomy and rights, while survival centres on economic and physical security.

The Boundary story, however, is distinct in that it defines the national community in terms of exclusion. It emphasises a division between 'us' and 'them'. Together, these three story-types mirror broad political divisions in advanced democracies.

Boundary stories often frame the nation’s history and future aspirations as a series of conflicts with external enemies

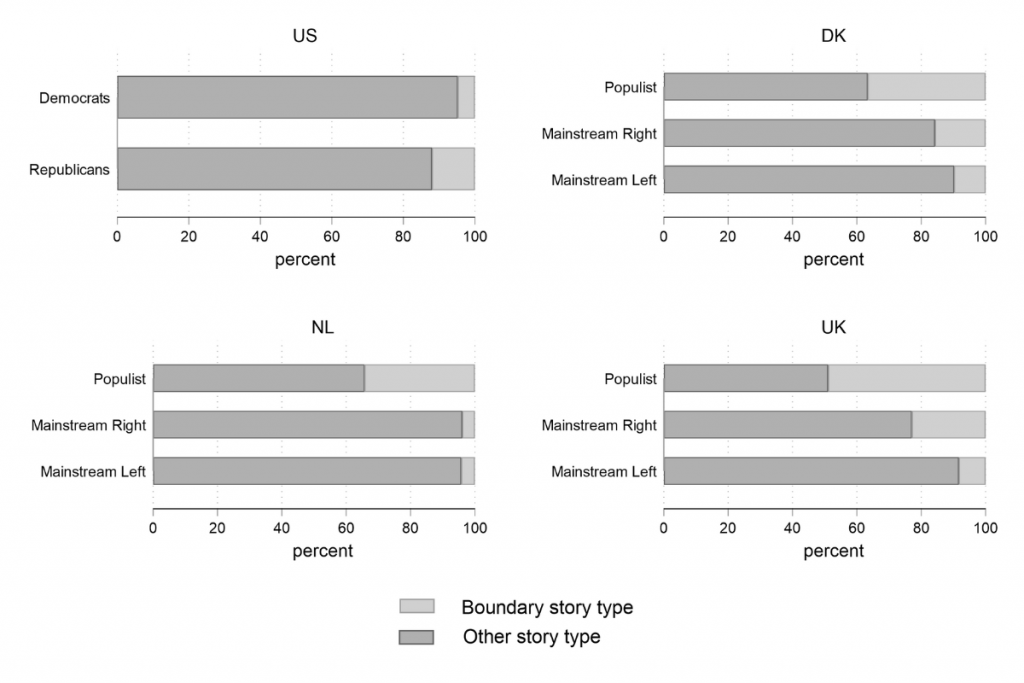

Surveys conducted in Denmark, the Netherlands, the UK, and the US reveal that supporters of populist radical-right parties are much more likely to embrace Boundary stories. For instance, Trump voters in the US often cite the September 11 attacks as a pivotal past event, while Danish populist-right voters point to the loss of South Jutland. These stories often frame the nation’s history and future aspirations as a series of conflicts with external enemies. In doing so, they reinforce a national identity rooted in exclusion. Conversely, supporters of mainstream parties tend to identify with Self-expression or Survival stories, which emphasise different aspects of national life.

Across all four countries, political conflicts primarily occur between the Self-expression and Boundary stories. The Survival story, however, plays a less significant role in partisan divisions.

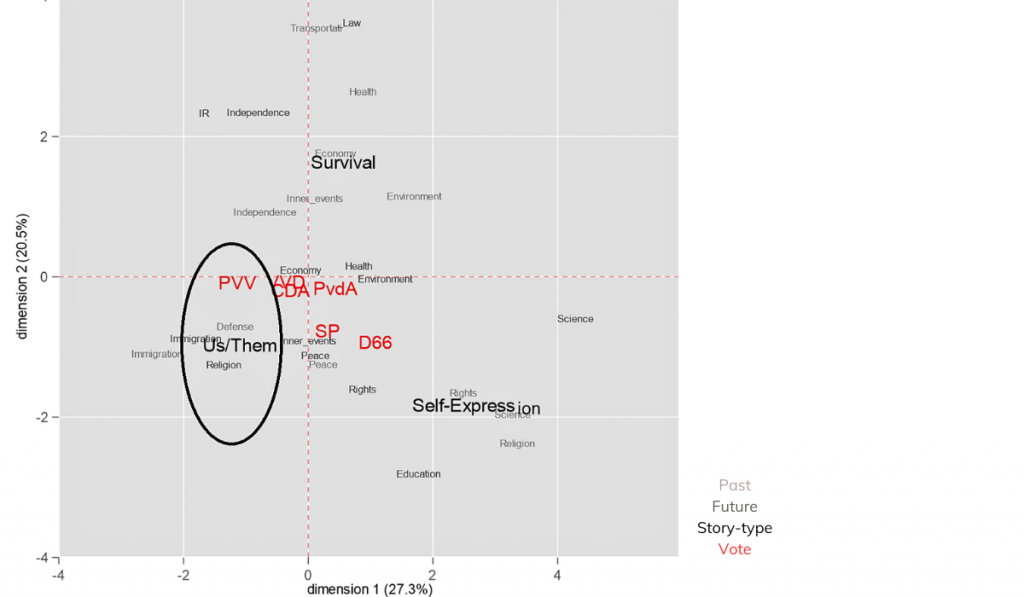

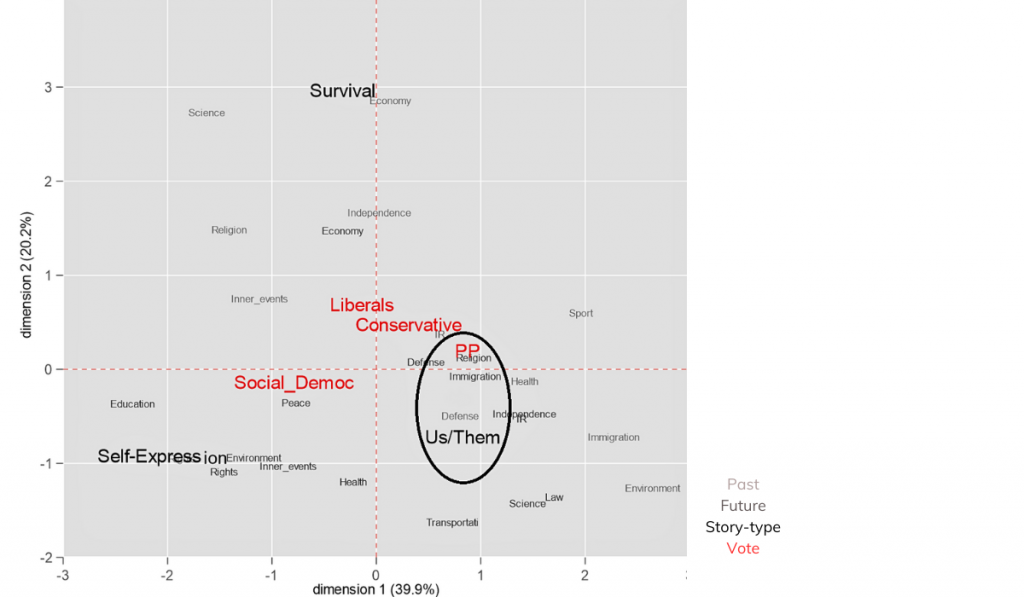

These graphs show the relationships between voting intentions, the most significant national past event, and future events respondents hope for. To pinpoint these descriptive correlations, we performed Multidimensional Correspondence Analysis, a method that maps relations that are active within a dataset by representing the distances between categorical variables in a smaller space: the closer the points on the plot, the more similar the stories and votes. This analysis helps examine how national stories differ between mainstream and populist party voters.

The Boundary and the Self-expression stories are located at the opposite poles of the first, horizontal, axis (thereby accounting for most of the variance), and thus they stand in competition. The Survival story, on the other hand, which focuses mainly on economic and security issues, is located on the vertical axis, and explains why there is less variance. This could suggest that the Survival story is less pertinent to partisan divisions, compared with the other two.

Is it possible that some voters who support mainstream parties also espouse the Boundary type of national story? And if so, what prevents them supporting populist radical-right parties? In other words, why doesn’t embracing an us-versus-them Boundary national story lead to votes for populist parties across the board?

As the graphs below illustrate, voters for mainstream parties do, in fact, hold Boundary national stories, though to a lesser extent than their populist counterparts. So, who are these mainstream right and left voters? Why is their vote 'shielded' from the electoral pull of the Boundary story-type? The answer lies in the combined effect of holding a Boundary national story and an individual's social positioning:

Our research shows that marginalised groups are more likely to translate this type of story into voting decisions. The Boundary story's influence on more privileged citizens is less potent.

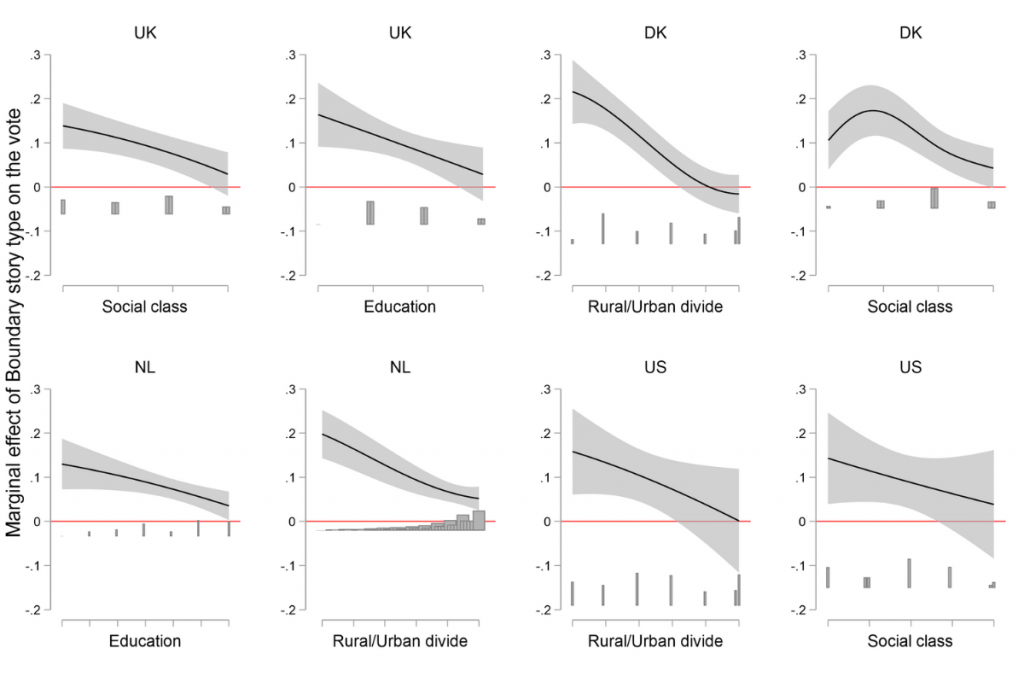

The graphs below display the marginal effect of the Boundary story on the vote for populist radical-right parties across different levels of education, social class, and residence (rural-versus-urban). The downward trend in all graphs suggests that the Boundary story has a significant effect on voting for these parties among the so-called 'left-behinders' – those who are less educated, economically disadvantaged, and residents of rural or peripheral areas. However, this effect diminishes among more privileged voters – the highly educated, the wealthy, and those living in big cities.

This might be because the Boundary story is central to the self-definition of those on the periphery, who may exclude others to strengthen their own sense of belonging.

By understanding people’s preferences regarding their nation’s past and future, we can better predict their electoral choices today

The findings highlight the power of national stories to shape voting behaviour across different political contexts. By understanding people’s preferences regarding their nation’s past and future, we can better predict their electoral choices today.

The graphs above shows the marginal effect of the us-versus-them Boundary story-type on the vote for populist radical-right parties (vertical axis) across levels of different socio-demographic variables. Marked are 95% confidence intervals. All moderating variables (on the x axis) span from marginalised groups to more privileged voters. The social class variable spans from working to upper class; education spans from 12 or 13 years of age or younger to graduate and postgraduate; and Rural/Urban spans from those living in rural areas to those living in cities with over one million inhabitants.

These findings underscore how economic grievances and cultural narratives coalesce into support for populist radical-right parties. National stories, while building group cohesion, also have the potential to deepen political polarisation. This is a dynamic that deserves more attention from political behaviour researchers.