Often labelled technocratic and expertise-driven, the Commission’s ‘unelected bureaucrats’ in fact take public opinion seriously. When facing crises, the Commission uses agenda-priorities to respond to citizens’ cues, write Christel Koop, Christine Reh and Edoardo Bressanelli

Over the past decade, the European Union has faced intense political pressure and undergone a string of existential crises. Europe’s citizens have voiced their concerns about and dissatisfaction with the EU. They voted in larger numbers for Eurosceptic parties, resisted further integration and, in one country, even opted to leave the Union.

Not long ago, Europe’s citizens hardly featured for the Commission. In fact, citizens themselves looked at all matters European from a distance. This situation was famously labelled as permissive consensus: the Commission advanced market integration; citizens by and large supported the EU, which for them was of low salience.

Yet, in 1993, the Maastricht Treaty moved integration beyond the economic. Citizens realised increasingly that Europe mattered – especially when EU countries were hit by the economic downturn, the so-called refugee crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic. Permissive consensus gave way to constraining dissensus. The EU became contested across its member states, and public and political opposition acted as a brake on further integration.

After the Maastricht Treaty, citizens realised increasingly that Europe mattered – especially when EU countries were hit by crisis

But such politicisation doesn't always halt integration. In some circumstances, dissensus can actually enable EU institutions to exploit contestation to their own advantage. Capitalising on popular dissatisfaction with the status quo, institutions can seek further integration, and to transfer policy competences to the EU. In the process, they expand their own powers.

The European Commission is a case in point. Once the epitome of technocracy (unelected, neutral, expertise-driven), the new political environment no longer allowed the Commission to rely on business as usual. As the public face of ‘Brussels’, the Commission has been at the centre of Eurosceptic attacks and calls for more supranational action. In such a context, it became harder for the Commission to continue focusing on its established audience of experts, stakeholders, and insider networks.

Instead, the Commission turned to the wider public. To signal responsiveness to (sometimes countervailing) public pressures, the Commission has an important tool at its disposal: the near-exclusive monopoly of legislative initiative. Following up on its overall political programme, the Commission’s annual work programmes present its legislative plans for the twelve months to come. Work programmes also indicate which proposals should be prioritised, or withdrawn.

By doing so, the Commission tells citizens, member states and stakeholders what it considers to matter most, even though the legislation itself is subsequently negotiated by member states in the Council and political parties in the European Parliament.

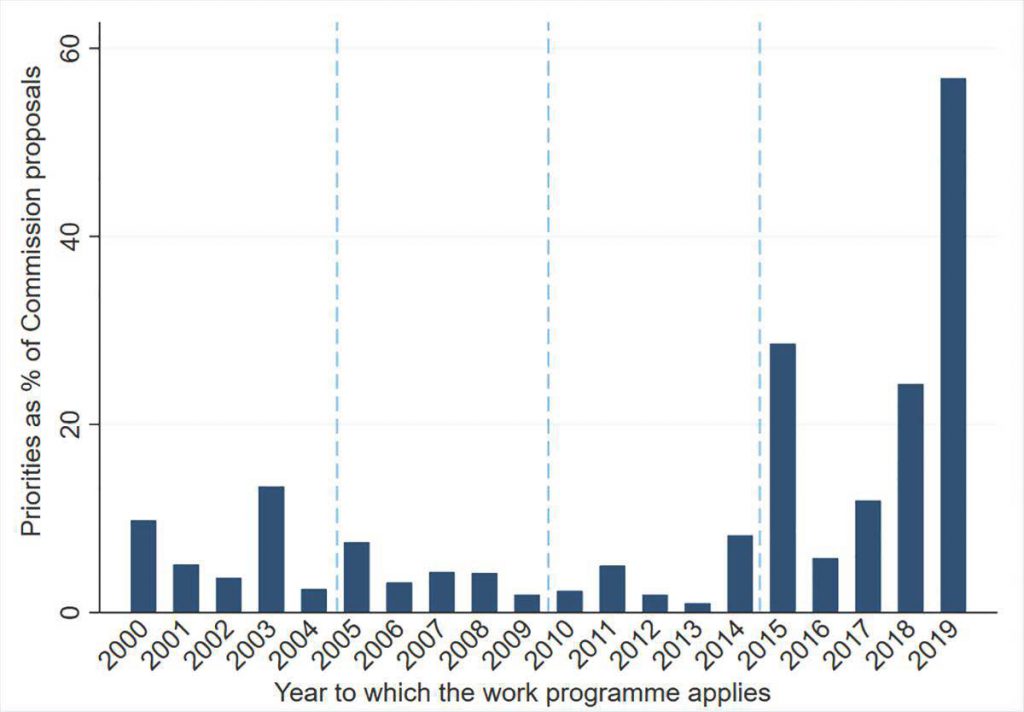

Legislative programming is not new – the Commission started using it in the late 1990s. Yet programming has become more structured and sophisticated over time. In the EU’s very first State of the Union speech, then Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker pitched the idea of a ‘political Commission’ (or, as he put it, a ‘very political’ Commission). Such an executive would be committed to setting and pushing priorities, and to monitoring their implementation. During his term in office, Juncker, accordingly, attributed a central role to legislative priorities (see Figure 1), and implemented most of his strategic plan.

Jean-Claude Juncker

European Policy Centre Thought Leadership Forum, 24 October 2019

Juncker himself said his Commission was guided by citizens' ideas. But does the Commission take citizens’ input on board when it sets legislative priorities?

We analysed the Commission’s legislative agenda from 1999 to 2019 – covering almost 2,000 laws and the mandates of four Presidents. The results of our research show that the Commission does indeed listen to citizens' views.

In particular, the Commission’s agenda responds to public salience. Policy issues important to Europe’s citizens are more likely to become legislative priorities. President Juncker, especially, prioritised legislation more than his predecessors. But this is not (only) a story about the Juncker Commission. Citizens’ concerns have shaped the Commission’s agenda at least since the early 2000s.

The impact of public issue salience on the Commission’s priority-setting is strong and robust

Under growing contestation, the Commission promotes legislation that matters to citizens. What is more, Euroscepticism does not constrain the Commission in its priority-setting – even though the Commission is more likely to take legislative proposals off the table when Europe’s citizens become more hostile to the Union.

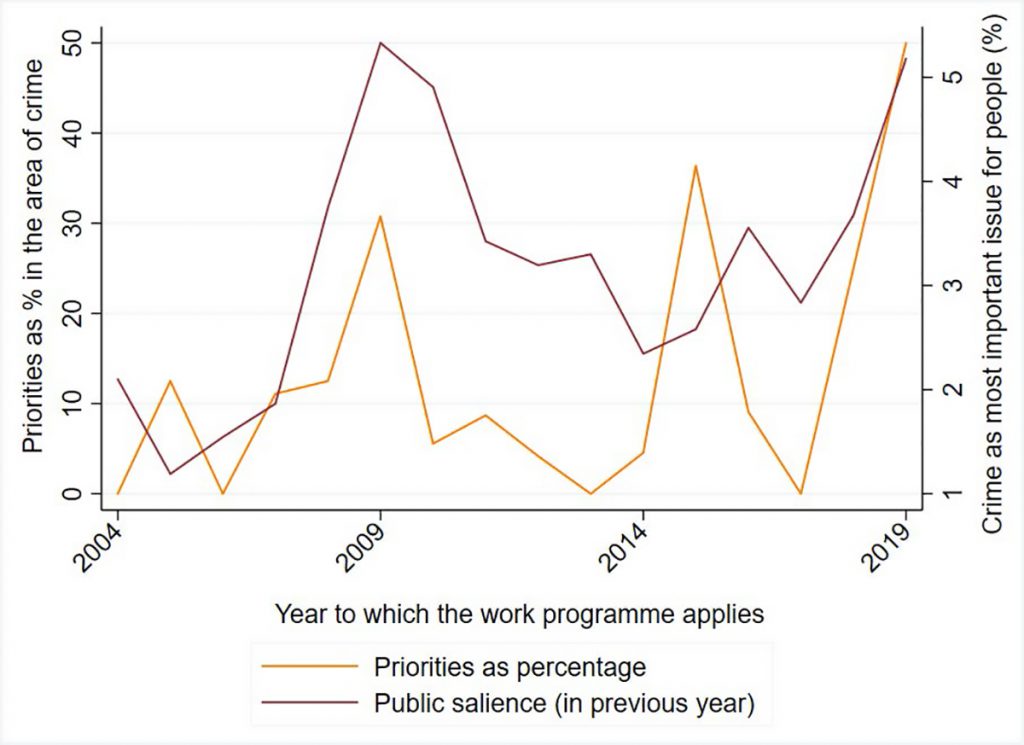

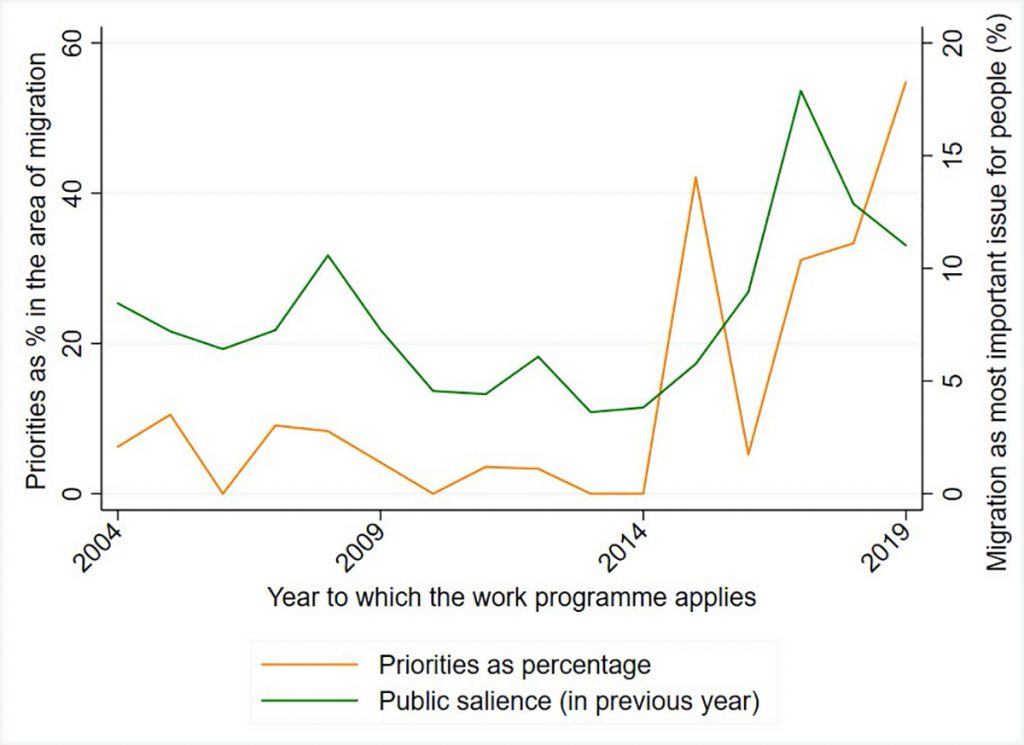

Figures 2 and 3 show issue salience expressed in public opinion, and the share of priorities, in two specific policy fields. In the area of crime, spikes in the two lines mirror each other nicely. In the field of migration, the huge increase in public salience corresponds to a spike in priority-setting by the Juncker Commission. Systematic analysis confirms that the impact of public issue salience on the Commission’s priority-setting is strong and robust.

These findings matter because they suggest that the Commission’s ‘unelected bureaucrats’ take public opinion very seriously. Notwithstanding the executive’s tenuous electoral mandate, the Commission’s agenda responds to citizens’ cues. This happens despite – or, perhaps, because of – entrenched Euroscepticism and the Union’s politicisation across member states.

Gone are the days of a technocratic European Commission, shielded from public pressure by permissive consensus

Our argument, underscored in interviews we conducted in Brussels, is in line with earlier research on public opinion and the Commission. The trend continues with the von der Leyen Commission. Shortly after taking office in 2019, von der Leyen adjusted her first work programme in the then-evolving Covid-19 crisis, to ‘take on board the views of citizens’ and to produce ‘tangible results’.

Long gone are the days of a technocratic European Commission, shielded from public pressure by permissive consensus. Yet we show that contestation has not constrained Europe’s executive.

The Commission continues to provide technical expertise and to broker compromise. But it also uses agenda-priorities to signal visibly its quest for policy outputs that matter the most to Europe’s citizens.

[…] The European Commission is no longer technocratic – it takes public opinion seriously […]