Germany's Die Linke is one of the most established left-wing populist parties in Europe. But if Sahra Wagenknecht breaks away to form her own party, it may soon experience a split. Jan Philipp Thomeczek considers the situation in the German historical context, and in the context of populist movements more broadly

In contemporary Europe, the populist radical right poses a great threat to liberal democracy. This is most striking in Poland and Hungary, where the populist radical right has eroded liberal-democratic principles since it took power.

However, we should not reduce populism to the radical right alone. Populist ideas are also frequently combined with core ideas of radical-left ideology, which are economic egalitarianism and anti-capitalism. Although this party family has experienced setbacks in recent elections across Europe, we should not write it off. We know from Greece's recent history that economic crises create fertile ground for left-wing populist narratives. This is highly relevant because Europe currently faces record-high inflation rates.

Economic crises create fertile ground for left-wing populist narratives

One of the most established left-wing populist parties in Europe is the German Die Linke (The Left). Its long-term success, great internal heterogeneity, and precarious future make it a worthy case for us to study more closely.

Left-wing populism in Germany made its first significant appearance after reunification. With the Bundestag elections in 1990, the Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus (PDS), which evolved out of the German Democratic Republic’s Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED), entered the new unified German party system. The PDS embodied core populist ideas. It often framed them against the backdrop of the East-West divide and pitted the West German economic elite against the East German people.

PDS was established in East Germany and failed to win seats in any West German state elections. Its main problem was that it could not attract voters outside West Germany's communist milieu.

Thus, in 2007, the party merged with the West German SPD splinter group Electoral Alternative for Labour and Social Justice (WASG), to form a party under the new name Die Linke. Internally, this strengthened the radical wing. Many West German WASG members came from smaller communist parties or unions, and the common denominator was opposition to the SPD’s labour market reforms. Consequently, the influence of moderate PDS members, who already had government experience in some East German states, was weakened.

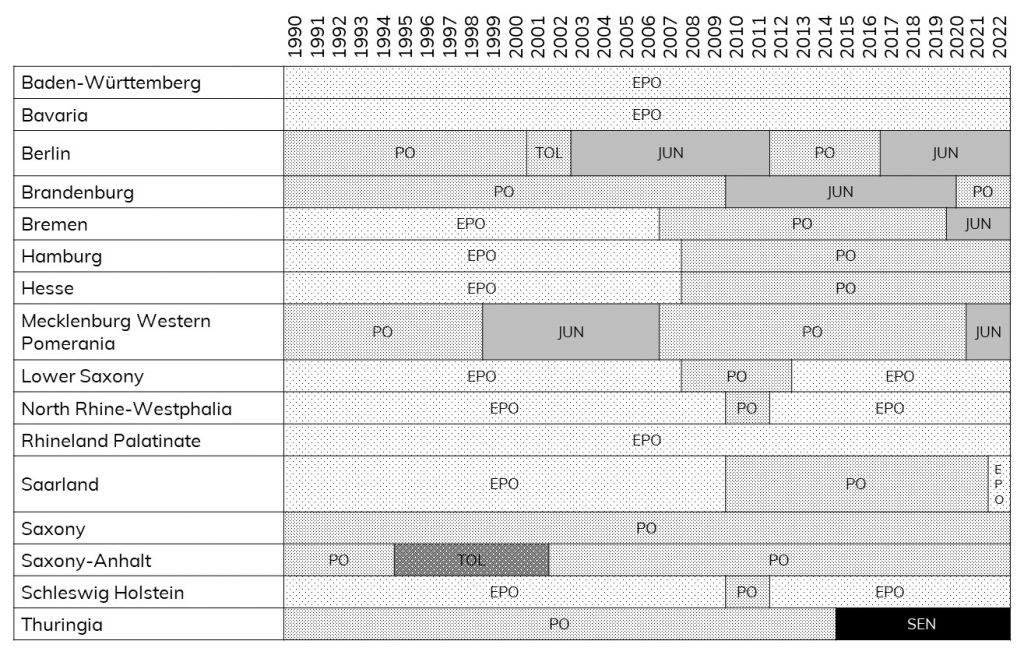

The party’s division is best exemplified by looking at the sixteen German state chapters. In East German states, where Die Linke has much government experience, the party tends to be less radical. Die Linke is most established in Thuringia, where its leader Bodo Ramelow has led the state government since 2014. Some have openly questioned whether the party should still be classified as populist in Thuringia, and some Christian Democrats have even suggested they might consider a coalition with Die Linke after the next election to weaken the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD).

Die Linke holds vastly different positions in West and East German states, and has correspondingly different outlooks

In West Germany, the situation is entirely different. The party is (still) monitored by some West German State Offices for the Protection of the Constitution. In most West German states, Die Linke is currently in extra-parliamentary opposition, and in three, the party has never held any seats. An exception is Bremen, where Die Linke has been governing since 2019. In a recent article, I show how the state chapter’s position in government or opposition also affects its level of populist rhetoric. The party chapters in opposition use populist communication elements more frequently than those in power.

Seventeen years ago, Michael Koß and Dan Hough described the PDS as an 'exceptionally heterogeneous party'. However, Die Linke’s current internal struggle is even more profound. Former co-faction leader Sahra Wagenknecht, who is exceptionally popular among the German electorate, has been contemplating founding her own party. And, recently, Die Linke's federal board asked Wagenknecht to step down from her position as MP, a request she left unanswered.

Wagenknecht feels Die Linke has become far too progressive on climate and immigration policy. This makes her appealing to left-wing authoritarian voters

Wagenknecht, who uses populist rhetoric frequently, says that Die Linke has become far too progressive regarding climate and immigration policies. Our recent analysis shows that she can appeal to left-wing authoritarian voters. A new Wagenknecht party might even attract voters away from the AfD.

In the 2021 Bundestag elections, Die Linke won less than 5% of the votes. And according to recent polls, it seems it would rather suffer further losses than win over new voters. In a situation where Die Linke needs every vote to survive, Wagenknecht’s new party could attract a crucial sector of its electorate.

However, the party is too established in the Eastern states to vanish entirely from the political landscape. Thus, the new Wagenknecht party could force a party split.

The Wagenknecht case reminds us of the personalisation of populist parties. Some go so far as to identify the presence of a charismatic leader as a necessary condition for populism. There is, at least, no doubt that the most successful populist parties in Europe profit electorally from the popularity of their long-term leaders. Prominent examples are Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders, Viktor Orbán and Matteo Salvini. A new Wagenknecht party could, thus, be another example of a highly personalised populist party.

However, Die Linke’s struggle also reminds us of the historical and ongoing struggles within the far left, which run the gamut from communists and socialists, to populists and non-populists, and radicals and extremists, to name just a few dividing lines. France is one example in which the build-up of a broad (populist) far-left movement works rather well. In Germany, by contrast, a new Wagenknecht party, rather than uniting the German political left, would likely increase polarisation, and deepen the existing divide.

43 in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more