What does a coastline have in common with effective rhetoric? Each component resembles something bigger, and bigger, and bigger. And what can this sort of fractal pattern show us about politics? To Alex Prior, fractals illustrate successful representation, and the impulses that drive it

In launching the ‘Science of Democracy’ blog series, Jean-Paul Gagnon argues that democracy’s words require a new narrative. Agustín Goenaga credits Gagnon with a ‘living archive’ of stories. As I have argued previously, the best way of understanding narratives and stories – and their importance to democracy – is through their fractal nature.

Fractals are patterns; we see them constantly. They are in trees, lightning, coastlines. If you zoom in on any of those images, they still resemble themselves. This is self-similarity, a defining characteristic of fractals.

Self-similarity is a defining characteristic of fractals and of representation, which makes present what is not physically there

It is also a characteristic of representation (in its many forms): ‘making something present’, typically by acting on something or someone’s behalf. The notion that we can make present what is not physically there (a constituency, an idea, or anything else) is central to my research on parliamentary systems. Such systems depend on representatives making others’ voices and values present.

Self-similarity – and recursion (the repetition of a structure with continual reference, at each stage, to the structure itself) – is applicable to politics in many ways. For example, some advocate ‘fractal democracy’ as a practical model of governance. Says Jasper Sky: 'Groups of seven people each choose one representative, and those seven representatives then meet to choose a representative, and so on, up several levels of representation…[with] the person at the top of the fractal hierarchy to be held fully accountable at every level.'

Fractals also give us a conceptual framework for politics. 'Fractal politics', writes Gordon Fletcher, 'reflects the sociological sensibility that people seek out self-similarity in the form of opinions and worldviews that align with their own identity'. Fractals can help us understand not only political communication and support, but the ways in which we interact with our own social reality.

But how can we study (or even conceptualise) these opinions and those who ‘make’ them? And what does it really mean to seek out self-similarity (i.e., to seek ourselves) in the opinions and worldviews of others? The answer to both questions lies in representation.

Fractals can be read into theoretical works on representation, such as those of Derrida, who contends that '[e]verything begins by referring back (par le renvoi), that is to say, does not begin'. Derrida’s description centres around self-similarity and recursion (‘referring back’), as well as infinite replicability (‘does not begin’).

So far, so fractal. But fractals are even more relevant to contemporary representation theory. Saward’s theory of the representative claim identifies how '[m]akers of representative claims suggest to the potential audience: (1) you are/are part of this audience, (2) you should accept this view, this construction — this representation — of yourself, and (3) you should accept me as speaking and acting for you.'

Representation is a ‘claim’ made to an audience about the maker of the claim (a politician, for example), about what they ‘stand for’, and about that audience

Saward shows us how representation works. It is a ‘claim’ (or a series of claims) made to an audience about the maker of the claim (a politician, for example), about what they ‘stand for’, and about that audience.

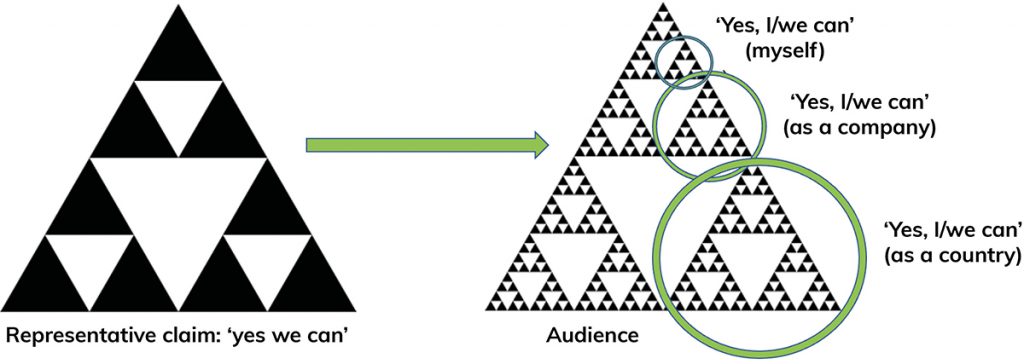

A representative claim can be made at different scales (e.g., to a person, a group, a region), sometimes simultaneously. It is also accepted or rejected (i.e., interpreted) by audiences at many different scales (e.g., myself as an individual, as a citizen, as a person, etc). Fractals are invaluable in helping to conceptualise the way that representative claims in politics and beyond connect (or fail to connect) with their audience.

Consider Obama’s effective 'yes we can' 2008 slogan. People saw themselves within this slogan, at many (potentially infinite) scales:

The left image resembles the right image at every scale. Effective representative claims resemble the audience at every level; audience members identify themselves within (with/in) the claim. We thereby read effective representative claims as successful appeals to self-similarity.

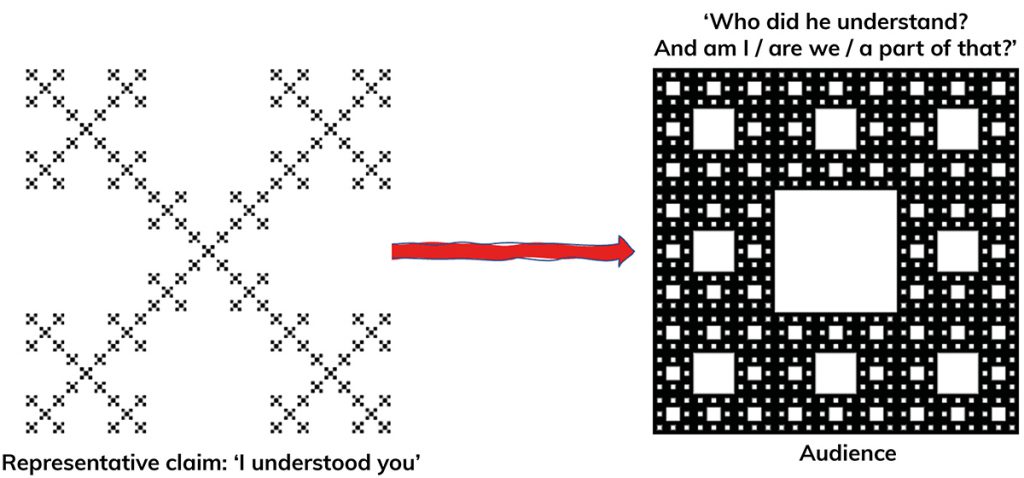

This process is not always successful. On 4 June 1958, against the backdrop of the Algerian War of Independence and the collapse of the Fourth Republic, Charles De Gaulle arrived in Algiers and uttered the famous words Je vous ai compris! [I understood you!]. To this day it is unclear who De Gaulle was addressing: Algerians? French Algeria? Colonists? The military?

The failure of this representative claim lies in a failed appeal to self-similarity. It failed to reflect (or even define) an audience at any scale.

Self-similarity matters for the maker of the representative claim, not just the audience. Obama included himself ('we') in a claim of common purpose, with/in which the audience recognised themselves. De Gaulle’s claim ('I understood you') lacks self-similarity. Audience members were left wondering who ‘they’ were, who De Gaulle was, and who/what he ‘stood for’.

The mathematician Edward Norton Lorenz is closely associated with chaos theory and the ‘butterfly effect’, by which small initial variations eventually yield drastic outcomes. For example – a person writes a short essay in Canberra; later, I see a broad and rich international academic debate. Fractals are a component of chaos, and a means of visualising it.

Studying representation in action (via fractals) clarifies the appeal of self-similarity, and why some statements are all-encompassing in their alienation

They also provide a means of studying narratives and stories within a ‘science of democracy’. Moreover, studying representation in action (via fractals) clarifies the appeal of self-similarity. We seek patterns, and we seek ourselves. This matters in terms of content and context. Alongside the political statements and patterns discussed earlier, consider that Obama reflected an audience ('we') descriptively and symbolically, in a way that De Gaulle could not, and arguably never claimed to ('I…you').

Fractals show us how ambiguous (but ostensibly all-encompassing) political and other statements are, in practice. They are all-encompassing only inasmuch as they alienate everyone at the same time. This mattered in 1958, it mattered in 2008, and it matters today.

Number 56 in a Loop thread on the science of democracy. Look out for the 🦋 to read more in our series