We know that there is an inherent tension between populism and liberal democracy. So how does this translate into law when populists are in power? Jasmin Sarah König and Tilko Swalve argue that constitutional changes by populist governments can have ambiguous implications for democratic quality

Populism stands in conflict with two key features of liberal democracy: pluralism and minority rights. This is one of populism's most-discussed defining features, and one that Petra Guasti and Mattia Zulianello touch upon in their inaugural post in this series.

The tension between populism and liberal democratic values lies at the heart of populist ideology. The idea of a homogenous ‘people’ with a unified will as the only legitimate input in the political decision-making process is at odds with the system of checks and balances in liberal democracies. Ideas such as minority rights, pluralism, and power-sharing are central to liberal democracy, and often enshrined in a country’s constitution.

The idea of a homogenous ‘people’ with a unified will as the only legitimate input in the political decision-making process is at odds with the system of checks and balances in liberal democracies

This often leads to the assumption that populists use constitutional changes to consolidate their power and dismantle democracy. We call this phenomenon ‘constitutional regression’.

Recent events such as the 6 January US Capitol attack, the PiS party’s disregard for judicial rulings in Poland, or Netanyahu’s attempt to curb judicial power in Israel speak volumes on the threat populists can pose to constitutional democracy.

But some argue that the populist approach to constitutionalism is not undemocratic. Rather, they say, it is simply a different idea of democracy, one that views the constitution as a living document that changes with the people’s general will.

What happens around the world when populists change constitutions? In our recent EJPR paper, we conducted an empirical analysis of the relationship between populists in government, constitutional changes, and democratic quality. We argue that the relationship between populism and constitutional regression is anything but clear-cut, and requires further investigation.

To do this, we focused on democracies in Europe and Latin America. We estimate the effect of constitutional changes, firstly on the quality of liberal democratic institutions, and secondly on participation, conditional on the degree of populism in the government.

To explore the data, we have created an interactive tool that allows users to see how constitutional changes under populist governments have affected different aspects of democracy in the countries included in our study. It shows that the effects of constitutional changes on democracy differ between contexts.

Constitutional changes implemented by populist governments can have quite different effects on liberal democracy and participation depending on the context

After choosing a country, you can decide between three different data sets on populism. In some cases, we also allow you to choose how populism in government should be calculated. The options are government mean populism score, government weighted populism score, head of state populism score, or scoring only by senior party. In the last step, you can choose which democracy indices from the V-Dem dataset you want to explore. We added three more indices in this tool that do not appear in our paper.

Our software allows users to track constitutional changes and their correlation with different indices of democratic quality in a variety of countries. The tool embedded below is for use only on a desktop computer. Use this one if you're reading on a mobile device.

Overall, the data reveal a complex relationship between populism, constitutionalism, and the quality of liberal democracy.

Constitutional changes under populist governments in Hungary were, obviously, detrimental to liberal democratic quality. But in countries such as Costa Rica, or Ecuador, the relationship appears more ambiguous. In Costa Rica, the populist government does not seem to have had a lasting impact on democratic quality, while in Ecuador, a populist government was responsible for a strong decrease in democratic quality, as well as its subsequent recovery.

What does exploration of the data show? Primarily, that we should be careful not to infer a general causal relationship between populism and constitutional regression from a few salient cases. Constitutional changes in the US, Hungary, Poland, and Israel are worrisome with respect to the quality of liberal democracy. But we are more likely to pay attention to cases in which populists have used (or tried to use) constitutional changes to dismantle liberal democracy than those where they have not.

This is also reflected in our analysis. To operationalise liberal democratic quality, we employ V-Dem’s liberal component index (LCI) and the participatory index (PCI) to measure participation. Data on constitutional changes comes from the Comparative Constitutions Project. The government’s degree of populism is operationalised as V-Party’s populism score, which we weigh by the respective party’s strength in government.

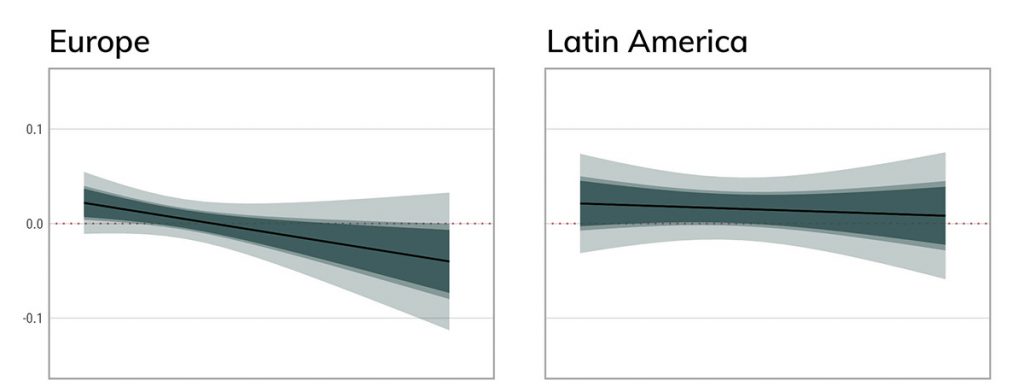

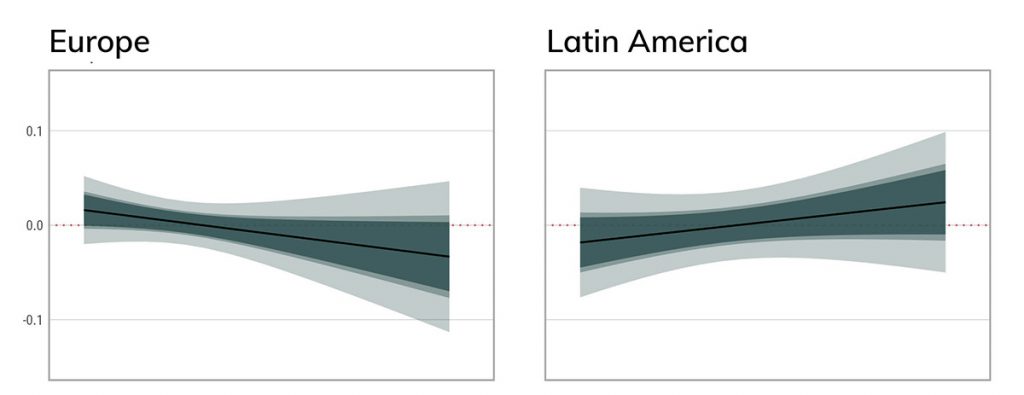

We visualise our results in the conditional-effect plot below. The findings demonstrate that constitutional changes implemented by populist governments can bring quite different effects to bear on liberal democracy and participation, depending on the context.

Populists in power in Latin America have, overall and contrary to expectations, implemented constitutional changes that improved liberal democratic institutions. But their changes failed to improve the quality of participatory democracy overall.

In Europe, on the other hand, populists have used constitutional changes to decrease the quality of both democratic characteristics.

The effect of constitutional changes under populist governments differs substantially between Latin America and Europe

Our results speak to the findings of many other papers that demonstrate the extent of the variance between populist parties’ behaviour toward democracy. These findings imply that it is not only populist ideology driving governments' use of constitutional changes.

What other forces drive this, exactly, cannot be answered by our research right now. However, existing scholarship points to the host ideologies, the political system, or to a country’s previous democratic quality as potential explanations.

Our research finds that the effect of constitutional changes under populist governments differs substantially between Latin America and Europe. European populists cause participatory democracy to decline – and they tend to worsen the quality of liberal democracy, too. The effects in Latin America, meanwhile, are more complex.

This ambiguous relationship between populism and constitutionalism points towards a larger gap in populism research. While we now know more about populist voters, populist policy positions, and rhetoric, we still know relatively little about if, when, and how populist governments translate their ideology into law.

So far, our knowledge on the intersection between populism and constitutionalism comes from a few salient cases. However, many of these cases involve parties who are not just populist: they are also far right. We propose more research at the intersection between populism and legal research. As a first step, we are investigating the use of judicial review as a measure of populist government performance.

35 in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more