Luca Versteegen argues that specific emotions like nostalgia are not limited to populist radical-right voters. We should therefore be more careful in ascribing emotions to this group, differentiating emotions and refraining from broad ascriptions like the so-called ‘left behind’

With the rise of populist radical-right parties across the globe, we have seen an explosion of attempts to explain their success. These parties’ voters are often of particular interest. Who are they? What do they think? What do they feel?

Such questions often carry an undertone: what is wrong with these people? Researchers, journalists, and voters for other parties have put forward many ideas.

As Mattia Zulianello and Petra Guasti point out in this series, there are several myths surrounding populism. Many concern these parties’ ideologies or issue positions. But besides this, some of these myths concern populist radical-right voters themselves.

One common myth presents these voters as the left behind. But it remains unclear what left behind means, let alone whether this is an accurate description – or even whether it applies only to populist radical-right voters.

Who are the left behind? To some observers, it means those living in isolated regions who politicians largely ignore in their decision-making. Others suggest it describes people whose traditional, materialistic values seem weirdly misplaced in a modern, post-materialist world.

Often, scholars think of this group as people who experience or anticipate an economic decline. The latter explanation is concerned with status loss, the experience or concern that oneself or one’s group will be worse off than in the past. Importantly, radical-right voters are not necessarily those who have lost. They often simply fear that they could lose their wealth or privilege in the future.

All these explanations matter to some extent. But, increasingly, researchers are trying to dig deeper into radical-right voters’ perceptions, thoughts, and feelings. Their research shows, for example, that anger and resentment drive support for these parties, and how radical-right rhetoric fuels anger, fear, disgust, and sadness.

Slogans like 'Make America Great Again' and 'Take Back Control' reflect the nostalgic longing for a traditional, culturally homogeneous societal past

But beyond that, emotions can be another way to describe the left behind. So, are certain emotions particularly prevalent among members of this group?

One emotion that comes to mind is nostalgia, a rose-tinted longing for the past. Left-behind people, so the idea goes, are those who constantly dream of the past as a golden era or the glory days. Intuitively, radical-right parties’ pledges to 'Make America Great Again' or 'Take Back Control' fit nicely with the image of left-behind voters longing for the good old days.

Unsurprisingly, scholars have examined individuals’ nostalgia and migration attitudes, nostalgia and populism, and politicians’ nostalgic rhetoric. But is nostalgia really so unique to populist radical-right voters?

In my recent EJPR article, I examined the prevalence and contents of nostalgia using representative panel data. Who experiences nostalgia? How often? And what do people actually long for? To answer these questions, I used data from more than 10,000 people in the Netherlands.

Almost two-thirds of Dutch respondents experience nostalgia each month

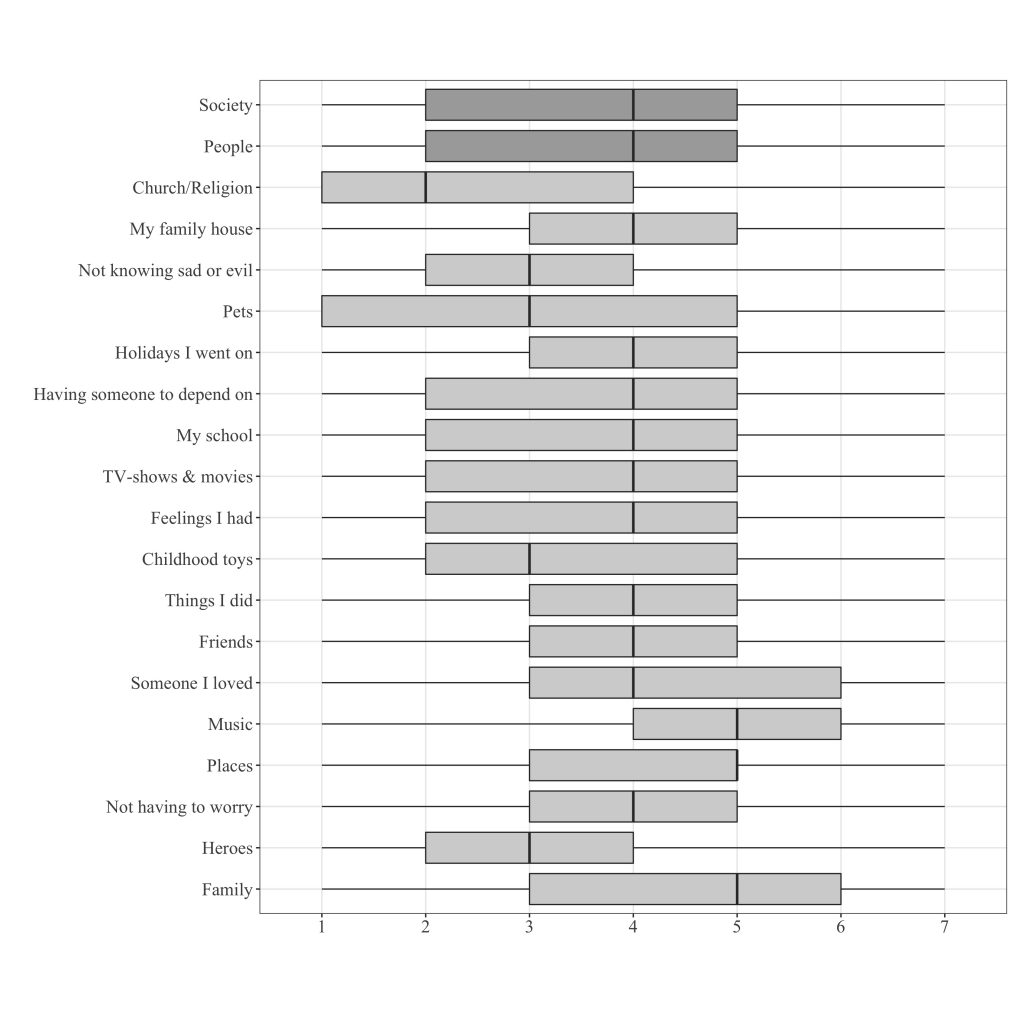

I found that people longed for many different things. Most notably, they longed for music, family memories, or places they have been to. See the graph below. Church or religion were less often the subject of nostalgia.

Besides this variety of content, I found that nostalgia was frequent! About 61% of the sample experienced nostalgia at least once or twice a month. There were differences between education, occupation, and gender groups. But, generally, nostalgia was a common emotion.

But is nostalgia particularly common among radical-right voters? That is, do the purported left behind experience nostalgia particularly often or experience specific types of nostalgia?

The answer is yes, but it is nuanced. Radical-right voters tend to be particularly nostalgic about societal conditions, such as the way society was or the way people were. This likely reflects their preferences for the more traditional, homogeneous societies of the past.

They also tend to be more nostalgic about personal matters (e.g., family, music, pets), but this relationship is much weaker. When differentiating these group-based and personal forms of nostalgia, only the former predicts radical-right vote propensity, sympathy towards these parties and politicians, and conservatism.

Only group-based forms of nostalgia, as opposed to personal nostalgia, predict support for the radical right

In sum, we must be careful about drawing any conclusion that populist radical-right voters, the alleged left behind, are distinct in their longing for the past. My results suggest a more nuanced answer. Longing for the societal past motivates support for the populist radical right, but nostalgia about the personal past is common across voters in all camps.

First, we must be more careful when ascribing nostalgia to populist radical-right voters. It is true that nostalgia plays a role in motivating this ideology, but this emotion is not unique to this electorate.

Second, my findings call for nuance when explaining these voters’ emotions. Observers tend to lump together various emotions like fear, anger, or resentment. This ignores the fact that different emotions predict different behaviours, and that only some of these emotions matter to the radical right.

Third, we need to ask ourselves whether broad ascriptions like the left behind have much use. Yes, it is vital to explain support for these parties. But myths that isolate them from a purported mainstream may just further fan the flames.

Ultimately, conceiving radical-right voters – including their emotions – as not so different from the rest may also be good news. If we share specific emotional experiences, this can unite us. If most of us long for our childhood from time to time, why not share these memories, and perhaps find common ground therein?

23rd in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more