Over time, European party systems develop ‘closure’, meaning predictable relations among a stable set of parties. Zsolt Enyedi and Fernando Casal Bértoa analyse how this happens, and what impact it has on European democracy

We are living in times of intense political challenge and conflict, especially with the rise of anti-establishment populist parties. Almost all scholarly attention tends to focus on the degree of change in party systems. By contrast, scholars have devoted very little attention to stability and predictability in these systems.

It's an anomaly we address in our recently published book. Employing an innovative dataset going back to 1848, we classify all European democratic party systems according to their level of ‘closure’, understood as predictable relations among a stable set of political parties.

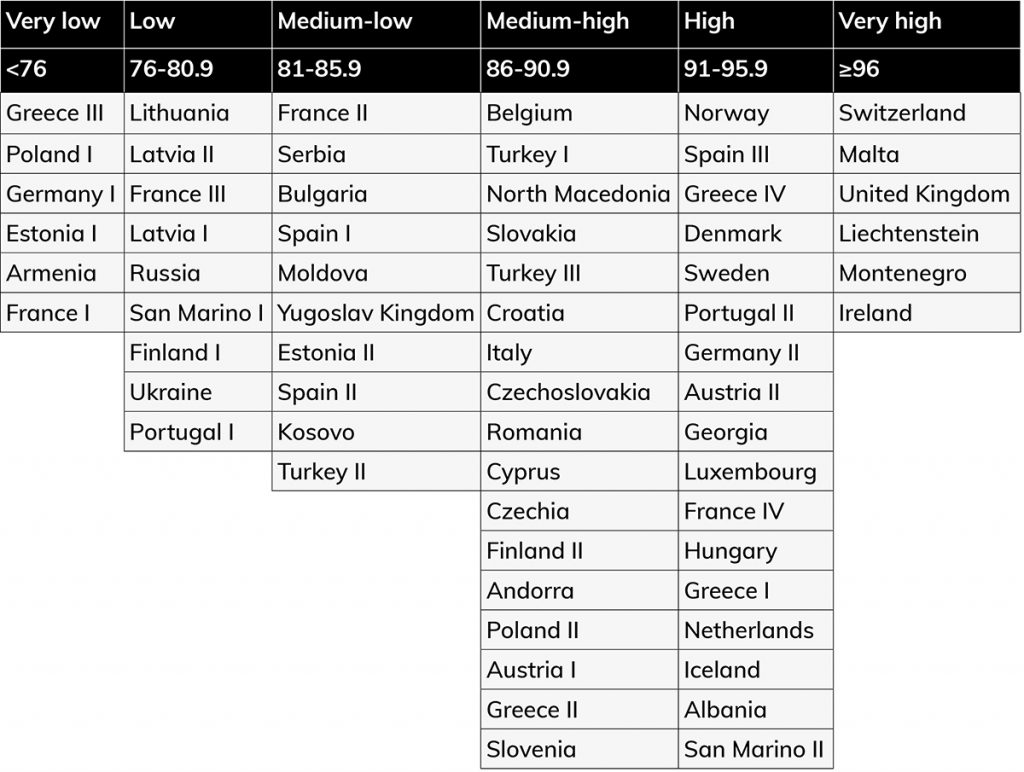

We use a new operationalisation of party system closure developed on the basis of the notion introduced by Peter Mair in the late 1990s. It examines the structure and institutionalisation of inter-party competition in 65 party systems. These include macro- and micro-states, pre-WWII and post-1945 democracies as well as Western, Southern and Eastern European countries.

As the table shows, most historical regimes are at the more ‘open’ end of the ranking (to the left of the table), joined by post-communist Latvia and Lithuania. In contrast, southern European and most pre-WWI Western European democracies have comparatively stable party systems.

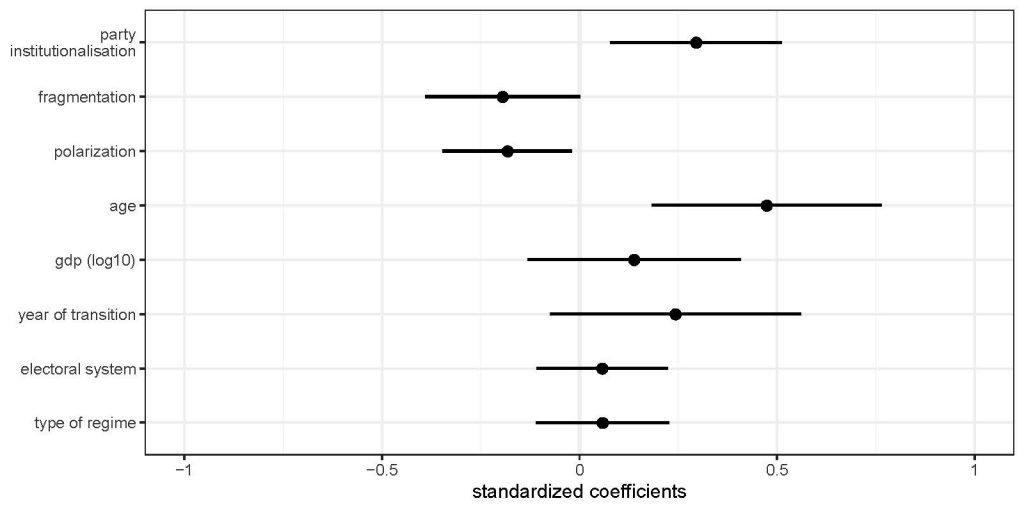

Four main factors explain party system closure: the age of the democratic party system, party institutionalisation, fragmentation, and polarisation (measured as electoral support for anti-establishment parties).

the more electorally successful anti-establishment parties are in a system, the less stable and predictable party systems will be

Among these variables, the age of the democratic party system stands out – see the figure below. Because of the socialisation process of both voters and political elites in terms of voting and coalitional behaviours, the longer a party system remains democratic, the greater the predictability of partisan interactions.

As follows from the figure above, the institutionalisation of political parties as socially rooted and stable organisations also has a significant impact on the level of systemic institutionalisation.

A third explanatory factor is fragmentation. The higher the number of parties, the more complex and unpredictable are party relations. Party systems where the 'effective' number of legislative parties is higher than four will be less institutionalised than more concentrated party systems.

Finally, we find that the more electorally successful anti-establishment parties are in a system, the less stable and predictable party systems will be. This follows Sartori’s traditional emphasis on the linkage between legislative fragmentation and ideological polarisation.

Party system closure is a significant phenomenon in the life of a party system. So what are the implications for democracy? Our analyses reveal two different, and to a certain extent contradictory, findings. These are that party system closure is good for the survival, but not necessarily for the quality of democracy.

party system closure is good for the survival, but not necessarily for the quality of democracy

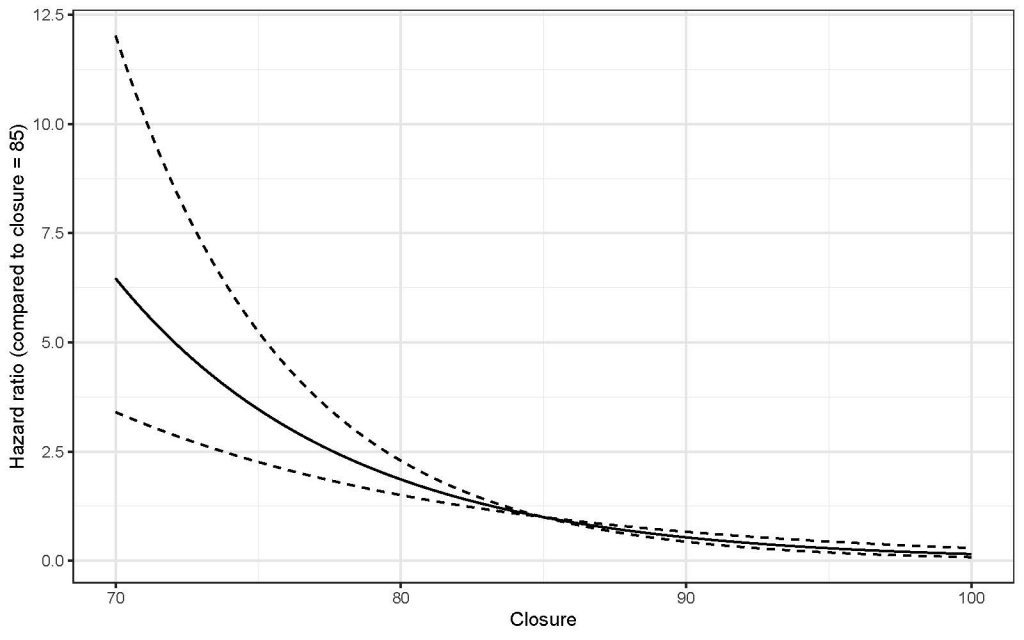

Indeed, and as follows from the figure below, if the level of party system closure drops below 70, democracy has a seven times higher probability of collapsing than in states with levels of closure near the European average of 86 or higher.

Our qualitative comparative analysis shows that we can consider closure a sufficient condition for democratic survival. In 171 years of European history, democracy collapsed in only one closed system: pre-WWI Greece. This is certainly encouraging news for the Armenians who recently held their second democratic parliamentary elections!

We can observe the relationship among the analysed factors not only across party systems but also across time in particular countries. In the book, we use process tracing to examine Germany, Spain and Hungary. Our aim is to determine how the different determinants of closure connect in a step-by-step temporal chain. The chain starts with democratic experience, is followed by party institutionalisation, then by party concentration. Finally comes low levels of polarisation before party system closure is achieved.

We also show that party system closure is not a panacea for all the ills of democracies. Under certain circumstances, it can even damage the quality of democracy.

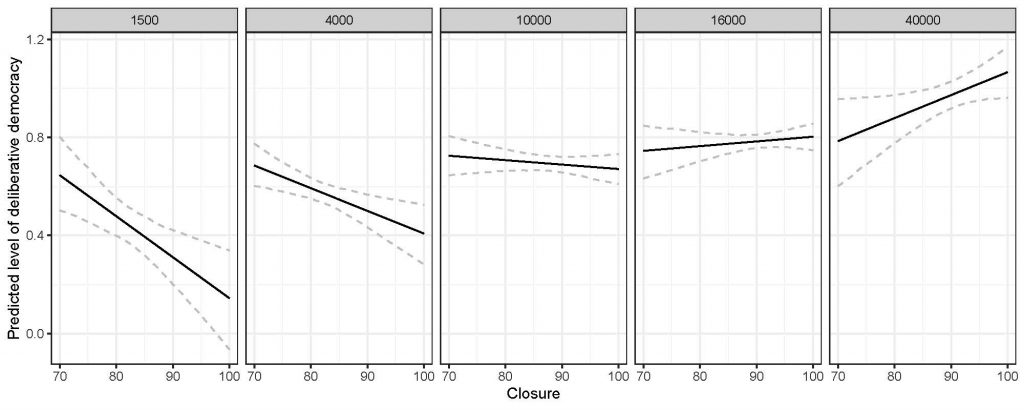

The figure below shows how, at low levels of economic development, party system closure has a rather negative effect on the level of deliberative democracy, as measured by V-Dem. In fact, and as shown in the book, this is true for all the dimensions of democracy. This explains why in poor countries with stable party systems like Albania, the quality of democracy is so low.

The message of history is pretty clear: build institutionalised party systems! Yet scholars and practitioners need to realise that the level of institutionalisation must be in synchrony with the social and political environment. What works in some settings may appear over-institutionalised in others.

In fact, closed party systems are likely to undermine the quality of democracy in less developed contexts.