Far-right parties are growing increasingly hostile towards LGBTQ rights. In the European Parliament elections, which take place from 6–9 June, such parties are expected to gain significant ground. Michal Grahn shows that non-straight voters might, through mobilisation, help keep far-right forces at bay

Research on LGBTQ behaviour shows that when LGBTQ rights are high on the political agenda, LGBTQ people are more likely than their heterosexual and cisgender peers to vote and participate in other forms of democratic action. We see this in North America as well as Europe. In closely fought elections with low turnout, a mobilised minority electorate can have a tangible impact on the electoral outcome. How minorities vote matters.

The growing success of populist radical-right forces is one of many factors mobilising LGBTQ voters. However, until recently, we did not know whether this factor alone was enough to motivate LGBTQ individuals to turn up at the ballot. In particular, we lacked knowledge about political participation rates among LGBTQ voters in liberal contexts in which their rights are well protected and where social attitudes towards them are generally positive.

My recent research in the European Journal of Political Research looks at voting patterns among Swedish lesbians, gays and bisexuals over time. I focus on elections in which LGBTQ group interests were politically salient, as well as those held long after the enactment of key LGBTQ rights.

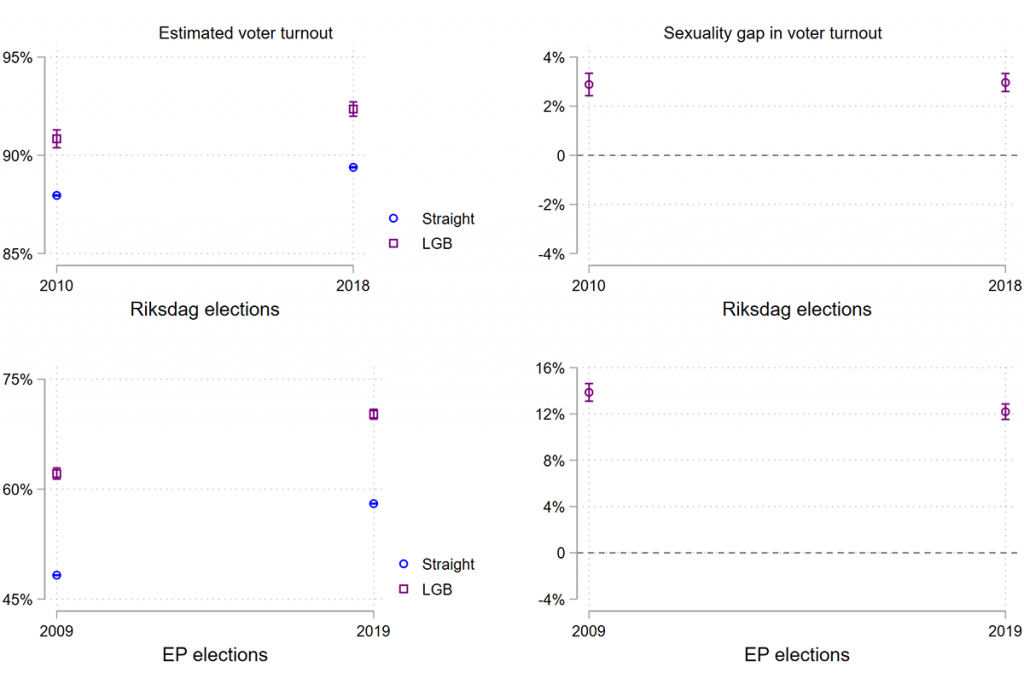

Leveraging comprehensive validated data on the Swedish population, I examine differences in voter turnout between non-straight voters and their heterosexual counterparts, across six elections between 1982 and 2019. The data shows a significant mobilisation of non-straight voters during key legislative changes affecting LGBTQ rights. More importantly, it shows that this mobilisation did not decrease, even after these rights had become well established and politically normalised.

In an electoral contest with only around 50% turnout, the LGBTQ community is a force to be reckoned with

Sweden's 2018 general election took place a full decade after the enactment of equal marriage. Even so, non-straight Swedes were still more than 3% more likely to turn out on polling day than their heterosexual counterparts. In the 2019 European Parliament (EP) elections, the turnout gap between non-straight and heterosexual individuals amounted to 12%. Clearly, the LGBTQ community is an electoral force to reckon with in a contest where only every other voter cast their vote.

We should set these figures in the context of Sweden, which is a leading global champion of LGBTQ rights. From 1995 to 2013, Sweden made significant advances in this field. These included legalising equal marriage, rights related to adoption, in-vitro insemination, and legal gender change.

When the benefits of political mobilisation are already won, do you still need to vote like your rights depended on it?

During this time, all major political parties in Sweden increased their support for LGBTQ rights. This coincided with growing social acceptance of sexual and gender minorities. Given this environment of strong rights protection and positive attitudes to LGBTQ people, one might expect the LGBTQ group identity to lose some of its political salience. This, in turn, would pave the way for a partial demobilisation of the LGBTQ electorate. After all, when the benefits of political mobilisation are already won, do you still need to vote like your rights depended on it?

The populist radical-right Sweden Democrats (SD) entered into national politics in 2010. Their rise could explain the continued mobilisation of the Swedish LGBTQ electorate. Initially, SD took an outwardly positive stance to LGBTQ rights, linking the protection of such rights to their broader anti-immigration agenda. This is an increasingly common electoral strategy, known as homonationalism. However, as support for the far right increased throughout the 2010s, SD adopted an increasingly critical stance. Once again, LGBTQ rights had become politicised.

For the LGBTQ people of Sweden, the rise of the SD has had real-world consequences. At the local level, SD-led municipalities have enacted policies harmful to the LGBTQ community. Nationally, SD has voiced strong opposition to expanding LGBTQ rights further, particularly rights aimed at trans individuals. The SD demonstrated this by their strong objection to the recent bill aimed at simplifying the legal gender change process. As SD's influence over national politics grows, it is reasonable to expect Swedish LGBTQ voters to mobilise in the forthcoming EP election.

The potential success of far-right forces in the elections to the EP represents a tangible threat to the wellbeing of LGBTQ communities in Europe. In countries where far-right parties hold power, LGBTQ rights have been rolled back. In Italy, for example, Giorgia Meloni's government recently moved to limit the rights of same-sex parents. It seems that LGBTQ rights protection – and generally positive attitudes to LGBTQ people – cannot reliably protect the community and their newly won rights from a conservative backlash.

LGBTQ rights protection – and generally positive attitudes to LGBTQ people – cannot reliably protect the community and their newly won rights from a conservative backlash

Will an organised LGBTQ electorate prevent far-right actors increasing their share of EP seats? Hardly. The current political winds appear to be favouring these political actors. We know that LGBTQ voters in Europe tend to support liberal, green and left-leaning political parties. A mobilised LGBTQ electorate can, therefore, make the continued cooperation of centrist powers within the EP a possibility. While the exact results of the EP election are yet unknown, one thing is certain. Europe’s LGBTQ community will vote as if their rights depended on it.