De-orientalising the scholarship on the Arab Gulf states is crucial, argues Dawud Ansari. Commentaries and datasets generalise them as ‘monarchies’, erasing vital differences between these countries. New terms are a starting point for transforming research on the wider region – an urgent objective given new crises and freshened global interest

1992’s Disney film Aladdin originally opened with lyrics about a land ‘where the caravan camels roam; where they cut off your ear, if they don’t like your face. It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home’ – lines so profoundly racist that even Disney decided to soften them (a bit). Aladdin’s world is nonsense ‘Agrabah’: white fetishism and French-American xenophobia, forged into the genericised imaginary of an Arab sultanate – as essayist Aditi Natasha deciphers. Sadly, the lens through which political science analyses real-world Arabia is often very similar.

Hager Ali opened this Autocracies with Adjectives series by asserting that political science structurally fails to treat autocracies with the same diligence it uses for democracies. She argues in particular that the discipline is even missing accurate data and terms to categorise autocracies adequately. The Arab Gulf countries are an excellent example.

Seminal datasets like Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions and Autocracies of the World yield Agrabahesque results. All Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states – Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – are nothing more than ‘monarchies’. Regionally, Jordan and Morocco share the same fate.

Seminal datasets categorise the Gulf states simply as 'monarchies', a label that is true but pointless

The label is true but pointless. First, ‘monarchy’ conveys little information beyond the existence of a lifelong head of state. This also applies to Sweden. Second, knowing that some country is a monarchy and not (also) a military dictatorship provides little added value. In many aspects, Jordan resembles Egypt more than Qatar. And hereditary rule is not exclusive to monarchies; consider Syria’s Hafez Al-Assad, who passed rulership on to his son Bashar Al-Assad.

‘Gulf monarchies’ educe Agrabah’s mythology – deserts, wealthy kings, conservative societies. Or, simply put, they are where ‘our oil’ comes from. The oversimplification is not just fertile soil for racism and fetishisation. It impedes empirical research and effective policymaking, whether that is Europe’s quest to secure gas and hydrogen or efforts to resolve security crises. The ‘monarchy’ label blinds researchers and policymakers to meaningful nuances.

Kuwait is a monarchy on paper but a pluralist semi-democracy in reality. Political, social, and commercial organisations run with broad autonomy, and Kuwait’s mostly-elected parliament – which provides legislation and can remove ministers – represents diverging perspectives.

The UAE is a federal system superimposed on autonomous emirates superimposed on tribal structures. Heredity and autocracy prevail in the individual emirates, but tribal power balances influence state politics. The federal government is an authoritarian system under the monarch of Abu Dhabi. Similar to the US, it features a separate judiciary. While certain fields belong under federal control, the emirates retain a large degree of autonomy, including mineral rights.

Oversimplification of the Gulf states' political systems impedes empirical research and effective policymaking, as well as being fertile soil for racism

Oman is a typical absolute monarchy with little separation of powers and a mostly inactive parliament. However, its diverse ethnic and tribal nature has fostered a unique system of broad representation.

Despite being a monarchy, Bahrain has legal provisions permitting and regulating political societies – basically parties. Powers are largely separated, and Bahrain’s parliament can amend the constitution and remove ministers. However, political dissidence is increasingly repressed; alongside Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Bahrain is becoming what Bakhytzhan Kurmanov labels an ‘information autocracy’.

Qatar, perhaps more than other Gulf countries, exemplifies a social class model differing from the Western conception of monarchies. Constituents receive vast resources and are granted (some) political participation. The modern-day peasant class, however, is the foreign-worker majority.

Saudi Arabia demonstrates how the ‘monarchy’ label also erases temporal gradients. It has always been the most autocratic Gulf country, but repression and power monopolisation have escalated under the current administration. The royal family constituted an informal system of checks and balances, but its dwindling power has put the country on track towards totalitarianism.

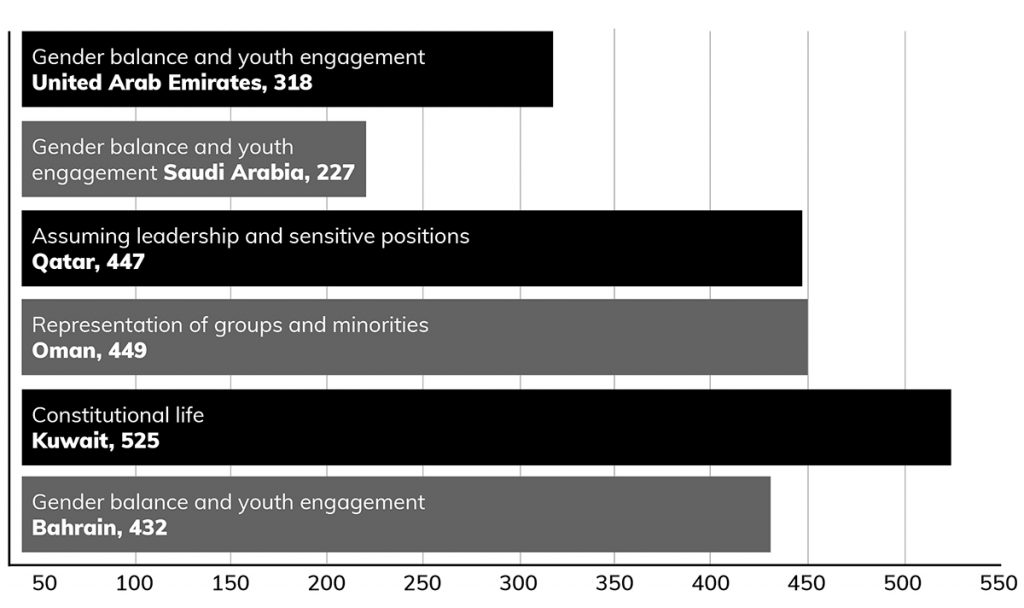

Such differences and gradients require a more nuanced terminology – or a dashboard. The Political Participation Index, an initiative by London-based think-tank Gulf House, is an excellent example of the latter. It assesses the six nations vis-à-vis ten dimensions of political participation, demonstrating substantial disparities (a relative standard deviation of 25%) between the ‘monarchies’.

No. ‘Monarchy’ is a simplification, but ‘theocracy’ is a sinister misrepresentation. It doubles down on denouncing ‘the other’. Similar to using ‘Sharia’ as a non-partisan punchline and modern-day spectre that preys on liberal values, the term ‘theocracies’ is used to portray real-world Agrabahs as backward dystopias and their populations as uncivilised subhumans.

In doing so, the term ignores the complex interrelation between religion, society, state, and history that is, at least somehow, reflected in all legislation globally. Equally, the term contains no information about political structures. It is antiscientific and not part of an honest taxonomy.

As Hager Ali’s inaugural text concludes, the way forward is not to recycle democratic terms and concepts to match autocratic counterparts. The implicit notion that autocracies are the liberal world’s Upside Down may well be the original fallacy that caused the shortcomings scrutinised in this series. The scholarship on non-democracies must become independent. It must not be squeezed into a single branch of political science, but evolve as an overarching research theme – with correspondingly increased resources.

Political scientists must finally let go of Agrabah to transform perspectives on the Gulf region and establish scholarship on the reality of autocracies

The orientalism inherent to (most) Western scholarship of the region obscures mechanisms, patterns, and nuances invaluable for knowledge and policy. Borrowing a term from philosopher Helen Verran, political science needs postcolonial moments: disruptions of Western-centric epistemic power relations towards a discursive construction of alternative knowledge systems.

Political scientists must finally let go of Agrabah to transform the field’s perspective on the region. This process requires the painful work of questioning textbook knowledge, its authors, and their research. De-orientalising the discipline starts with amplifying the voices of scholars from the region and those who seek to study the reality of autocracies instead of Disneyfied fantasies.

Maybe part of the problem is the "disciplinary" focus that somehow prefers to code, label and categorize the polity to make it explainable, intelligible and more often than not compatible with the existing social theory. In many instances existing disciplinary theory is way too positivistic and even simplistic to account even for a modicum of all the regional peculiarity. The researcher sets on the task of searching for empirical evidence for "theory" generated elsewhere and naively claiming to have a universal application, otherwise no theory and no science.

Another aspect of the issue is the comfort of fitting the regional context in these simple (Western?) "social scientific" terminology; monarchies, autocracies, rentier states, revisionist states, alliances, tribalism, Islamism, etc. In fact, social reality is way too complex, fluid and context dependent than we prefer to visualize it. This is the crux of the matter and a reminder for us that we have yet a long way to go. Scholarship of transdisciplinary area (regional) study have potential in bringing in the detail and knowledge of the specific geography, yet they need to accommodate theory in their work, something regional experts traditionally disregarded. All in all, a very hefty task in any case.