To understand today’s autocratic regimes, we should look at how they exploit social media, argues Bakhytzhan Kurmanov. In Kazakhstan, a referendum in the name of ‘open government’ is effectively a sham. What's more, it is a cover for autocratic practices of silencing dissent

Hager Ali has argued that we urgently need a deeper understanding of evolving authoritarian regimes. This is especially the case in relation to the impact of the social media revolution on these regimes – and how regimes exploit that revolution for their own ends.

Post-Soviet Central Asian states have, generally, imitated the democratic reforms promoted by the West, especially those associated with open government. To the external observer, this might look like a good thing. But there is more to this development than meets the eye – as we see in Kazakhstan.

Kazakhstan's first stage of reform in the tradition of promoting ‘open government’ began in 2019 with the election to the presidency of Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. His election had followed former President Nursultan Nazarbayev's sudden decision to step down.

Tokayev declared a wide-ranging liberalisation agenda based on creating a so-called 'Listening State', including a National Council of Public Trust. His apparent idea was to constrain state officials into 'listening' to citizens.

A second stage of liberalisation reforms began in the aftermath of riots in January 2022. The Kazakh government announced it would begin the transition towards a 'second republic' and the formation of 'New Kazakhstan'. The protests affected various regions of Kazakhstan and resulted in hundreds of deaths. The January riots exposed Kazakh citizens' intense dissatisfaction with the country's autocratic political system.

Responding to citizens’ demands for democratisation, Tokayev proposed 56 amendments to the constitution. These covered a wide range of issues, from reforming the constitutional court to changing the country's parliamentary system. They even called for removal the status of Kazakhstan's first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev.

Tokayev's reforms could prefigure the democratisation of Kazakhstan's hardline regime. But they are more likely to signal the emergence of an ‘information autocracy’

Tokayev called a national referendum on his professed vision of New Kazakhstan, for 5 June. But he failed open up his proposed changes to public discussion beforehand. Critics voiced serious concerns that citizens were unable vote on specific amendments. Rather, they must either accept all the proposed changes, or none at all.

Of course, it's possible Tokayev's proposed reforms could signal the democratisation of one of the region's hardline autocracies. But an alternative interpretation is that this is, in fact, an example of an emerging ‘information autocracy’.

Almost twenty years ago, as the internet and social media revolution gained momentum, political scientists predicted such technologies would ultimately crush autocracies. However, autocratic regimes evidently understood the power of social media and the internet. In the intervening years, they have harnessed these forces to develop a new form of regime: information autocracies.

Two decades ago, political scientists predicted social media would help crush autocracies. But that was before authoritarian regimes learned to harness online power for their own ends

Sergei Guriev and Daniel Treisman have recorded the emergence of so-called 'information autocrats' who use technology to control the information space. Such autocrats create government messaging that distorts reality and makes its citizens believe in the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes. Autocratic rulers realised social media and digital technologies could coordinate their supporters, disseminate propaganda, influence online discourse, and identify genuine threats to their regimes.

As a result, these new information autocracies impose controls over the internet and seek to dominate social media. Countries from Russia to China are now engaging online activists and pro-government internet trolls.

The Kazakh president uses Twitter to react to citizens' requests, but the consequences for political activists of using social media remain unchanged. In 2021, two activists were arrested in the Almaty region for criticising the government on social media and calling for citizen protests. A number of political activists were jailed or fined for protesting in Almaty during April 2022.

Kazakhstan's ranking in the Freedom on the Net index is low, and freedom of expression is obstructed. Moreover, in January, the Kazakh government temporarily shut down the internet in an attempt to clamp down on protesters.

In classic autocratic tradition, no public campaign against the 5 June referendum proposals has materialised. More striking is the fact that Kazakh authorities were mobilising resources to persuade citizens to vote. As in information autocracies, the Kazakh regime is exploiting all digital technologies and resources to promote its narrative.

As in information autocracies, the Kazakh regime is exploiting all digital technologies and resources to promote its narrative

Secretary of State Yerlan Karin discussed the urgency of the referendum during a recent congress of Kazakhstani political scientists in Almaty. On Instagram, bloggers and activists mobilised to organise meetings with staff of numerous state and quasi-state organisations, from kindergartens to universities, to promote the proposed changes to the Kazakh constitution. Even TikTok users urged citizens to go to the polls and build a 'New Kazakhstan' rather than leave the country.

All of which is clear evidence of Kazakh authorities' realisation of the importance of controlling and influencing citizens on social media.

The constitutional referendum took place on 5 June without significant protests, and citizens went to the pools as expected. Preliminary results indicate that 68% of all eligible Kazakh citizens voted. Unsurprisingly, 77% expressed their support for the 'New Kazakhstan' vision at the referendum, while 18% voted against the changes to the Constitution.

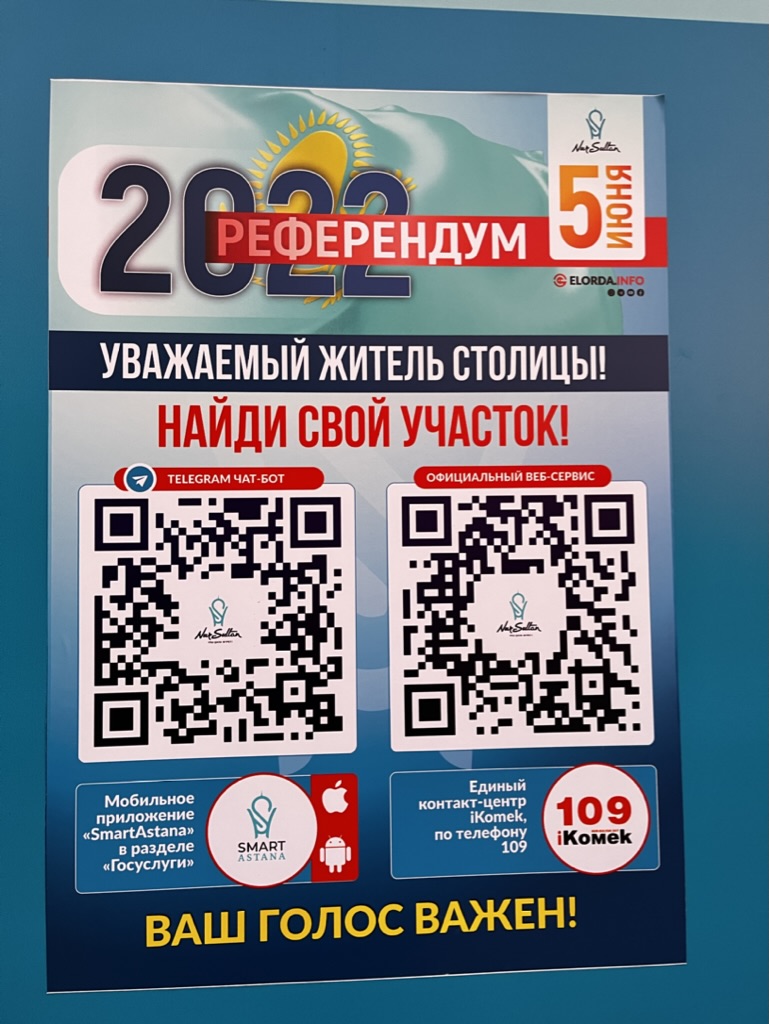

A poster calls for citizens of Nur-Sultan city to find their polling stations and vote

Optimists may interpret the 'Listening State' and the agenda of political reforms in Kazakhstan as the democratisation of a hybrid regime. Yet, a more accurate interpretation is one that views the reforms and constitutional referendum as stepping stones toward a form of information autocracy.

The massive digital campaign and the co-option of activists on social media in support of the referendum reveal how the Kazakh regime is being transformed into an information autocracy. It is one which seeks, above all, legitimisation and the construction of a good image, both at home and abroad.