Fixing numbers is not enough. In their second-generation design for inclusive democracy, Karen Celis and Sarah Childs refashion representation processes to incentivise elected representatives to care more for diverse citizens. The designed-for effects? Experiencing better representation ‘in the round’; the most marginalised people feeling recognised by and connected with democratic politics

This series has called for greater focus on individual conceptions of democracy. We answer this call with a focus on 'inclusive democracy'. How can parliaments and representation contribute to inclusive and strong democracies?

Two decades ago, the late Iris Marion Young advocated for group representation:

Whenever the group’s history and social situation provides a particular perspective on the issue, when the interests of its members are specifically affected, and when its perceptions and interests are not likely to receive expression without that representation.

iris marion young, Inclusion and democracy, 2002

Young's justification still stands. That said, first-generation designs to redress the poor political representation of excluded and underrepresented groups are in need of serious updating. We therefore set ourselves the task of drafting a second-generation design.

1990s presence theories underpin first-generation designs. These theories proposed that the solution to women’s underrepresentation was to repopulate parliaments with women representatives, using gender quotas as their handmaidens. For other groups, such as ethnic minorities, reserved seats were key.

These new elected representatives would embody political equality. The proponents of gender quotas also hoped that women and minority representatives would better represent their respective groups’ interests. Even so, they were ‘added’ to existing parliaments’ absent institutional interventions that could guarantee the representation of group interests.

Despite improvement in the diversity of elected representatives, most parliaments have yet to achieve numerical equality. And even where there is greater diversity, such presence does not necessarily engender greater attention to their concerns. Today, questions of within-group inequality have become more pressing still. For example, increases in elite women representatives beg serious questions about the inclusivity of formal politics when marginalised and minoritised women are excluded and/or marginalised.

Even when parliaments do enjoy diverse elected representatives, it does not necessarily engender greater attention to minority groups' concerns

Representational deficits remain in important ways beyond numbers, too. We frequently define political agendas and party competition by the traditional interests of dominant groups, with political institutions insufficiently responsive and accountable to diverse electorates. We thus marginalise diverse experiences and voices, missing and/or misrepresented in political debate.

Our new design, presented in our book Feminist Democratic Representation (OUP, 2020), makes two key updates.

First, rather than limiting the design intervention to increasing the diversity of representatives, we attend to the wider poverty of political representation. Inclusive representation requires presence but also richer political conversations, broader political agendas, meaningful accountability, and feelings of affinity, connection, and recognition.

Second, our design ensures the advocacy, listening, deliberation, and responsiveness to multiple experiences, needs, and interests, not least the most marginalised.

To bring our design to life, we introduce a new set of political actors: affected representatives. These actors represent the views and needs of citizens who are affected differently by a political issue or problem. Designated representatives are ‘equal of sorts’ with elected representatives. They ensure that discussions of a group’s issue include the factual and affective ‘knowledge’ of all relevant within-groups. Affected representatives are chosen by those they go on to represent, precisely because they share an understanding of what the problem is, feels like, and how it might be addressed.

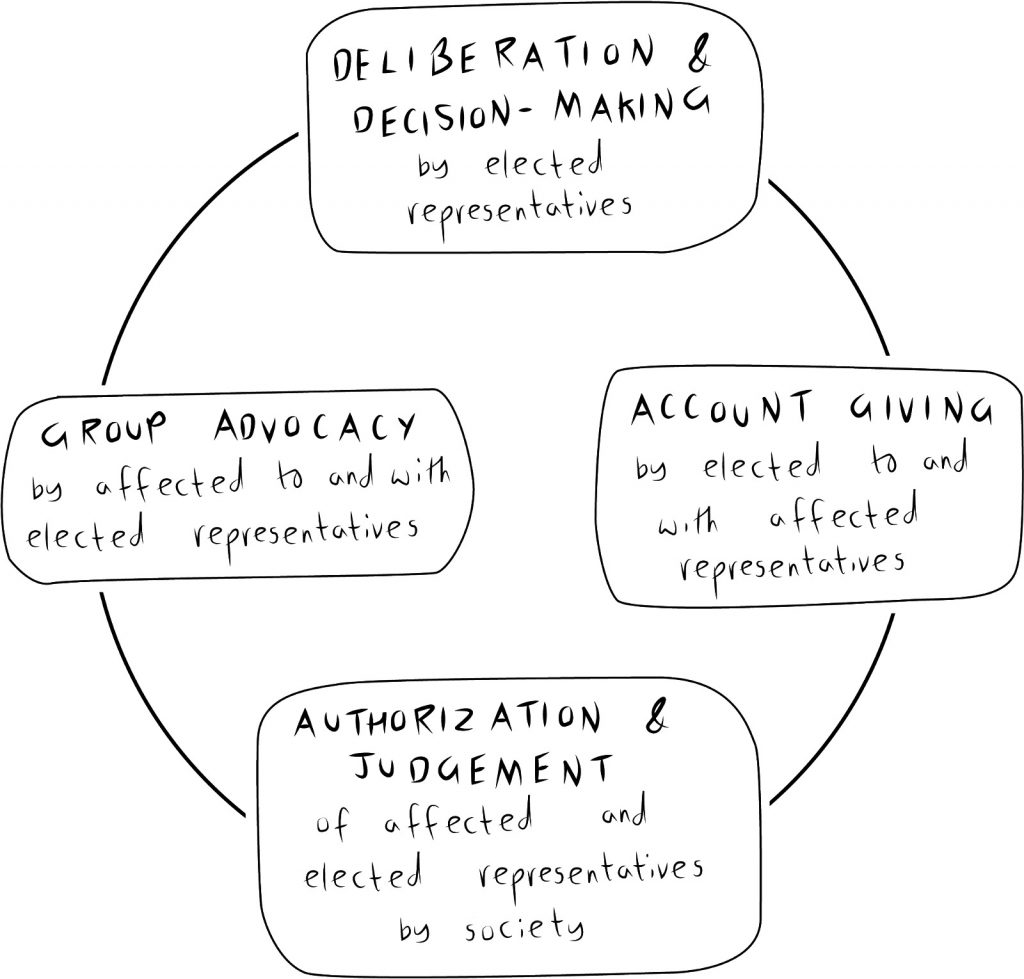

Affected representatives engage in two formal parliamentary moments. In group advocacy – the input phase – the differently affected speak before elected representatives. Account giving – the output phase – is where elected representatives explain and justify the content, course, and conclusions of their deliberations to the affected representatives, who judge the quality of representation. These twin augmentations create and embed conducive contexts to make the deliberation and decisions by elected representatives – the throughput stage – better meet diverse representational interests, and thus produce just and fair outcomes.

It is the transformation in the attitudes and behaviour of elected representatives that we design for. Elected representatives are enabled and motivated to learn from groups usually considered hard to reach (read: easy to ignore). Politicians are ‘in the room’ with affected representatives and ‘exposed to’ the latter’s passionate as well as factual claims.

Elected representatives thus gain incentives to care more for those groups that they usually experience as ‘other’; politicians’ thoughts, feelings, and policy and legislative intentions may well recalibrate. Parliaments become public sites; what goes on inside is highly visible. Elected representatives will be judged within and beyond the institution. Turning one’s back on affected representatives invites reputational risks, individual and institutional.

With our design in place, formal political representation becomes an experience of inclusion, responsiveness, and egalitarianism. A wide variety of citizens see ‘people like them’, face-to-face with elected representatives. Citizens formerly excluded partake in the ‘public speech for the nation’, via their affected representatives who give them voice. The greater emphasis on accountability transforms hearing into listening and, in turn, into responsiveness.

In our design, face-to-face with elected representatives, a wide variety of citizens see 'people like them'

There is, too, a change in language and tone. Affected representatives use their own speech styles, and elected representatives are therefore motivated to address the former in ways that connect, not least to increase their persuasiveness.

Parliaments will have now become amenable sites for the redress of political problems for those who previously experienced politics as exclusion: ‘not about, nor for them’. The represented thus feel recognised, with legitimate political experiences, needs, and interests. They gain greater affinity and connection with the actors and institutions of representative democracy, and this should, over time, revitalise political participation. Citizens, civil society, and electoral politics should become more strongly linked together.

What we suggest is hugely demanding of political institutions. To generate the desired effects, our design should be part of the routine work of a parliament. It will inevitably slow down politics. Yet, we have confidence that our second-generation design has appeal.

Making our political institutions properly inclusive might just be one, very good, way of bolstering what at present look like rather shaky political institutions. Parliaments properly inclusive of a society’s diverse groups make for stronger democracies.

No.91 in a Loop thread on the science of democracy. Look out for the 🦋 to read more in our series