‘Securitising’ an alleged external threat can be a convenient tool for political leaders to justify extreme measures and policies. Dionysios Stivas looks at the case of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s handling of asylum seekers in 2015

To securitise is to represent political issues like migration and climate change as security-relevant, and to treat them as such. In the hands of political tricksters, securitisation can become a malicious tool.

In 2015, Viktor Orbán arguably used securitisation in an arbitrary way to deal with rising numbers of asylum seekers at the Hungarian border. Orbán alleged that the asylum seekers were terrorists, criminals and threats to the cultural, economic, and societal security not just of Hungary, but the whole of Europe. Orbán’s securitising narrative laid the groundwork for his government's adoption of extraordinary migration-restrictive measures.

Was Orbán accurate to assert that the asylum seekers threatened Hungary’s security? Retrospectively, it is clear that Orbán’s allegations were unsubstantiated and exaggerated. The Hungarian Prime Minister misrepresented the refugee crisis. By so doing, he deceived the Hungarian public into accepting his securitising narrative and measures.

Yet even before Orbán’s securitising moves, a large proportion of the Hungarian public considered immigrants and asylum seekers security threats. This suggests that it was not so much a case of the Hungarian leader misleading the Hungarian public. Rather, it was that his rhetoric on immigration resonated with the Hungarian populace.

During the refugee crisis, Orbán associated immigration with terrorism. He presented asylum seekers as ‘economic migrants’, and argued that they ‘bring no benefits but only danger to Europe’. Following the deadly terrorist attacks of November 2015 in Paris, Orbán argued that ‘there is a correlation between immigration and terrorism’. Moreover, he warned that

mass migration is threatening the security of Europeans because it brings with it an exponentially increased threat of terrorism

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, 2015

That same year, Orbán and his party, Fidesz, organised a National Consultation on immigration. It contained leading questions presupposing that immigrants generated terrorism, along with economic, societal, and cultural insecurity.

Yet, despite his securitisation rhetoric, a closer look at numbers and intentions indicates Orbán doubly misrepresented the alleged threat. Firstly, Hungary was not the asylum seekers' final destination. Secondly, between 2014 and 2016, Hungary experienced a decline in the number of immigrants entering the country.

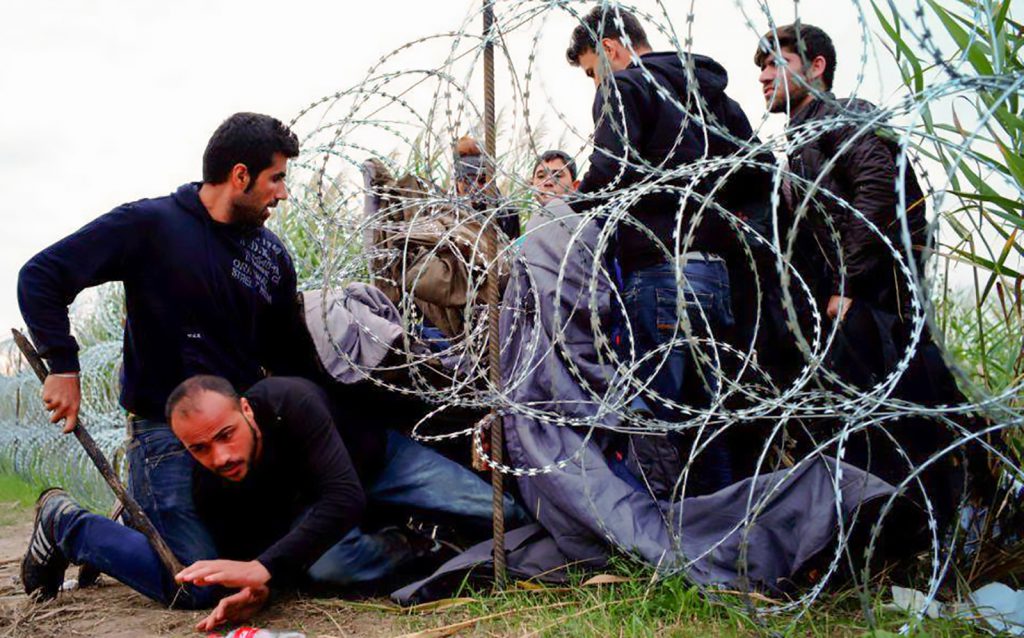

Acting on the securitisation rhetoric, in June 2015, the Hungarian government took drastic action to curb the flow of immigration. It announced that a 175km long, 4m high razor-wire fence would be erected across its borders with Serbia. Similar barriers were later erected at the Hungarian borders with Romania and Croatia. The total cost of the fences reached €800 million.

In terms of migration-restrictive legislation, in 2015 the Hungarian Parliament amended the Hungarian Criminal Code, the Asylum Act, and the Criminal Procedure Act. The amendments of the Criminal Code made ‘illegal border crossing’ a criminal offence, punishable with three years’ imprisonment. Causing damage to the newly constructed border fence could result in five years' imprisonment.

The new Asylum Act put in place provisions against a ‘mass migration crisis’. Thus, it empowered the police and army to intervene in asylum procedures.

The new Asylum Act empowered the police and army to intervene in asylum procedures

Orbán introduced legislation altering the rules regarding the list of safe ‘third’ countries. What's more, he curtailed deadlines for authorities to decide an asylum-seeker’s case, and for the applicant to challenge a negative decision. He also denied the suspensive effect of any appeal in most of the accelerated procedures, took away all integration assistance from recognised refugees or beneficiaries of subsidiary protection, and introduced a compulsory review of the status of refugees.

Most of these physical and legal barriers established by Orbán’s governing party contravened the basic provisions of international and European law.

These measures, and their accompanying securitising rhetoric, were generally well received by the Hungarian public. In 2015, while hundreds of thousands of immigrants attempted to trespass across Europe’s south-eastern borders, 82% of Hungarians admitted having negative feelings about immigrants from outside the EU. A Tent Tracker survey revealed that 70% of Hungarians thought that if their country accepted more refugees, it would jeopardise their security. 82% considered refugees threats to their economic wellbeing, and 76% viewed asylum seekers as generators of domestic terrorism.

In 2015, 70% of Hungarians thought that if their country accepted more refugees, it would jeopardise their security

The ‘waves’ of refugees were also blamed for the rise of criminality by almost one in two Hungarians. In 2017, almost eight out of ten (78%) were antipathetic towards immigrants from outside the EU. In August 2017, 74% were concerned that refugees would increase the risk of terrorism. 66% felt that the more refugees Hungary accepted, the greater the risk to Hungarians’ security.

Orbán, and large proportions of his electorate, shared xenophobic views about immigrants. In this context, Orbán encountered no domestic resistance to the implementation and enforcement of anti-immigration, and possibly unlawful, securitising measures.

Securitisation can turn into a dangerous instrument even in the hands of democratically elected leaders. Orbán, although criticised for turning Hungary into an illiberal democracy, is a democratically elected leader.

Building on the xenophobic tendencies of his electorate, Orbán framed asylum seekers as terrorists and criminals. The Hungarian people's negativity towards immigrants from outside the European Union bolstered the effectiveness of Orbán’s securitisation narrative.

Could other democratically elected leaders misrepresent a threat and securitise it, as Orbán did with the refugee crisis? It largely depends on popular sentiment; it is the general public that ultimately determines the success of securitising an issue such as migration. One thing is certain: political leaders can exploit an alleged external threat by securitising it and manipulating public opinion to serve leaders’ own political goals.