Hungary’s government recast Budapest Pride as a danger to children and national security, then banned the 2025 march. Varvara Prodai’s data show that the 'security threat' framing spiked in Hungarian, while English-language messaging remained legalistic, revealing a two-track playbook that weakens minority rights and narrows civic space

In March 2025, Hungary's parliament passed a law that allows police to ban LGBTQ events, fine attendees, and use facial recognition to identify them. The government's argument is that child protection outweighs assembly rights. Its move paved the way for police to prohibit Budapest Pride, drawing swift criticism from EU partners and rights groups.

Officials from the ruling party Fidesz had been priming the public for months. They added 'Pride' to their list of 'security' menaces facing Hungary that also includes 'Brussels', 'migration', and 'war'. On the Fidesz Facebook page, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán sneered, 'What the heck would I have been doing there [at Pride]?' and claimed 'the country [had] already decided' against Pride by re-electing him in Hungary's 2022 parliamentary election. Chief of Staff Gergely Gulyás insisted the government was 'defending children, not acting against sexual minorities'. He also warned that any Pride activities outside the child-protection law would be deemed a 'provocation'.

Hungary's new law lets police ban LGBTQ events such as Budapest Pride under the guise of 'child protection'. The law has drawn fierce criticism from EU partners and human rights groups

In another post, the government's message hardened: 'Brussels decides, a puppet government executes… there’s gender, migration, and we’re neck-deep in war'. Fidesz’s European Parliament delegation added: 'There’s no place for LGBTQ propaganda in child protection'. This rhetoric mirrors wider illiberal trends documented by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation.

At home in Hungary, Pride became an existential threat and a supposed foreign plot. On the eve of the march, Orbán claimed 'Brussels issued an order that there must be a Pride' and called the event 'repulsive', a charge he tied to sovereignty and public order.

In Hungary, Orbán positioned Pride as an existential threat and a foreign plot. Outside of Hungary, however, he used legal rhetoric, urging Brussels to refrain from interfering in the laws of member states

Abroad, the tone shifted. When EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen urged Hungary to allow the march, Orbán’s English response pushed for Brussels to 'refrain from interfering in the law-enforcement affairs of member states'. He stressed Hungary’s 'civilised' approach, while reaffirming that child protection supersedes other rights. Orbán’s legalistic gloss stood in stark contrast to his domestic messaging.

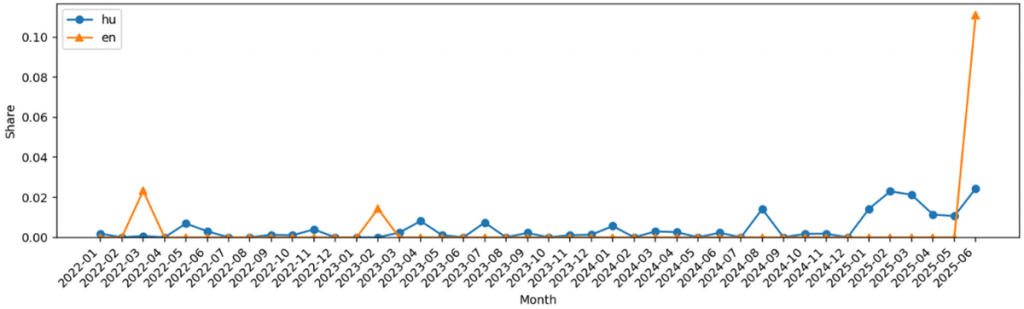

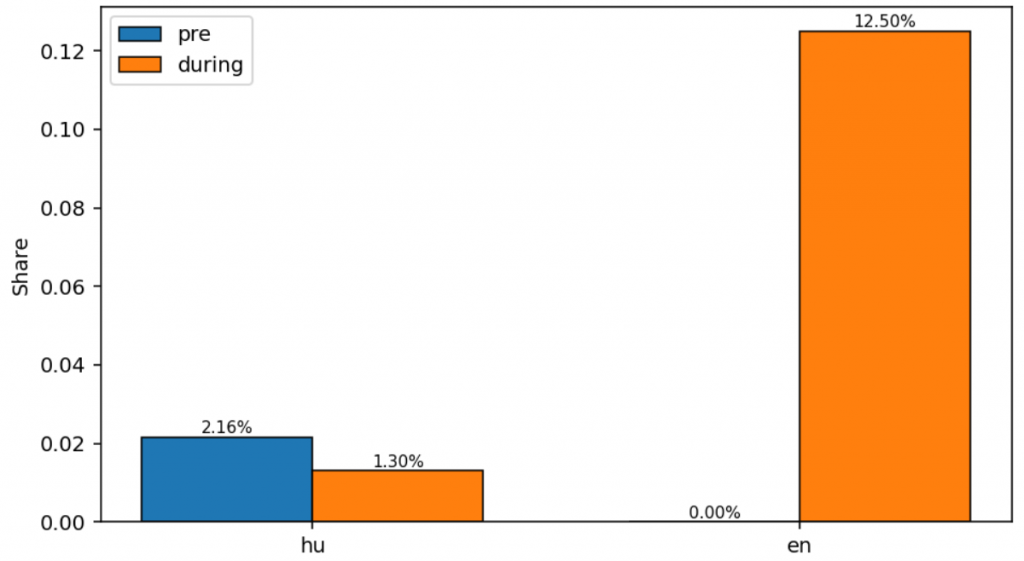

Indeed, the data reveals his two-faced communication strategy. Analysis of 2025 Facebook posts by Hungarian government officials and ruling-party politicians, especially those in Hungarian language, reveals a sharp spike in content linking LGBTQ Pride to security threats, or 'protecting children'.

During the event period surrounding the ban, the share of Hungarian posts carrying this frame jumped from 1.16% pre-event (4/345) to 3.55% during (15/422) — a three-fold increase. Per Pride-related posting, the rate rose from 133 to 188 hits per 100 Pride mentions.

In English, there were no such posts during the period (0/2) after a single pre-event instance (1/7). The base is small, but the direction is unambiguous: the hardline framing targeted domestic audiences.

Just before Pride, only 1.16% (4/345) of Hungarian-language posts framed Pride as a security issue. During/after the ban period, that jumped to 3.55% (15/422). In English, there were zero such posts during the ban (and only one beforehand).

It wasn’t just volume. The register changed. Party pages increasingly associated Pride with war and migration, and suggested supporters were merely parroting foreign scripts. The legislative track moved in parallel: measures elevated child-protection claims above assembly rights and widened surveillance powers. The sequence is textbook securitisation — alarm, amplification, legal entrenchment — and it maps one-to-one onto the quantitative surge.

Fidesz's strategy mobilised its supporter base, branded opponents and Budapest’s city hall as pro-Brussels, and distracted from genuine governance concerns. A local Facebook page of the right-wing nationalist party Jobbik even complained that while the country fixated on Pride, crime was surging in rural towns. Similarly, Jobbik MP Róbert Dudás argued that policing capacity had collapsed and violent crime had risen steadily since 2022. This fits a broader authoritarian pattern: repackage a cultural dispute as a security emergency to justify extraordinary measures.

The costs to democracy are plain. A blanket Pride ban violates the freedom of assembly, and chills dissent far beyond LGBTQ communities. Treating a peaceful march as a public-order threat normalises facial-recognition policing and legal intimidation, tools easily turned on any protest. EU partners have sounded the alarm as Hungary narrows civic space under the banners of 'child welfare' and 'security'.

Fidesz's strategy to repackage a cultural dispute as a security emergency failed politically, as tens of thousands took to the streets for Budapest Pride

Politically, the gambit misfired. Tens of thousands defied the ban, turning Budapest’s Pride into a vast anti-government rally — one of the largest of the Orbán era. The government warned of 'legal consequences', but the optics told a different story: repression bred mobilisation.

Hungary’s leaders tried to turn a celebration of equality into a security crisis. Instead, they got a civic awakening. The lesson travels: whenever governments recast minority rights as threats, democracy becomes collateral. Citizens, at home and abroad, should recognise the script and refuse to play their assigned roles.