The war in Ukraine has focused attention on public attitudes to arms exports. New research by Lukas Rudolph, Markus Freitag, and Paul Thurner finds that in France and Germany, while a small minority is in principled opposition, a large majority makes nuanced trade-offs when articulating their positions on the issue of arms exports

Since Russia began its war of aggression on Ukraine, arms transfers have become the subject of intense public debate. In many democratic countries, citizens take strong positions on whether their countries should export arms and, if so, precisely which arms their country should transfer.

The German debate is emblematic in this respect. Citizens fundamentally opposed to arms exports have, before and after the war in Ukraine, taken to the streets. But the majority of Germans changed their opinion on arms transfers to Ukraine when Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, after which they were in favour of transfers of even heavy weaponry.

Which arms transfers do citizens see as legitimate or acceptable? Does this depend on context?

However, we know barely anything about the underlying structure of citizens’ attitudes. Which arms transfers do citizens see as legitimate or acceptable? Does this depend on context?

For our recent article in EJPR, we conducted large-scale survey experiments on two top exporting nations, France and Germany, in 2021. Our results reveal evidence of the fundamental trade-offs that occur when citizens consider the many conflicting objectives and consequences associated with arms transfers.

We tackled the complexity of public discourse via a conjoint experiment in which we directly map citizens’ deliberation processes. Respondents have to weigh several – usually conflicting – goals simultaneously, to reach an assessment of prototypical arms trades.

This original design distinguishes our experiment from conventional surveys that ask multiple separate questions. Of course, under real-world conditions, an individual would not be able to consider separate aspects in isolation. Rather, each aspect would influence the other. Additionally, as our experiment is embedded in a quota-representative survey, it allows us to make statements about entire societies.

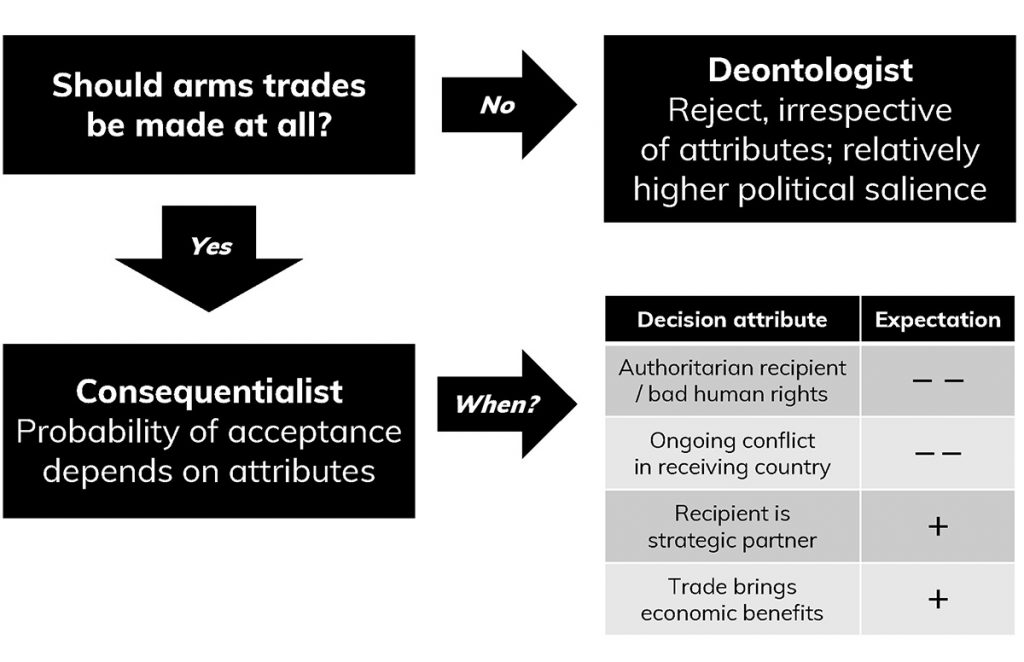

Theoretically, we propose dividing citizens into two groups, as below. On one hand, there are those with deontologist preferences, who reject any arms transfers independent of context conditions. This group, for example, includes people with firm pacifist convictions. On the other, there are people who consider the nuanced pros and cons that any arms transfer might involve regarding the local job market, strategic country objectives, or normative aspects about the situation in the receiving country.

The trade-offs are quite fundamental. For example, citizens have to weigh human rights abuses in the recipient country against potential jobs at home or against trade advantages. Or they may have to consider that this country is an allied partner in the fight against terrorism.

There are many such trade-offs, but the existing literature, predominantly from the field of political economy, has investigated only how governments take these pros and cons into account. This literature explains decision-making mainly on instrumental grounds, i.e., focusing on economic and geo-strategic aspects of a trade. This provides us with an abstract theoretical template that we can compare to citizens’ decision making.

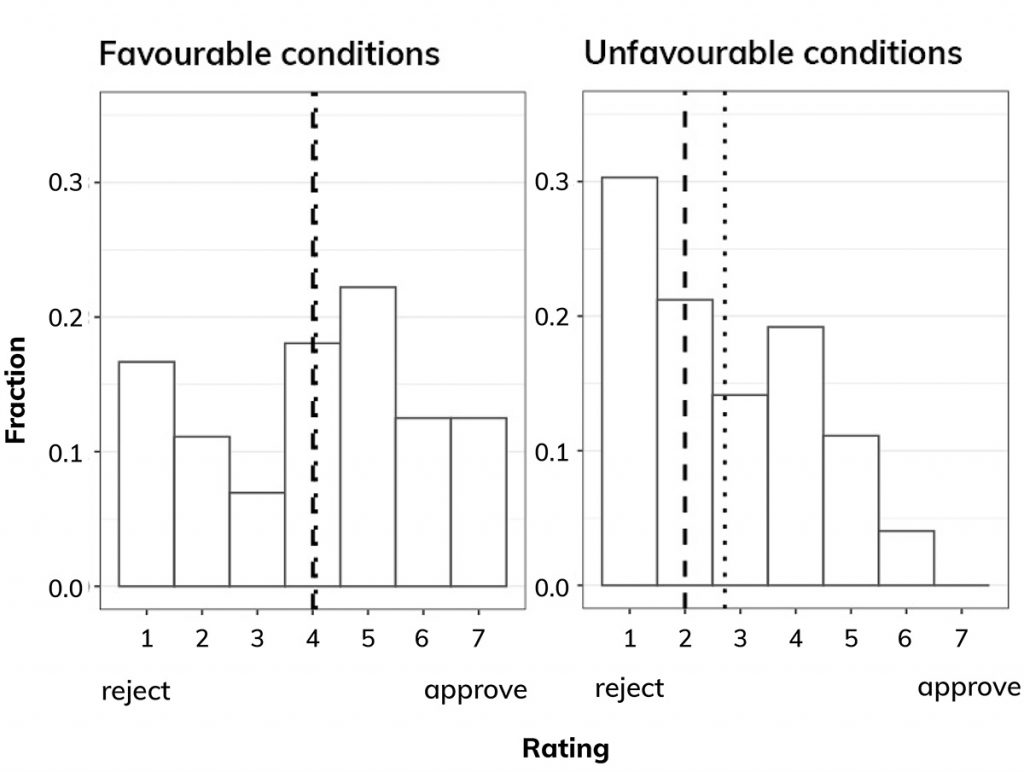

Empirically, we show that this template, which might work for governments, does not match citizens’ calculus. The graphs below present citizens' preferences to reject or approve arms trades, comparing over two experimental scenarios: on the left for arms trades highly favourable with respect to economic, strategic and normative implications of trades; on the right for those unfavourable on these dimensions. Even with highly favourable conditions, around a sixth of respondents is in fundamental opposition. But a majority is in tentative support. However, when context conditions become unfavourable, the share of rejections increases markedly.

Generally, a relevant subgroup of respondents voiced principled opposition to any arms trade. But a majority based its approval on considerations of strategic, economic, and, most important, normative consequences. What type of regime does the arms trade benefit? Does the arms trade uphold human rights? Is there conflict, and, if yes, is the country rightfully defending itself?

In our experiment, tentative approval can only be achieved when a democratic (and, at best, peaceful) context comes together with high economic and strategic benefits

If we bring our data to bear on specific countries, we predict clear overall rejection of arms trades with autocratic regimes, conflict situations, or human-rights violating contexts. These could include, for example, Saudi Arabia or Azerbaijan. Even very high economic benefits for the home country would not persuade an individual to reverse their rejection.

An individual will offer tentative approval only when a democratic (and, at best, peaceful) context goes hand-in-hand with high economic and strategic benefits, such as arms exports to EU countries. Our results show that the specific circumstances of an arms transfer can induce substantial swings in public support. This corresponds closely with what we see in real-world public opinion polls on arms transfer before and after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Comparing the contexts of France and Germany, citizens of both countries use the same fundamental calculus. Still, principled opposition is greater in Germany than in France, though not as high as current public debates might suggest. This indicates that many citizens who currently oppose arms transfers to Ukraine might do so for the strategic or economic benefits opposition might bring.

We still don't know the extent to which attitudes toward arms transfers can be structured along established ideological lines of political competition and affiliation with particular parties.

Arms transfers to conflict regions see much lower approval rates, but scenarios of 'just war' alleviate this penalty

In Germany, for example, the Green Party takes a much more proactive role than the Social Democratic Party in supporting Ukraine. We attribute this to the Greens' stronger advocacy for the Responsibility to Protect principle. This echoes our results: arms transfers to conflict regions attract much lower approval rates, but scenarios of 'just war' alleviate this penalty.

Our survey took place about a year before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and it maps the sentiment on arms exports in two countries that deal with arms exports in very different ways. This is an advantage, because it allows us to analyse reactions to stimuli in somewhat polarised societies. It also allows us to continue our survey and measure current preferences. Going forward, we will have the tools to accurately assess whether ongoing public debates influence citizens' fundamental trade-offs.