Herman Melville’s 'ruthless democracy' is a creative performance, argues Jennifer Greiman, which guides Melville’s experimental prose and poetry. This sought to reimagine democratic relations, possibilities, and ways of being as matters for aesthetic thought and work – with strong implications for political theory

As he was finalising Moby-Dick in the summer of 1851, Herman Melville wrote a long and somewhat rambling letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne. In it, he articulated a principle that he called 'my ruthless democracy'. This was his name for a commitment to unconditional equality that 'boldly declares that a thief in jail is as honorable a personage as Gen. George Washington'. Like others in this series, Melville took democracy seriously as a problem of philosophical, political, and aesthetic thought. And this thinking took place across a career that spanned five decades, nine novels, four volumes of poetry, and more than a dozen short stories.

Ruthless democracy is a commitment to the fundamental equality of human (and nonhuman) life that demands a receptivity to perpetual change

'Ruthless' is not a descriptor normally attached to democracy. Unlike familiar modifiers – constitutional, representative, direct – it does not simply describe a stable and recognisable form that the rule of a people might take. Instead, 'ruthless democracy' describes an egalitarian principle that is pursued without sentimental attachment to the permanence of any particular form. It is a commitment to the fundamental equality of human (and nonhuman) life that demands a receptivity to perpetual change.

Conceiving of democracy as a commitment to both equality and transformation, Melville further shows across his writing that democracy has colours, shapes, textures, and movements. Founded in both verdant nature and painted artifice, it is green. Authorised by the popular sovereign it rules, it is round. And rooted in transience and recurrence, it is without permanent ground.

Direct, representational, constitutional, liberal. Democracy demands modification to signal all of the qualitative and sensible distinctions that characterise its many forms.

Even radical democracy requires such modification. It is often defined as a transient force that opposes fixed foundations in a particular people or form of rule. Thinkers such as Sheldon Wolin, Jacques Derrida, Claude Lefort, and Jacques Rancière have variously theorised it as fugitive, to come, empty, and groundless. Radical democracy, therefore, is the compound name for the thesis that, at root, democracy is always becoming something else.

Now, contemporary democratic theorists increasingly consider the aesthetic dimensions of collective politics. But the precise relationship of aesthetics to democracy remains unclear. Does democracy have distinct aesthetic qualities? Or is democracy itself as essentially aesthetic a concept as it is a political and philosophical one?

Melville’s body of work argues for the latter. If democracy is radical and fugitive, if it is ruthless and unconditional, then it is aesthetic. But this does not mean that it is mere fiction. Instead, ruthless democracy consists of the creative forces that materialise, however briefly, its distinct colours, shapes, textures, and possibilities.

Ruthless democracy lies at the centre of Melville’s work. It is the principle that connects his accounts of shipboard mutinies and Polynesian communities, purposeful whales and baffling Wall Street scriveners. It lies in his memorable depictions of collective action, passive resistance, and revolutionary insurrection. Beyond that, it also lies in those scenes of tyranny, violence, and counter-insurgency that repeatedly send democratic actions and actors into retreat.

Where Melville's plots emphasise the fragility and transience of democracy, his aesthetics of figuration, analogy, and abstraction show how democracy’s power persists in its capacity to transform itself

Melville’s work often traces the defeat of collective formations and democratic movements on the level of plotted narrative. But he nevertheless holds open democratic possibilities through non-narrative aesthetic registers. Where his plots emphasise the fragility and transience of democracy, his aesthetics of figuration, analogy, and abstraction show how democracy’s power persists in its capacity to transform itself.

One of the most potent examples of figuration in Melville’s work can be found in his frequent use of circular figures. Through these, he imagines formations of democratic agency across several of his nautical novels from the 1840s and 1850s.

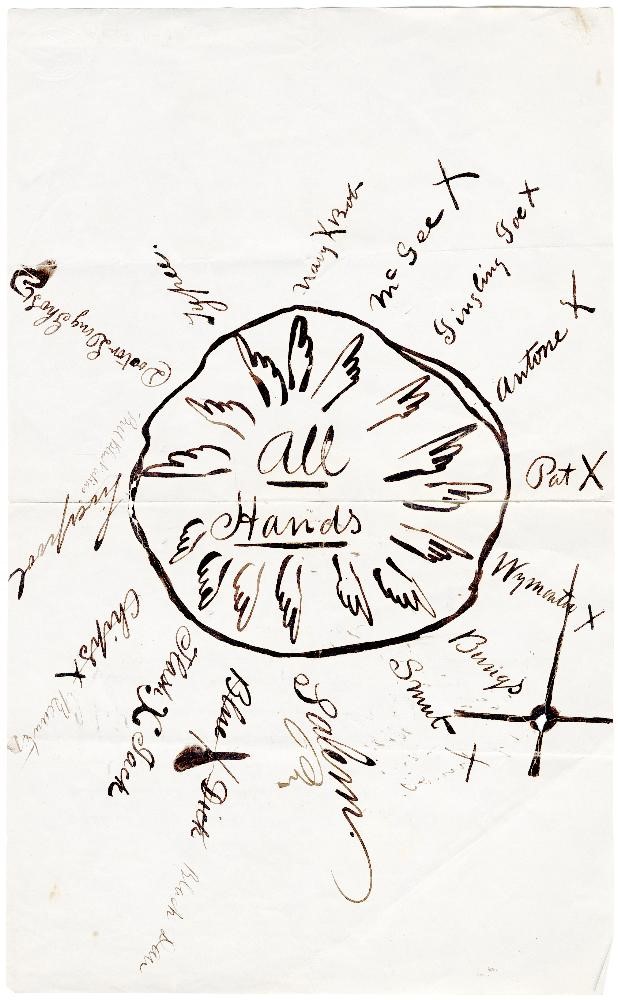

The circle first appears as a powerfully democratic figure in Melville's 1847 novel, Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas. The sailors on a decrepit whaling ship instigate a mutiny by drawing up a 'round robin'. This is derived from accounts of an eighteenth-century pirate insurrection, and Melville both narrates and reproduces it on the page. The round robin comprises a circle, with several crudely drawn hands pointing outward to a series of names written as rays along the circumference.

The round robin serves as a group signature to a petition for the sailors’ right to free themselves from tyrannical treatment. No name has preeminence. The signature constitutes its subject as both collective and leaderless. That subject does not presuppose itself or its authority because it arises through the very act of collective representation which is at once aesthetic and political.

On the level of plot, the round robin has a limited effect. It gets the sailors off the ship and lands them in a Tahitian prison. But on the level of figuration, it travels through Melville’s novels as a model for how leaderless collectives can generate forms of sovereignty that do not replicate what the Abbé Sieyès called the 'vicious circles' of founding illegitimacy.

Perhaps the most powerful recurrence of Melville’s circular figure occurs in chapter 87 of Moby-Dick, The Grand Armada. It may even be the fullest representation of democracy in all of his work. In that chapter, the Pequod encounters a massive pod of whales, who have sworn 'solemn league and covenant' to protect themselves from whalers. They do so by forming into a vast circle, with a nursery of newborn whales at its centre.

The Pequod encounters a massive pod of whales, who have sworn 'solemn league and covenant' to protect themselves from whalers

As the Pequod attacks the whales at the outer perimeter, Ishmael describes how the giant circle appears to be collapsing on itself under the threat as the outer rings close in on the centre. But soon he sees that this is not a panicked collapse. Instead, the circle is undergoing a purposeful change so that the whales can safely flee.

In short, Melville figures a ruthless democracy of whales – a cetocracy. This democracy acts collectively and decisively while under threat, choosing to transform themselves in order to live rather than to kill.

No.103 in a Loop thread on the science of democracy. Look out for the 🦋 to read more in our series