Recent European elections have revealed that voters are increasingly polarised on environmental protectionism. Christoph Arndt, Daphne Halikiopoulou and Christos Vrakopoulos contend that local opposition to climate change measures is reinforcing a centre-periphery cleavage in Western Europe

What drives attitudes towards specific climate change policies? Who is willing to pay to protect the environment and who is not? We address these questions in a new study that focuses on the important, yet largely overlooked, spatial dimension of environmental protection. Our analysis examines the drivers of (and polarisation around) climate change policies at the regional level.

Climate change is a collective action problem, and can trigger different reactions if perceived as diffuse or more specific

We start by contending that climate change is a collective action problem. It can trigger different reactions if perceived as diffuse or more specific. Accordingly, it is possible that people care about the environment in an abstract way but oppose a particular environmental policy if they see this policy as costly to them personally. Policies which create diffuse gains but concentrated losses have the strongest tendency to generate resistance among those concerned.

Therefore, climate policies may receive broad support from the general population. But they are also likely to receive concentrated opposition from the rural communities where local costs are incurred. Indeed, people may be more likely to mobilise against a policy development in their local area than to be broadly in favour of a climate policy.

Our findings are in line with these theoretical expectations. We provide empirical evidence of a widening centre-periphery divide and highlight its relevance for our understanding of green attitudes. Specifically, we combine European Social Survey (ESS) data with comprehensive data for 186 European regions. This allows us to examine a range of individual and regional-level factors that may trigger opposition to environmental policies. We distinguish between broad environmental concerns and specific climate change policies to directly test whether ‘policy losers’ specifically oppose these measures.

The results show that economic insecurity is a key driver of the reluctance to support (costly) environmental policies. The ‘prosperity hypothesis’ about the relationship between rising standards of living and environmental protectionism applies to the regional level; opposition to climate change policies stems from individuals who incur the concentrated costs of these policies.

Economic insecurity drives reluctance to support (costly) environmental policies, but this effect only applies if climate change measures have concentrated costs

Specifically, at the individual level, our findings support the presence of a centre-periphery divide. Individuals in small towns and rural areas are more likely to oppose climate change measures. In addition, the likelihood of supporting climate change measures increases with income.

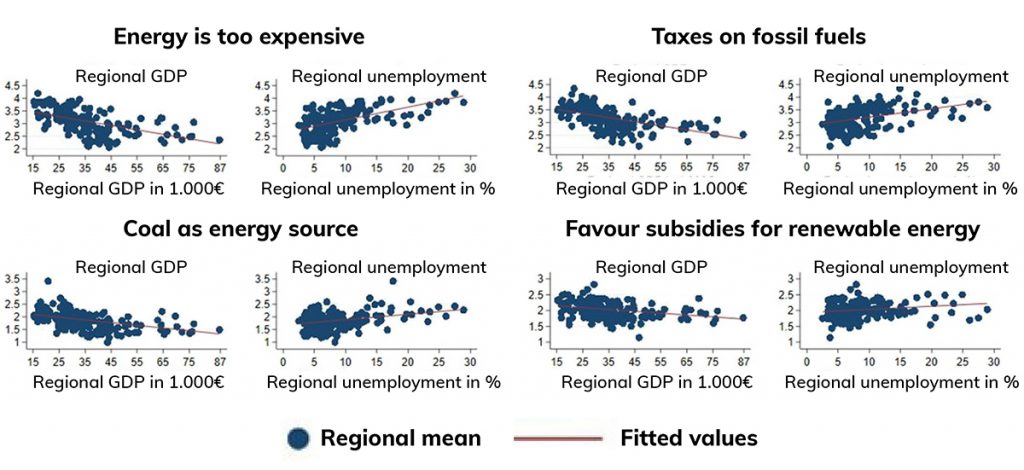

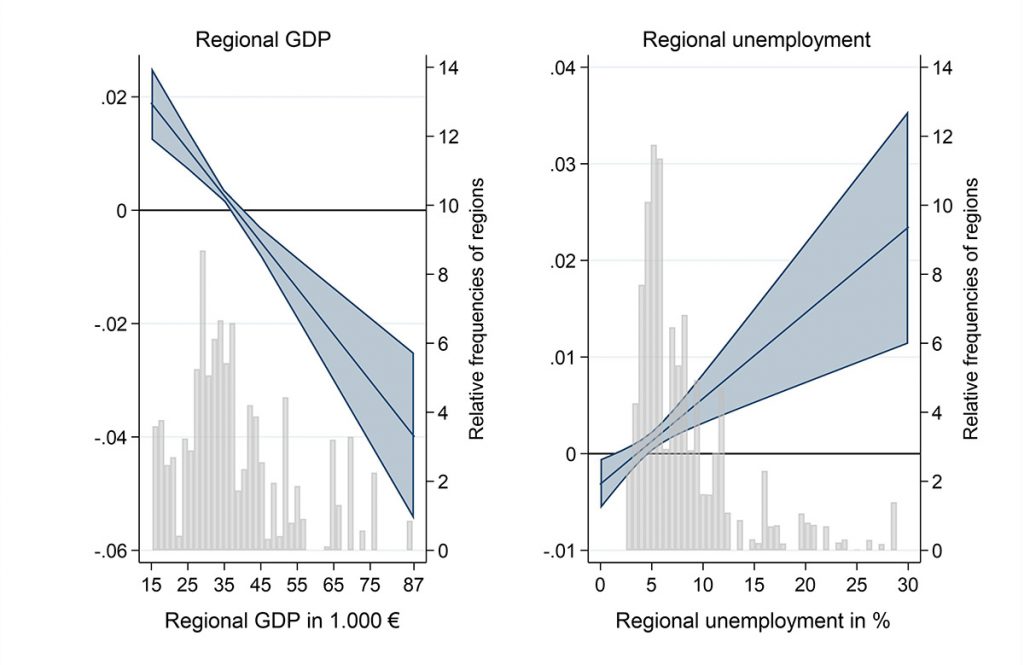

At the regional level, we identify an economic insecurity mechanism behind the lack of willingness to pay for green politics. Residents of poorer regions (Figure 1) are less willing to pay to protect the environment compared to their more well-off counterparts. We can see a similar trend among those with the highest unemployment rates (Figure 1) and coal production (Figure 2).

Note: Higher values on the y-axes denote higher support for a policy or statement.

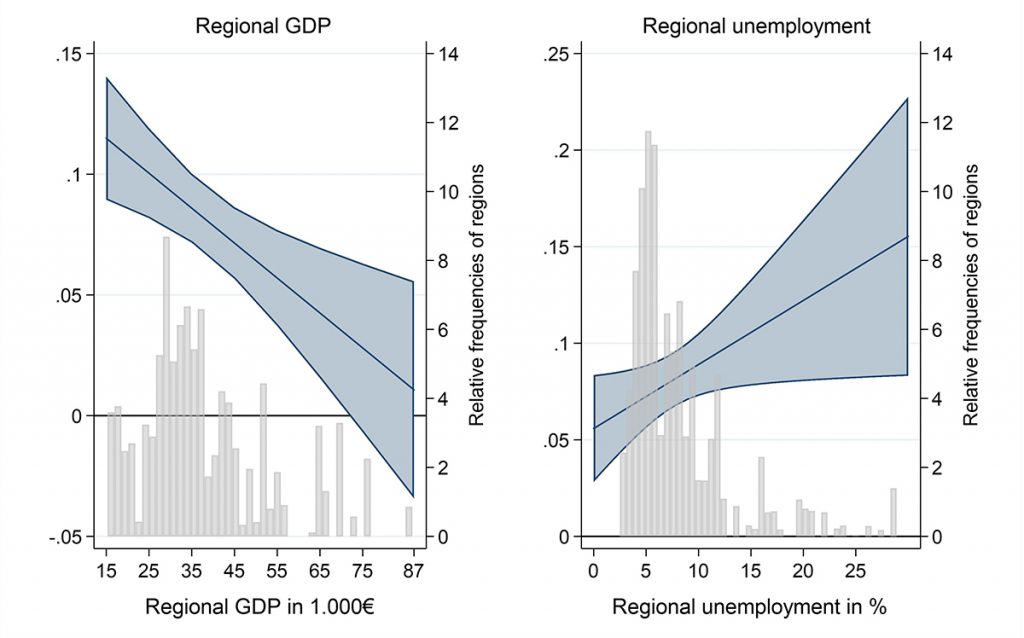

In addition, income moderates attitudinal characteristics. Individuals with egalitarian attitudes who live in poor regions, or regions with higher unemployment rates, are more reluctant to support costly environmental policies (Figure 3).

Last, we demonstrate that the structural components in attitudes towards climate change measures are only existent and virulent if climate change measures have concentrated costs. Therefore, it is a question of whether there are socially defined losers and winners (low-income groups and rural dwellers). If the costs of climate change measures remain diffuse (as for subsidies of renewables), income and residence effects remain weak and insignificant predictors of climate change attitudes.

Our findings are relevant to current debates about the prioritisation of climate change measures in the political agenda. The consequences of local resistance can be detrimental for political stability. Moreover, such resistance can lead to accountability failures, as citizens punish incumbents for controversial costly policies.

Local opposition can divide progressive agendas and even undermine coalition efforts. Debates in Germany between the Greens and the Left Party about increasing fuel prices illustrate this. Opposition can also prevent the implementation of green policies, as the result of the 2021 Swiss referendum illustrates. In turn, climate scepticism may mobilise right-wing populist actors, fuelling the rise of anti-establishment politics.

To be politically successful, ecological policies need to align private and social benefits. The knowledge that resistance to environmental protectionism is likely to be concentrated in specific local communities is an important tool for governments and policymakers.

To succeed, ecological policies must align private and social benefits, addressing potential backlash from local communities who may lose out

If the potential ‘losers’ of these processes trigger backlash against climate change policies at the local level, then emerging centre-periphery divides on climate issues are key to understanding new political alliances. In these, populist right-wing parties increasingly align with the periphery and the countryside, and green parties with the metropolitan centres.

Such developments are already visible in a series of European elections. These have demonstrated a polarisation between two groups. On the one hand, there are the progressive, egalitarian, metropolitan wealthy middle classes concerned about climate change. On the other hand, there are the ‘left behind’ low-income individuals residing in poorer regions who have no incentive to support policies that hurt them financially.

As a result, the rift between right-wing populist and green parties has built up a geographical anchor. Green attitudes matter increasingly for the emergence of societal cleavages, and have significant political implications.